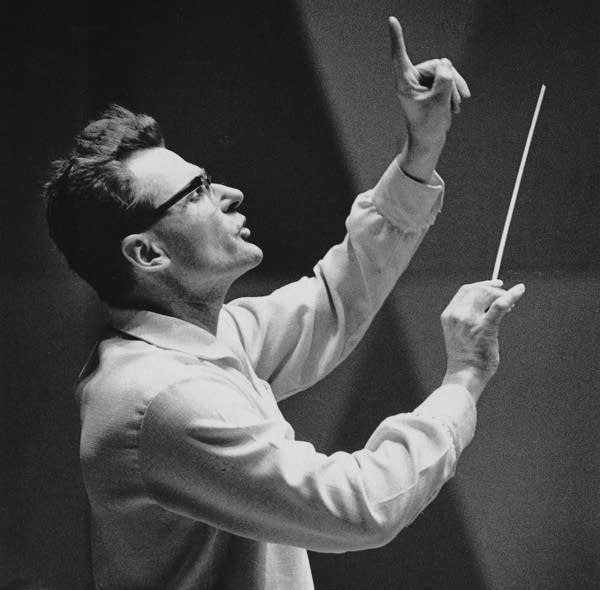

Stanislaw Skrowaczewski, Minnesota Orchestra's conductor laureate, dies at 93

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Minnesota Orchestra Conductor Laureate Stanislaw Skrowaczewski has died. He was 93.

Skrowaczewski came to Minnesota decades ago to lead what was then the Minneapolis Symphony Orchestra, and he never left. He changed the face of classical music in Minnesota, and remained a towering presence in the classical music world until the end.

He had fallen in love with music while very young, as a boy in Poland.

"When I was 4 I started to play piano myself," he told MPR in 1997. "Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven. Sonatas, sonatinas, chamber music."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The music touched him in a way probably few of us can understand. He told a story of something that happened to him in the street one day:

"Being 7, I heard something on the street, in an open window, in the summer, from the radio, that completely impressed me so much that I became very sick, physically sick," he recalled. "For three days, with a high temperature. It was Bruckner's Seventh Adagio."

That bolt from the blue began a lifelong love of the composer's work. Skrowaczewski also began composing his own music at that early age. He became well known as a performer, and eventually planned a career as a concert pianist.

That dream ended during World War II, when a bomb sent a wall crashing down on one of his hands.

He turned instead to conducting, which led him to the Warsaw National Orchestra, then to Cleveland, and finally to Minnesota.

In 1960, he took over as music director of the Minneapolis Symphony, a job he held until 1979, when he became the Minnesota Orchestra's conductor laureate.

He conducted the orchestra at least once a year from then on. He also led independent concerts by the orchestra's musicians during the lockout that ended three years ago, and conducted the first two concerts after the contract settlement.

Skrowaczewski championed new music, and it was he who declared the acoustics of Northrop Auditorium, where the Minneapolis Symphony had played for decades, unacceptable. When asked how they could be improved, he had a one-word answer: "Dynamite."

The years-long drive to build and open Orchestra Hall was one highlight of his tenure in Minnesota.

In 1979, he told MPR that it was shock at first to play in the new hall because it sounded so much better.

"The Northrop was only loud and soft," he said. "When it was too soft, no one could hear at all, and when it was loud, what you hear there was only brass and percussions, no strings. In this hall we can have a very fine texture and performances."

Critics welcomed the improvement in the hall and the resulting improvement in the orchestra, too.

The symphony also was renamed the Minnesota Orchestra while Skrowaczewski was at the helm, although he later said that was a board decision, and he was not consulted.

Lea Foli, concertmaster in the late 1970s, said he believed Scrowaczewski knew 20 or 30 symphonies by heart.

"I can't think of another practicing conductor that has a bigger repertoire or greater depth of understanding of what he is doing," Foli said.

When he finally stepped down after 19 years as music director, Skrowaczewski was seen by some as the last of the breed of conductors who led their orchestras for decades. He became the Minnesota Orchestra's conductor laureate, and appeared with the orchestra at least once a year.

After stepping down as music director in Minnesota, he followed a hectic international schedule, conducting all over the world. He was particularly popular in Japan, where fans celebrated his 90th birthday by inviting him to conduct a series of concerts.

"Composing is the heart of who he is, but he spent a lot more time conducting," Skrowaczewski biographer Fred Harris said. "That insight into music by being both a conductor and a composer makes him special."

Three years ago, a German label released a 28-CD collection of Skrowaczewski recordings, including performances of Beethoven, Bruckner, Schumann, Bartok and Berlioz, as well as his own compositions. The set shows the remarkable scope of Skrowaczewski's work, said Harris, who spent more than a decade writing the conductor's biography, "Seeking the Infinite."

In his later years, Skrowaczewski often looked frail as he walked on stage, but said when he stood on the podium he felt rejuvenated, lifted by the music he loved so much. In 2014, at age 90, he said people just kept asking him to come back.

"And they realize that any moment I can just say, 'I have to stop, and this is it,'" he said. "And if it goes well, why not?"

Skrowaczewski played his last concert with the Minnesota Orchestra in October. The program included his beloved Bruckner.

Correction (Feb. 21, 2017): An earlier version of this story incorrectly spelled Lea Foli's name.