What food companies learn from U of M chew-bot

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A number of big food companies are trying to change up their product formulations these days to include healthier ingredients. Earlier this month, Mars Inc. joined the ranks of companies cutting artificial coloring from candies like M&Ms and Skittles.

But changing a product can be risky. It might end up tasting less tasty or crispy than the original one.

"Sugar doesn't just make a product sweet and salt doesn't just make it salty," said Ralph DeLong, a Professor at the University of Minnesota's School of Dentistry. "They also have chemical interactions with the other things that affect the texture of the food."

Some major food companies, which didn't want to be named, are now finding ways to assess how product reformulations affect things like crispiness, thanks to a robot DeLong helped build.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

DeLong said the original robot, invented 30 years ago, was designed for the purpose of testing dental restoration materials. The super-chewer robot could put wear and tear on them a lot faster than humans could and cost a lot less to employ.

"For a material that you want to test for five years, in one week you have the result," he said.

The latest version of the robot can give feedback on what it's chewing.

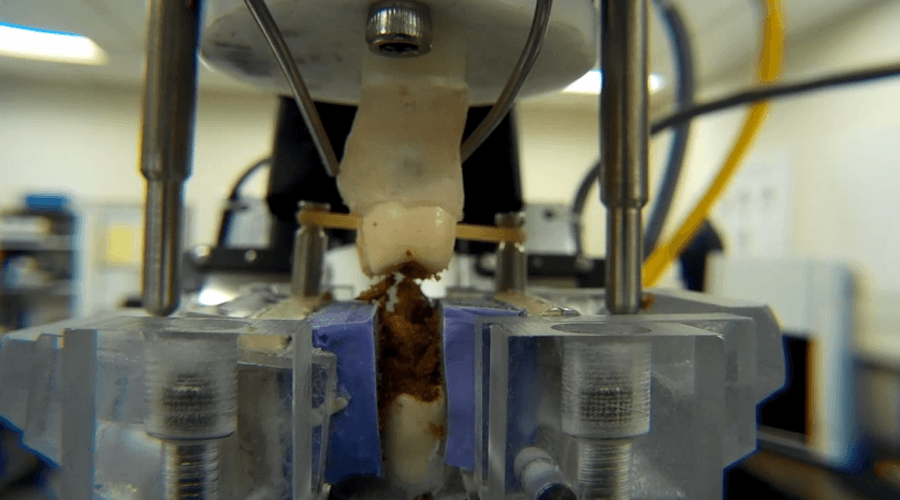

On a recent morning, DeLong and his colleagues fed the robot a piece of puffed cereal. As the robot chewed, its three bottom teeth moved up and down and to the right and the left, while its top three teeth stayed anchored to a base.

Meanwhile, a computer hooked up to the robot registered the audio frequencies emitted by the crunching. Food companies can study the different frequencies emitted when the robot chews. That can be the basis of a comparison between the crispiness of an already successful product on the market and its "healthier" reformulation.

According to researchers at the University of Minnesota's School of Dentistry, the audio frequencies generated when a food product is chewed reflect its crispiness. These are the frequencies generated by a robotic mouth chewing a piece of cereal. "We believe that ultimately crispiness can be quantified by things like the frequency content coming out from those sounds, those crispy sounds," said Alex Fok, director of the Minnesota Dental Research Center for Biomaterials and Biochemics at the University of Minnesota.

Another machine at the Dentistry School provides three-dimensional X-rays of the internal structure of cereal to show how porous its walls are, which Fok said is another factor in crispiness.

And the Dentistry school team is working to capture the vapors emitted when the mechanical mouth chews, which can provide information about a product's tastiness.

Food marketing expert John Stanton said the robotic mouth is just one example of how food companies are trying to make texture and taste more scientific.

"Trying to break it down into its individual pieces, what really affects taste, is what people are working on," he said. "They're using not only physiological models but they also have more sophisticated statistical models."

But apparently there's only some accounting for taste.

Stanton said unlike robots, people come with all sorts of messy biases about food, which could stem from whether the packaging or advertising appeal to them, or whether they were forced to eat a particular food when they were kids.

He said food companies still have to consider those biases at some point in developing products.

This story originally appeared on Marketplace.org.