Central Corridor: In the shadow of Rondo

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Before Interstate 94 plowed through St. Paul's Rondo neighborhood, the Rev. George Davis tried his best to stay in his home.

When Davis refused to move, authorities forcibly removed him. Police arrived at the preacher's house on Sept. 28, 1956. They came bearing axes and sledgehammers, a sight that caused his 13-year-old grandson to cry.

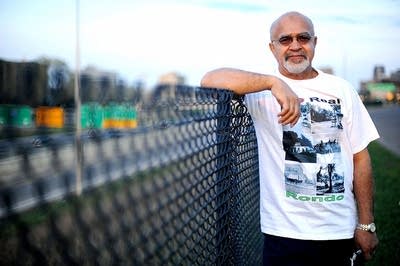

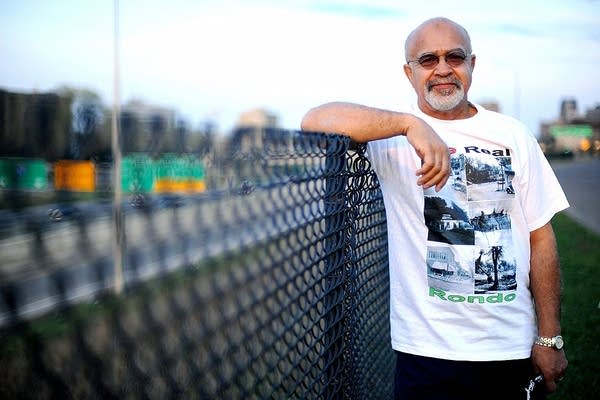

"They were knocking holes in the walls, breaking the windows, tearing up the plumbing -- just to make sure he didn't try to move back in there," recalled Nathaniel Khaliq, now 66, who is Davis' grandson. "I was crying because it looked like something bad happened."

Like an unhealed wound, such memories are still raw for Khaliq, president of the St. Paul branch of the NAACP. He's determined to ensure those who remain in Rondo are heard on the next large-scale transportation project.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

For him, and many others from the Rondo community, this is the legacy of I-94: The government moved about 650 families in all, and tore the neighborhood in half. The new freeway wiped out homes and businesses, as well as some of the equity that longtime residents built in their homes and would have passed onto their children.

A LACK OF TRUST

Some African-Americans in St. Paul see parallels between the interstate project and a light-rail line planned for University Avenue, about five blocks north of the freeway.

The third in a four-part series examining the Central Corridor light rail project in St. Paul.

Worried about the light-rail project's potential effect on the neighborhood, the NAACP, Rondo residents and businesses are suing local project planners and the Federal Transit Administration. They allege the Metropolitan Council failed to fully analyze the project's effects on poor people and minorities.

The plaintiffs also include Debbie Montgomery, the first black woman elected to the City Council; Arnellia's, a popular bar on University Avenue; and Pilgrim Baptist Church, one of the oldest African-American churches in Minnesota.

[image]

They're worried that the transit project will force up property values and drive out lower- and middle-income residents. They also think it would make it more difficult for people without cars.

That's because the Route 16 bus, which stops at about every block on University Avenue, would likely run less frequently once light rail is in service. The Met Council says plans to reduce the Route 16 to run every 20 minutes instead of every 10 minutes during rush hour are not final.

Khaliq said he doesn't trust light-rail planners, because they haven't listened to the community's concerns about the route selection.

"We weren't at the table at the inception of this project," Khaliq said. "Some other folks made the decision about where the project would be located. We started off on the wrong foot."

At this point, Khaliq knows the light-rail route isn't going to change. Picking a different path now would likely delay the project by at least a couple of years, because it would require extensive study.

Khaliq can only hope for concessions. He's asking for tax abatement for residents, financial help for businesses, and affordable housing laws that would keep community members from having to uproot themselves again.

Supporters of light rail say those requests are beyond the scope of the Metropolitan Council, and are better left to the city of St. Paul to deal with. City officials say they're crafting affordable housing strategies, parking solutions and plans to help businesses.

