MN near bottom in on-time graduation for students of color

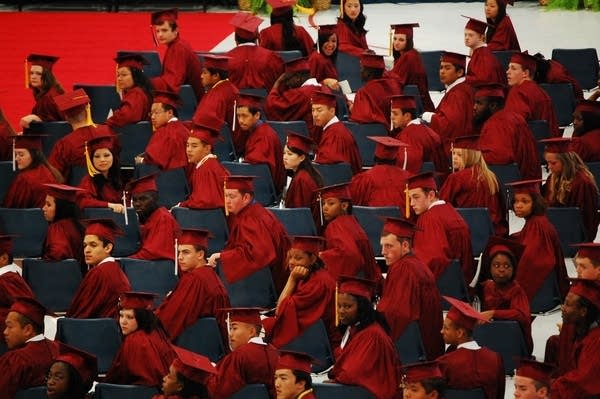

The class of 2010 from St. Paul's Johnson High School at graduation.

Tim Post | MPR News 2010

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.