Fed plan could save millions from foreclosure

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

The foreclosure crisis has hit parts of Minnesota hard but, overall, Minnesota's rate of foreclosure is not among the highest. According to RealtyTrac, Minnesota had one foreclosure per 1,065 households in September. That ranked Minnesota 26th. Nevada had the worst rate, with one foreclosure per 82 households.

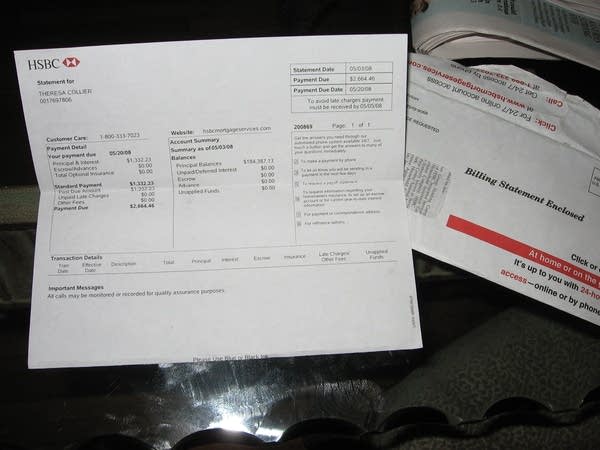

Every month, Theresa Collier sits at the dining room table looking at her bills, trying to figure out how to make it all work. But the math just doesn't add up.

Her job at North Memorial Hospital brings home $3,200 a month. Her mortgage payment is about thirteen hundred dollars and then she has property taxes, homeowners and car insurance and other household expenses. She has a tenant, but her renter pays just a few hundred dollars, not enough to make a difference.

"It's hard because even with my paycheck and my tenant, the money she gives me goes onto my mortgage to help me pay the mortgage," Collier said. "So that helps. Without her help, I'd be totally lost."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Collier's story is typical of the foreclosure crisis. She refinanced her North Minneapolis home in hopes of getting her monthly payment down by about $240. But, to her surprise, her payment instead went up, by about $500. The broker from Source Lending also told her she was getting a fixed rate mortgage when she wasn't.

"He just showed me some numbers and he said if I take option A then my mortgage would be $650 a month and the other one was my mortgage would be higher," she said. "Of course, I chose 'A' since the mortgage was going to be lower."

Desperation made her sign the papers, even though she found them confusing.

This summer, the Minnesota Attorney General sued her broker, Source Lending, for using "bait-and-switch" tactics like these. The suit alleges the company sold adjustable rate and interest-only loans to borrowers who were told they were getting a fixed rate.

After realizing what happened, Collier went to her lender for a loan modification but was told she didn't qualify. She owes more than her house is worth and is not behind on her mortgage.

"I'm trying to get help before I go into foreclosure. I don't want my credit to be bad," Collier says. "I worked too hard to build up my credit and get it to where it's at. If you mess up your mortgage it seems like you mess up everything."

Collier falls into the sort of limbo category of people who can't afford their mortgages, but get turned down for a modification because they are current with their monthly payments. There are no hard numbers on how many of these people there are, but according to the Mortgage Bankers Association, more than four million homeowners were at least one payment behind at the end of June, and half a million were in foreclosure.

John Courson, head of the of the Mortgage Bankers Association, said banks have beefed up their staffs to handle more requests for help and modifications are already up sharply this year over last year. But with the volume of struggling homeowners at an all-time high, lenders face a difficult choice when deciding whether to help people who are already in foreclosure or people who will be soon.

"If somebody looks and they are three months away, it's just the reality," Courson said. "With the resources they've got, they need to deal with the people that are there today and work on those folks as they also try to garner more resources to work back."

The association estimates that each foreclosure costs lenders a minimum of $30,000 to $50,000. Courson said that high cost is what's driving lenders to lower borrowers' principal and interest rates and avoid foreclosure.

But Brandon Nessen, from Minnesota ACORN, said the private sector acting alone doesn't go far enough. He said the government should establish a clear national standard for modifications.

"There needs to be much more ambitious and streamlined ways of offering loan modification options that don't require that individual discretion with each case," Nessen said. "What that allows is for the lenders to drag their feet and to be inconsistent with what they are willing to offer for people with different scenarios."

Right now, lenders consider each modification on a case-by-case basis. Establishing a standard debt-to-income threshold would streamline the process and automatically qualify millions of homeowners for help.

An announcement on the government's plan is expected soon and several major lenders have launched their own efforts to contact homeowners who might qualify for modifications.

Such plans would also help Collier because, even though she's not yet behind, she knows that when her rates adjust a few months from now, she will be. She is applying for another loan modification and said she's hopeful that, with the help of a counselor, she could finally get her interest rate down. But when Collier thinks about what the bad mortgage has done to her finances, she has a hard time containing her emotions.

"My kids never see me cry," she said. "I do it when I sleep, you know, but I just don't want to lose my home."

For now, Collier said she'll continue to hold on for as long as she can.