From the archive: After the Vietnam War, refugees struggled for survival

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Throughout 2017, Minnesota Public Radio will celebrate 50 years on the air by sharing highlights from our archives, connecting Minnesota's past to its present. | This documentary by MPR's Greg Barron originally aired in 1979. Narrated by Barron and Bob Aronson, it described the severity of the humanitarian crisis in refugee camps on the Thai-Cambodia border.

MPR marks 50 years

• More stories from the archives

• Join the celebration, tell us your story

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

In 1975 U.S troops pulled out of Vietnam, but the conflicts in Southeast Asia continued without them, creating a wave of refugees, many of which would settle in Minnesota.

The journey to get here was not an easy one, and often included a long stay in a refugee camp.

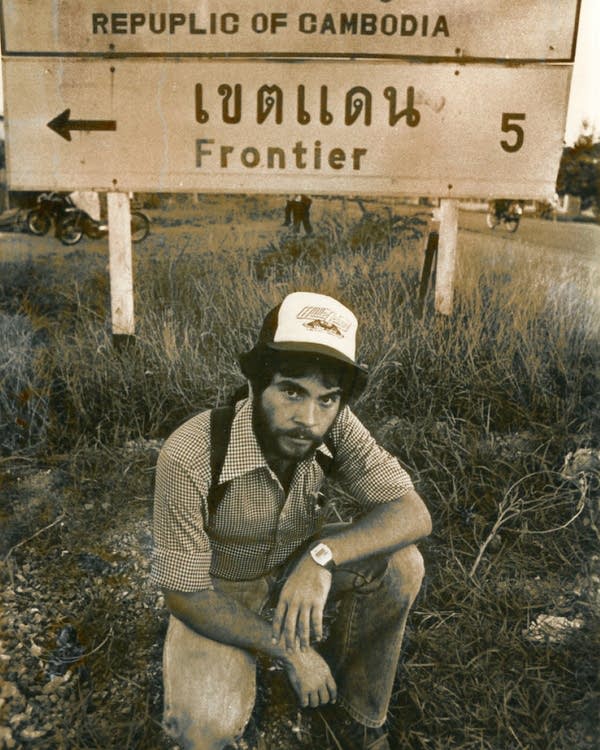

In 1979, MPR reporter Greg Barron traveled to the area along the Thai-Cambodian border and visited several of these camps where hundreds of thousands of people were living. He produced a documentary on what he saw, titled "Trampled Grass."

On the border

That year, scores of Cambodian refugees were still living on the Thai-Cambodian border in an attempt to escape the violence between Khmer Rouge guerrillas and Vietnamese troops.

In order for journalists to travel to that border from Bangkok, a myriad of bureaucratic hoops had to be jumped through before receiving clearance, including a formal request from the U.S. Embassy.

Once there, frequent shellings closed certain areas, and even entire refugee camps to journalists — in part for safety, and in part to control media reports. And if getting there was this difficult, living there had to be a nightmare, Barron reported.

The camps

The first camp Barron visited had over 1,000 tents, with six to eight people per tent — each five by five feet at the largest, Barron said.

Rations were minimal, but at the time of Baron's visit, consistent — with food stations opening up three times a day. The lines were crowded but orderly; soldiers dyed each refugee's fingernails to mark who had already received food.

A ballad of coughs emitted from the crowd, respiratory diseases had spread to even the healthiest refugees, Barron reported. Pneumonia, malaria and malnutrition topped the list of health concerns at the camps and thousands of patients visited the medical tents each day. Children were some of the hardest hit — many suffered from malaria, worms and severe anemia.

A woman working in one of the medical tents said things at the camp, which was now in its third week of operation, were much worse at the beginning, with piles of dead bodies greeting them as they entered the camp each day. Progress had been made, but people were still dying.

Another refugee camp, located near the Thailand village of Bang Nong Samet, was a medical disaster. With the flies hanging in the air as thick as dust and a severe shortage of water, Barron said.

"The longer I stay here, I'm just so deeply moved by the incredible dignity and openness of these people. Under conditions of just intolerable deprivation they've just maintained their dignity and their discipline and are doing the best they can under these conditions," he said.

To listen to the entire documentary, click the audio player above.