Cheetos, canned foods, deli meat: How the U.S. Army shapes our diet

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Many of the foods that we chow down on every day were invented not for us, but for soldiers.

Energy bars, canned goods, deli meats — all have military origins. Same goes for ready-to-eat guacamole and goldfish crackers.

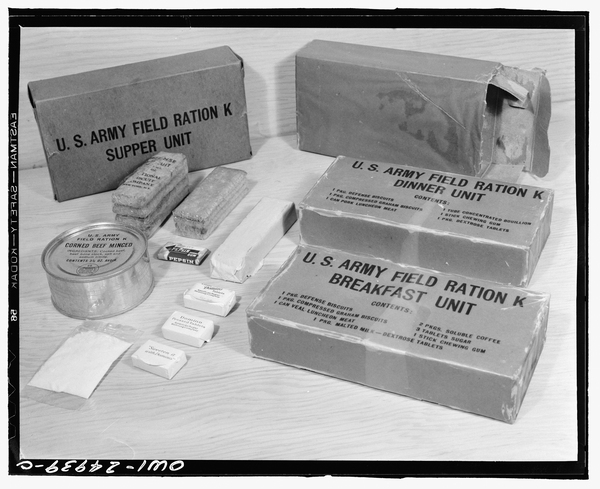

According to the new book, Combat-Ready Kitchen: How The U.S. Military Shapes The Way You Eat, many of the packaged, processed foods we find in today's supermarkets started out as science experiments in an Army laboratory. The foodstuffs themselves, or the processes that went into making them, were originally intended to serve as combat rations for soldiers out in the battlefield.

Indeed, military needs have driven food-preservation experiments for centuries.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Canning, or bottling, was invented at the turn of the 19th century, when the French army offered a reward for someone who could invent a way to keep foods longer. (Napoleon's men, as The Salt has reported, were often ill-provisioned.) But as author Anastacia Marx de Salcedo writes, the U.S. Army has taken this research to a whole other level. She says many food innovations trace back to the Natick Soldier Systems Center, a U.S. Army research complex in Natick, Mass. The federal laboratory investigates how to make soldiers' rations taste good and last longer. She says its initiatives have led to the processed cheese that's now found in goldfish crackers and Cheetos. The center is also behind longer-lasting loaves of bread and the energy bar, which was originally created to give worn-out soldiers a boost, she says.

So what does that mean for us civilians? The Salt chatted with Marx de Salcedo to learn more. Here are highlights from the conversation.

How does Army research lead to products on our supermarket shelves?

Most people don't realize that the military has a policy to get the science that it uses for rations into the public's food. The reason is military preparedness. This dates back to a policy that was made after World War II, which is designed to make sure both the military and its supporters can be ready at a moment's notice to convert over to producing rations or to create consumer products that they might be substituted in their stead. The key point here is that companies don't generally invest in basic and applied food science. What the Army is looking at is the big questions in food science. There are not many other places interested or able to do the research, so the Army guides the direction of food science.

What's one of the most surprising foods the U.S. military helped create?

There's something called high-pressure processing. It's not so much a surprise, but a wonderful example of how the Army organizes itself. They pick a topic, decide to pursue it and organize a team to solve the problem. The issue was finding new ways to preserve food, and HPP came out of that.

HPP is the application of a tremendous amount of pressure to food. The example I usually give is: Picture 20 minivans on a single penny. [The force applied] is that extreme, and what that does is it kills any bacteria that may be in the food.

The important thing here is that along the way, companies took the technique and began applying it to their own products. Many of the single-serving fresh juices use this [method] — it's a way to sterilize juice without losing the flavor. Ready-to-eat guacamole uses HPP, and so do many salsas. The big one is Hormel. In the mid-2000s, it applied the technique to deli meats. This whole line of deli meats now says no preservatives on the label, and that probably means it was produced with HPP.

You mention in your book that America is feeding its children like they're special ops. How so?

I literally realized that everything in my kids' lunchboxes had military origins or influence — the bread, the sandwich meat, juice pouches, cheesy crackers, goldfish and energy bars. Even if we look at fresh items like grapes and carrots, the Army was involved in developing packaging for fruits and vegetables. In a larger sense, I estimate that 50 percent of items in today's markets were influenced by the military.

What's the military working on now that we may see in the future in supermarkets?

One thing they're working on is shelf-stable pizza. What I mean by that is the vision of the future is really a place where we don't need refrigeration. This pizza could just be left in your pantry for a long time, like as long as you leave [canned goods].

They're also working on shelf-stable sandwiches, wraps and bagels. In fact, it seems like the military is moving to a system where they want to reduce or eliminate regular hot meals like breakfast, lunch and dinners. Instead, they'd just provide day-long grazing options for soldiers. I think we could definitely see this affect the consumer market in the future. Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.