EXTRA STOPS

One wish made by a large cross-section of St. Paul community groups is coming true. Residents demanded three extra stations along the light-rail line on University Avenue to better serve people who live and work in the corridor.

The Metropolitan Council included the stations at Hamline Avenue, Victoria Street and Western Avenue, after an outcry from community members and local officials persuaded a key Washington bureaucrat to agree with them.

"Probably no project more than the Central Corridor convinced us to make this change," said Peter Rogoff, administrator of the Federal Transit Administration.

In January, the transit administration, under Rogoff, announced it would evaluate transit projects differently than the Bush administration. The agency relaxed a rigid funding formula that valued a project's cost-effectiveness above all other criteria.

Rogoff said the old federal rules led to some "silly" decisions for the Central Corridor planners, who spaced stops as far as a mile apart to save money. Those missing stations were in neighborhoods home to poor people and minorities who need transit the most.

He also said that earlier plans in St. Paul did not address transportation from a civil rights perspective.

Rogoff's agency now considers a number of livability factors, including economic development and congestion relief.

While Rogoff's attention to social equity worked to benefit the Central Corridor line, it killed a rail project in California. In Oakland, the Bay Area Rapid Transit lost $70 million in stimulus money to pay for a connector to the airport.

In that case, federal transit officials found the local transit agency ignored civil rights laws that require agencies to study whether low-income and minority communities would receive a fair share of the project's benefits.

Rogoff said his agency will make sure that public money for transit is spent fairly and equitably.

"There is no question that this administration is going to look at civil rights compliance on the part of transit agencies," he said. "I think it's fair to say there wasn't a lot of attention paid to it in recent years."

Rogoff declined to discuss the merits of the Rondo lawsuit or a pair of civil-rights complaints filed by St. Paul's African-American and Asian communities. But he said he's particularly fond of the Central Corridor project, now that the extra stops will serve those neighborhoods.

A DIFFERENT VIEW

In St. Paul, you'll never hear Peter Bell talk about the Central Corridor in the context of civil rights.

"I don't know if I buy the civil-rights argument," said Bell, chairman of the powerful Metropolitan Council, a regional planning agency that is building the light-rail line.

"There are many disparities that exist in this country based on race and income. You have health care disparities, you have disparities in the criminal justice system, you have educational disparities," Bell said. "Let me tell you one place you don't have disparities: That's transit. Low-income minority people across the country have more transit than upper-income non-minority individuals. That's a fact."

Bell said he long supported building the three additional stations along the light-rail line. Before the federal rule change, the Met Council committed to building the foundations for the stops, so it could finish them when money became available.

But Bell said his hands were tied by the federal cost-effectiveness index, and he had to play by those rules.

A 58-year-old fiscal conservative appointed by Republican Gov. Tim Pawlenty, Bell has become the public face leading the charge for light-rail on University Avenue, often in the name of progress.

It may surprise some to learn that Bell, who is African-American, also grew up in the Rondo neighborhood -- and that he shares a history with Nathaniel Khaliq. The government also took away Bell's childhood home in the late 1950s for the interstate.

Bell recalls the experience as unsettling, but not on the scale as others remember it.

"I was traumatized, because I was a 6-year-old kid taken away from his best friend," Bell said. "Marvin Mitchell was this kid's name. And we were just great buddies, and I had to move away from my best friend."

Bell said light rail will bring investment to an area crying for rebirth. He said the Central Corridor project is not another Rondo.

"Its power to revitalize that corridor is beyond serious debate," he said. "[To] the people who question that, I say, 'OK, what's your answer to revitalizing University Avenue?' Not enough people are saying, 'If not that, then what?'"

The Rondo analogy falls short on many levels. Putting a train down the middle of University Avenue won't require digging up a quarter-mile trench that was needed for I-94. No homes are being taken this time. And compared with the interstate project 50 years ago, the government is being much more transparent, even if people aren't getting exactly what they want.

Still, the concerns of civil rights aren't limited to those whose families lost their homes to the freeway. Many of the business owners along the east end of University Avenue weren't even around, and set up shop when no one wanted to be here.

