Cops find social media an effective tool to catch criminals

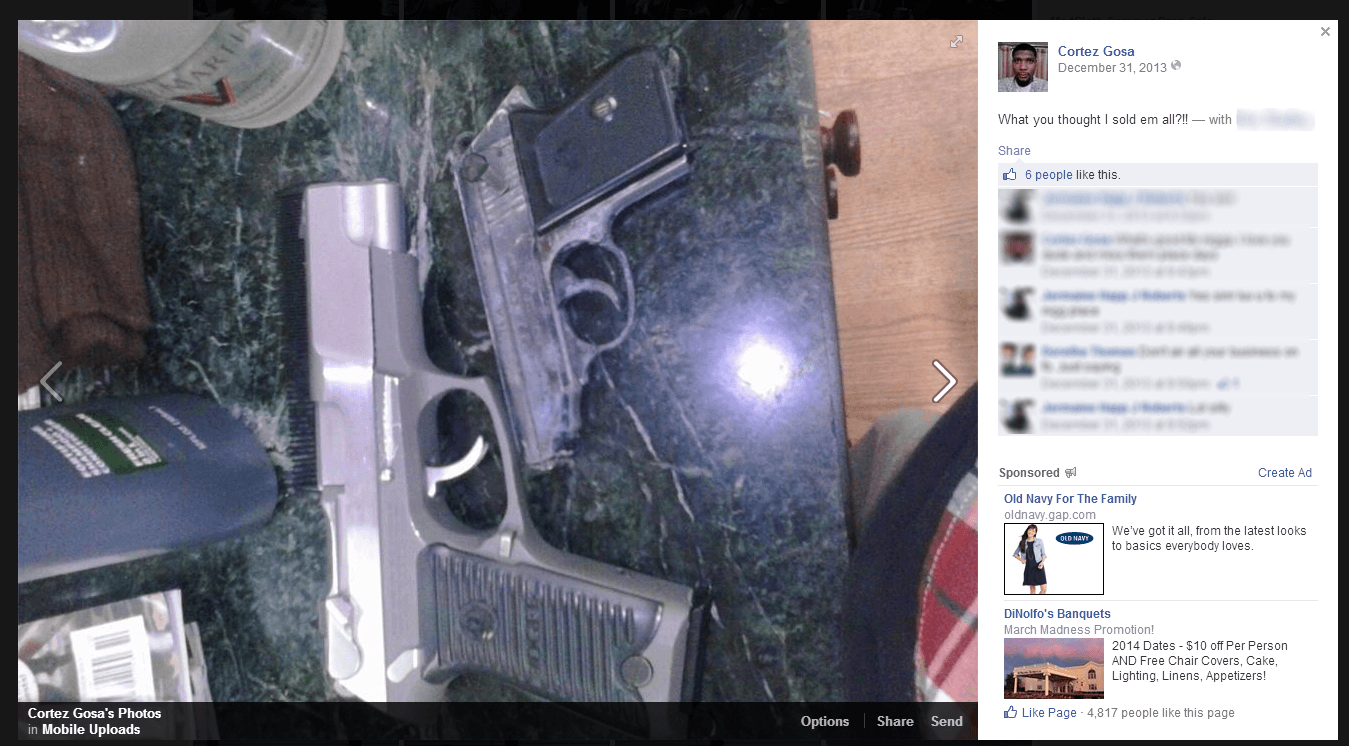

Cortez Gosa posted photos of guns he had on Facebook, saying "What you thought I sold em all?!!" Gosa's Facebook photos were noted in the criminal complaint.

Screen grab via Facebook

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.