Fed cuts key rate by a quarter-point

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

The Federal Reserve cut a key interest rate by a quarter-point Wednesday, a smaller move than the aggressive easing it undertook earlier this year. There were signs the Fed may believe it has done enough to prevent a deep recession.

The Fed action, after a two-day meeting, pushed the federal funds rate down to 2 percent, the lowest level since late 2004. It marked the seventh rate cut by the central bank since it began easing credit conditions last September to combat the growing threat of a recession brought on by a severe housing slump and credit crisis.

Commercial banks immediately announced that they were cutting their prime lending rate to 5 percent. That will mean cheaper credit for the millions of business and consumer loans tied to the prime.

The Fed move, which was in line with expectations, sent the Dow Jones industrial average momentarily soaring above 13,000 for the first time since January. But the Dow quickly gave up those gains as traders began to wonder whether the Fed was closing the door to further rate cuts.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Many private economists said they believed a Fed statement was signaling that the central bank may be through cutting rates unless the economy weakens much more than now expected.

"They are saying that unless we are surprised by further weakness, this is it," said David Jones, chief economist at DMJ Advisors.

Sung Won Sohn, an economics professor at California State University, said, "The Fed is telling us that this easing cycle is coming to an end fairly soon."

Analysts said the central bank seemed to be balanced between worries about economic weakness and concerns that inflation pressures are increasing. The Fed noted that it had done quite a bit already.

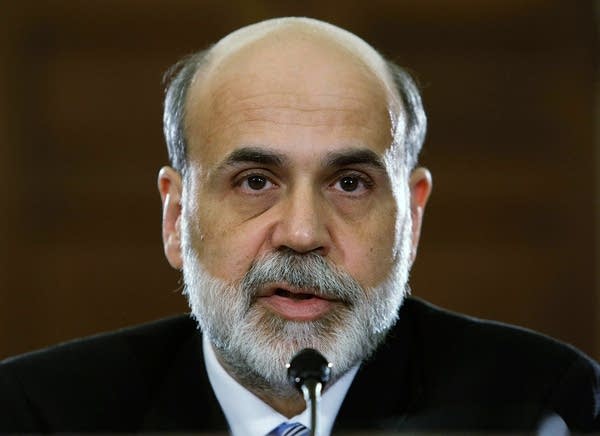

"The substantial easing of monetary policy to date, combined with ongoing measures to foster market liquidity, should help to promote moderate growth over time and to mitigate risks to economic activity," Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke and his colleagues said in their statement.

There were two dissents from the move. Richard Fisher, president of the Dallas regional Fed bank, and Charles Plosser, head of the Philadelphia Fed, argued for no change in rates. Both officials had also dissented at the March 18 meeting when the Fed cut rates by three-fourths point.

The central bank is walking a tightrope, trying to jump-start economic growth while also confronting the risk that if it overdoes the credit easing it could make inflation worse down the road.

Many economists believe the country has fallen into a recession. However, the government reported Wednesday that the overall economy, as measured by the gross domestic product, managed to eke out a 0.6 percent growth rate in the January-March quarter, barely in positive territory.

On the overall economy, the Fed's statement said, "Financial markets remain under considerable stress and tight credit conditions and deepening housing contractions are likely to weigh on economic growth over the next few quarters."

While officials said they expected inflation to moderate in coming months, they also said "uncertainty about the inflation outlook remains high."

The quarter-point move followed a string of more aggressive rate cuts ranging from a half-point to three-fourths-point in the first three months of this year as the central bank was battling to stabilize financial markets roiled by multibillion-dollar losses caused by rising mortgage defaults.

That turmoil claimed its biggest victim on March 16 when Bear Stearns came to the brink of bankruptcy and the Fed stepped forward with a $30 billion line of credit to facilitate a sale of the nation's fifth largest investment bank to JP Morgan Chase.

Credit markets, while not back to normal, have stabilized and many analysts believe the worst may be over - although they caution that this forecast could prove too optimistic if the housing slump deepens, causing even more mortgage defaults than now expected.

Before the Fed made its first rate cut in September, the funds rate had stood at 5.25 percent.