RESIGNED BUT WORRIED

Others who are worried include Alex Pham, who owns a restaurant on University Avenue. His soup shop, Pho Ca-Dao, has a wall of mirrors and a pot of silk flowers that give it a 1970s vibe. Young families and the Capitol crowd alike come here for hot steaming bowls of Vietnamese beef broth.

Pham took a gamble 18 years ago when he opened his restaurant in the Frogtown neighborhood. Back then, he says, he ran into prostitutes and dope dealers, and put his own life at risk.

"We got beat, we got robbed. But we stay," he said. "We determined if we try hard in this area, we can get it going, and we can turn the area around. And we succeeded."

Nowadays, many of the businesses are struggling because of the economic downturn. And it's uncertain whether they'll be around when the trains roll by.

"They're barely above water," Pham said. "If light rail come in, we'll definitely be under. How we'll deal with it? We don't know."

The project would cut out 85 percent of the avenue's street parking. Asian business owners, who filed a civil-rights complaint with the Federal Transit Administration over the project, believe they will be disproportionately affected by the parking crunch -- and the overall dust, debris and commotion while the line is being built.

Some business owners are trying to get ahead of the trains by working with business development groups on their marketing plans. The Asian Economic Development Association hopes to re-brand this stretch of University Avenue "Little Mekong," in deference to the river that ties so many of the various ethnic entrepreneurs hailing from Southeast Asia.

But Pham would rather not see the trains come at all. He thinks the construction will destroy everything he has worked for.

St. Paul Mayor Chris Coleman acknowledges the line will bring change, not all of it welcome. But a far worse alternative, he said, is neglect.

Coleman recounts his work as a community organizer in Frogtown, one of the neighborhoods along the light-rail route.

"We were demanding this kind of investment; we were demanding some attention," Coleman said. "We need to be prepared for change, but let's make sure that change benefits the people who are already there."

While transit does spur economic development, most experts say the changes typically follow already existing patterns.

"What has tended to happen is already strong markets have gotten stronger. And in places where there hasn't been as much development, they aren't as completely transformed," said Sam Zimbabwe, director of the Center for Transit-Oriented Development in Washington D.C. "Transit alone isn't creating a market for development."

For example, the project might continue to spark development along the western edge of University Avenue in St. Paul. There are already clusters of new condos, artist lofts and a gourmet cupcake bakery.

But some of the more challenged neighborhoods, such as Frogtown, may continue to struggle without additional support, Zimbabwe said.

For all the talk about trying to minimize the impact of light rail, St. Paul City Council Member Melvin Carter III wants to do just the opposite.

"A billion-dollar investment needs to have a billion-dollar impact," Carter said.

Carter and his mother, Ramsey County Commissioner Toni Carter, are big supporters of the Central Corridor line. Melvin Carter and other local officials fought for the three extra stops, and he still sees big challenges ahead with the project.

Carter's main goal is to make sure longtime residents and businesses are first in line for new jobs and housing that the transit service will bring.

The 31-year-old Carter, a former track star at Central High School, wasn't alive when the interstate tore apart Rondo. But he grew up hearing stories about the neighborhood. His great-grandfather, Mym Carter, led a jazz string band in on a horse-drawn buggy down Rondo Avenue. And Carter's grandfather owned a handful of commercial buildings that the councilman says he probably would have inherited.

Carter's own father, who lost his childhood home to the freeway project, often shared his memories of Rondo on car trips around St. Paul with his kids.

"Growing up, we'd ride I-94, and just before the Dale Street bridge, he'd say, 'You're in my bedroom -- now!'" Carter recalled. "And for those folks who lived that, and even for someone like me, who grew up hearing the stories of Rondo far before I ever knew what the letters LRT stood for, and grew up with a gut, gut feeling about how horrible a tragedy Rondo was, I think it's understandable somebody can look at [light rail] and say, 'No thanks.'"

That doesn't mean residents should resist light rail, Carter said. But there is a lesson to be learned from Rondo:

"It happened so long ago, but we're still in the shadow of Rondo," he said. "That's exactly what makes it so important that we choose our steps very carefully now."

Light rail can change the community as much as I-94 did, Carter said. But this time, he hopes it will correct the wrongs of history.