A DNA portrait reveals more than what you look like

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

For most portrait artists, work begins with a sitting or a photograph.

For artist Lynn Fellman, it begins with a cheek swab. "The first thing I do is give you a lab kit. So you do a cheek swab, and it takes the cells out of the inside of your mouth. Then we send that to the lab," explains Fellman.

If you're a woman, the nonprofit genetics lab Fellman uses will send you back information about your ancient family history through your X chromosome, or maternal line.

If you're a man, it reveals your paternal genetic history through your Y chromosome. It tells you when your ancestors first left eastern Africa tens of thousands of years ago, and the journey they made across Europe or Asia.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The family you belong to is called a haplogroup. Artist Lynn Fellman has traced her own genetic ancestry. She's of northern European descent, and belongs to the relatively young Haplogroup H.

"I'm 15,000 years deep ancestry," says Fellman. "What that really means is that my ancestors hung out in the Neolithic age, further down in the Fertile Crescent. We waited for it to warm up, maybe we painted some caves, maybe not - who knows! And when it warmed up we moved up into northern Europe."

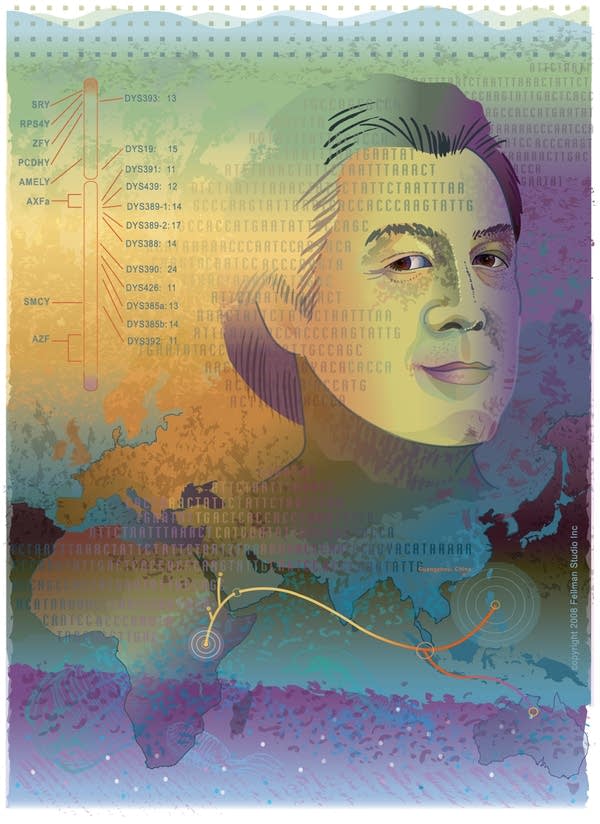

Using her computer, Fellman layers images of maps, DNA sequences, and sometimes even a face, to create a digital portrait of her subject, down to the person's unique genetic sequencing.

It's a complex and colorful image like something you might see illustrating an article in National Geographic.

Fellman recently completed a portrait of Eric Tam. It shows the journey his ancestors made close to 50,000 years ago out of Africa, through the Middle East and into Asia. But Tam says what he finds really fascinating is the way Fellman transforms his history into a vibrant image.

"That's my main interest is to have this beautiful work of art hanging on the wall," says Tam. "In terms of tracing my ancestors, that to me is almost secondary."

The technology Fellman uses has only become available in the past couple of years.

In addition to her portraits, she also makes silk scarves and ties with images of DNA helixes, and words like "gene regulatory regions" and "messenger RNAs" sprinkled across them.

She's had good luck promoting her work at scientific conferences. Fellman says selling to geneticists, however, can be tough.

"They would say fun things like, 'I love this scarf, it's a beautiful color, it's just what I need, but I want one with the chromosomes in it,'" says Fellman.

An exhibition of Fellman's work at the Women's Club in Minneapolis and runs through Feb. 24.

Like many of Fellman's customers, Philip Mednick has a science background but is also interested in art. He says what Fellman is doing is rare.

"I'm a scientist by trade, and here's something very artful, an interpretation of science through art," says Mednick.

Fellman says it's her dream to someday work with scientists to help them communicate their ideas, using art as a tool. Fellman says many of the geneticists she meets caution her that while her portraits are beautiful, what we know about genetics is constantly changing.

"This is what's exciting," says Fellman. "It will change. Basic understandings will remain the same -- it's the details that we're filling in. The nuances will change, and we'll fill in the picture."

The genetic information Fellman uses doesn't reveal recent history, the way family genealogy does. Due to increased migration and mixing of families, its accuracy dwindles starting around 10,000 years ago.

But Fellman looks forward to a day when we'll know enough about our genetic history, and our written history, to be able to close the gap between the two.