Minnesota entered statehood with an economic whimper

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Minnesota entered statehood in 1858 with an economic whimper. Just a few months earlier, the Panic of 1857 struck.

The good times leading up to the collapse were fueled in part by white settlers streaming westward.

Dozens, and then hundreds of white settlers a day arrived in St. Paul by river boat or on foot. They were lured by advertisements and word of mouth describing abundant and cheap farm land.

Speculators nabbed them as they arrived, and sold them land at increasingly inflated values. A young St. Paul writer, J. Fletcher Williams -- who would eventually become a founder of the Minnesota Historical Society -- witnessed the panic.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"The buying of real estate, often at the most insane prices and without regard to its real value, infected all classes and almost absorbed every other passion and pursuit," Williams wrote.

In his "History of the City of St. Paul," Williams observed the boom.

"Town-sites and additions to towns were laid out by the score. Many of these town-sites were purely imaginary, and had never been surveyed at all. Lots in these paper cities were sold by the hundred ... at exorbitant prices."

Nearly everyone was making money.

"The buying of real estate, often at the most insane prices and without regard to its real value, ... almost absorbed every other passion and pursuit."

The streets of St. Paul teemed with carpenters, bricklayers, blacksmiths and merchants prospering in the fast growing city.

A good number of them were swept up in the speculative fever and invested their hard earned cash in wildly inflated land.

The Panic of 1857 was set off by the collapse of a major New York City bank, and soon spread across the country. The territory soon to become the state of Minnesota was among the hardest hit, including a young St. Paul banker named Truman M. Smith.

The 32-year-old Smith had come west from New England to make his fortune, according to Joan Cotter, Smith's great-great-granddaughter.

The panic caused a run by depositors on her great-great-grandfather's bank, she says. Smith tried frantically to raise money and stay open.

"He started by mortgaging some property he had, and trying to cover the run on the money the people were coming to the bank to demand," said Cotter. "Eventually he had to close his doors, because he simply couldn't respond to the demand anymore."

Stores, banks and other businesses closed in droves.

Money, at the time issued by banks, literally disappeared. The cities of St. Paul and what would become Minneapolis literally had to print their own money -- or scrip -- so what was left of commerce could continue, says retired Minnesota Historical Society historian Rhoda Gilman.

"The whole monetary system collapsed because there was no federal standard monetary system, it was all bank notes and the banks were all prostrate," Gilman said.

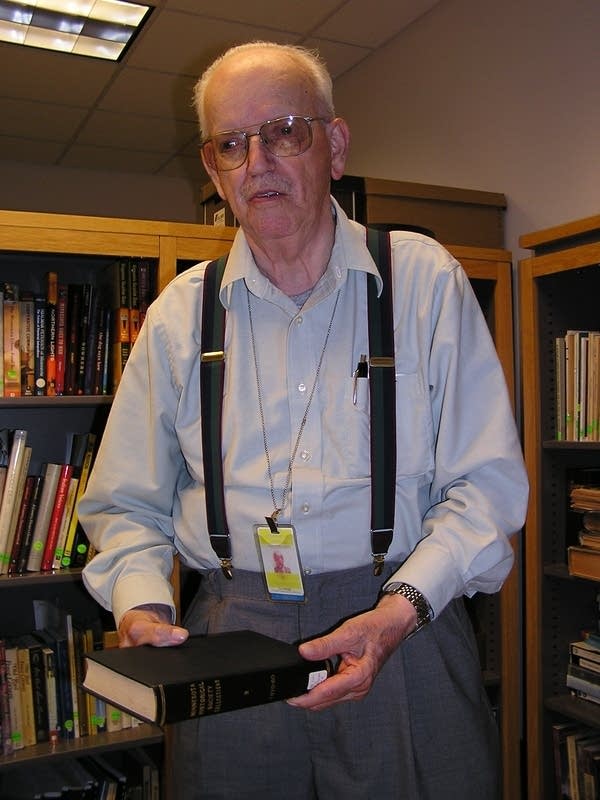

Lots of the newly destitute high-tailed it out of town to families back east, according to Alan Woolworth, a retired Minnesota Historical Society research fellow.

"Quite a few people left St. Paul. About half its population went somewhere else," Woolworth said.

The economic gloom hung like a cloud as Minnesota gained statehood in 1858.

Economic recovery arrived with this country's most ruinous conflict, the Civil War. Hundreds of thousands of Union troops needed food that was raised in abundance on Minnesota farms. Prices for farm goods shot up.

All sorts of other businesses had a big payday too including, Woolworth says, St. Paul photographers.

"[They were] taking pictures of young men going off to war, so they could buy them cheaply and send them back to their sweethearts and family," Woolworth said.

There were recurring speculative bubbles and collapses fueled by railroad building, mining and timber cutting.

The difference then was Minnesota and the rest of the country had lots of room for expansion and exploitation of resources, which often meant sudden rebounds that lifted people out of the economic soup.

A footnote to the story.

St. Paul banker Truman Smith lost his business and eventually his home in the Panic of 1857, but he reinvented himself.

He turned to commercial gardening, became the first leader of a major farm organization, the Minnesota Grange, and went on to become a leader of the Minnesota Horticultural Society.

The Ramsey County Historical Society will print an article about Smith this fall, in its quarterly magazine.