One man's fight for citizenship

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Juan Alameda spent the past year in the Ramsey County Jail, trying to prove he shouldn't be deported to Mexico.

Except for the work of a volunteer legal team, he could be on the way back to a country he hasn't seen in nearly two decades, away from his children.

Born in Mexico in 1962, Alameda has lived in the United States since 1991, when his father, a U.S. citizen from Texas, sponsored him so he could legally enter the country and obtain permission to work here.

His mother, a native of Mexico, died in Willmar, Minn., several years ago. Though he was born abroad, as the son of a U.S. citizen Alameda was eligible for U.S. citizenship. But the burden was on him to prove it.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

If he couldn't, he would join the dozens of people federal authorities deport to Mexico every Wednesday at noon, when a flight leaves the Minneapolis-St. Paul airport bound for the Mexican border. Federal authorities repatriated more than 6,000 people from the Upper Midwest last year, the vast majority to Mexico.

Most of them have no legal way to stay in the country, or little or no wherewithal to press their case. Alameda did.

TROUBLES IN MINNESOTA

Alameda followed his brother to Minnesota about 10 years ago. He had a green card and worked in poultry processing plants in Willmar and St. James.

He and his girlfriend had two daughters together, 12-year-old Selena, named for the Tejano music superstar who died in 1995, and Karla, 7. The girls' names are tattooed in cursive on his neck. For years, Alameda didn't see them.

Authorities charged him with beating up a man he suspected was dating his girlfriend. Then Alameda was jailed on a drug charge.

He served 35 months in prison for those two crimes. Then Immigration and Customs Enforcement tried to deport him. The agency's top priority is deporting criminals.

When Alameda arrived at detention court in Bloomington last February, volunteer attorneys and law students with the Detention Project screened his case. Overseeing the legal triage that day was Paula Duthoy, who runs the immigration clinic at William Mitchell College of Law.

When the lawyers interviewed Alameda they asked if he had a green card. When he said "yes," that led to more questions -- and opened a potential path to freedom.

"How did you get your green card? How did you get your residence?" the law students asked. "Well, my dad's a U.S. citizen," Alameda replied.

"Oh! Well then we'd better look," recalled Duthoy. "Are you a citizen?"

The Detention Project claims to rescue U.S. citizens from deportation proceedings each year. Duthoy remembers the day she found two citizens on their way to being deported. She kept them in the United States.

"I would say that it's quite rare," said Tim Counts, a spokesman for U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. "What is not rare is people who are not U.S. citizens who falsely claim to be U.S. citizens. In fact, that's something that happens every day across the country."

The federal government spent nearly $30,000 to keep Alameda in custody while he fought his citizenship case. He was a mandatory detainee because of his criminal record.

PIECING TOGETHER AN OLD MAN'S LIFE IN TEXAS

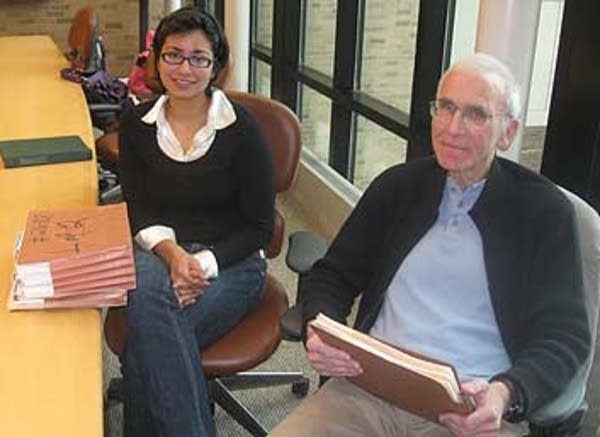

From behind bars, Alameda had to furnish proof that he met the criteria for "birth abroad" citizenship. With the help of Roger Junnila, a volunteer attorney with the Detention Project, and William Mitchell law students, Alameda proved his father is a citizen of the United States, that his parents were married, and that he was born in Mexico.

Citizenship would hinge on meeting a fourth requirement: That the elder Alameda, born in 1930, lived in the United States for 10 years before his son was born in 1962.

Five of those years must have been after his father turned 14. Today the requirement is five years total.

Sam Alameda is certain he's been here for decades.

"Most of my life I lived here in the United States," Alameda, 79, said by phone from his home in Beaumont, Texas.

Sam Alameda has a fourth grade education. He always worked in restaurants that paid him in cash. He never held a driver's license or owned a car. Because he lived with his aunt in Texas as a young man, he didn't have rent receipts.

Junnila describes the elder Alameda's existence as "sub rosa." He left no paper trail. And there was another problem.

Even if he had hung onto some scrap of paper placing him in the United States during the 1930s, '40s or '50s, hurricanes Rita and Ike swept through the Texas gulf region, flooding his home twice.

"In my living room it was raining," Sam Alameda said. "It took all the papers. I don't have nothing like that."

Alameda couldn't help his son.

So Junnila and the William Mitchell law students contacted every state and federal agency they could think of to piece together Sam Alameda's early life in Texas. The only public document linking him to Texas was a selective service registration for 1956.

Junnila's folder on the Alameda case was thick with dead-ends.

"In desperation, we started having Juan write letters to his father and to his relatives saying, 'Would someone please help my dad find information?'" said Junnila. "Juan would sit in jail and write these letters, and I'd mail them out to his siblings and his father and everybody else."

Nobody wrote back.

Juan Alameda's pro bono legal team finally had to rely on affidavits from people who knew Sam Alameda back in the decades before his son was born, and could vouch for him living in Texas. The team members crossed their fingers and waited. They'd pursue the case as long as Alameda was willing to stick it out in jail.

Last week the lawyers got a call from Alameda, who told them he would receive his citizenship and be released. Federal immigration authorities say they can't comment on the case because of privacy rules.

WELCOME TO AMERICA

A few days later, Alameda stood in a suit and tie outside the Citizenship and Immigration office in Bloomington, holding his signed certificate of citizenship.

"I'm happy," he said.

Alameda thanked God for giving him citizenship.

Paula Duthoy, the William Mitchell attorney who first flagged his case, spent that morning helping new detainees sort out their legal options. None of them were U.S. citizens, and most chose to be sent back to Mexico, the Philippines, Senegal and other countries.

When Duthoy congratulated Alameda and eyed his certificate, she noticed something.

"They wouldn't let you change your clothes when they took your picture?" she asked Alameda.

"No," he replied.

Alameda's permanent document of citizenship shows him in his orange jail uniform -- a reminder of the price he paid to prove it.