Ask a Neuroscientist: Sleeping and functioning skills

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

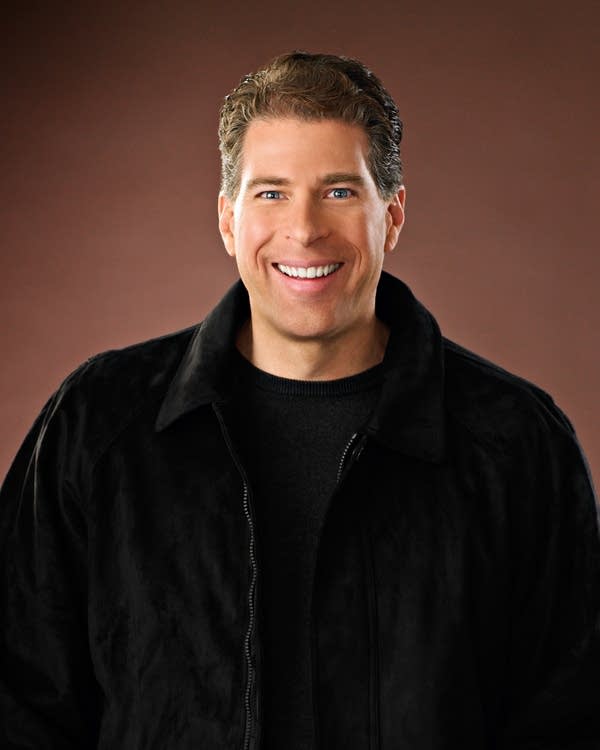

This is the seventh in an occasional series called 'Ask a Neuroscientist.' Today, we take audience-submitted questions to Paul Zak, the founding director of the Center for Neuroeconomic Studies at Claremont Graduate University and author of "The Moral Molecule," to learn more about how the brain works.

Judy submitted a question on our blog about sleeping: "I heard something recently about insomnia/reduced sleep influencing the brain in some way, possibly a dementia risk. What is known about this, and how does sleep with sleeping pills affect this risk?"

Paul Zak: Insomnia occurs in a variety of neurological and psychiatric disorders - and Judy is talking about a 2009 study in Science magazine, using rats, showing that rats that were prohibited from sleeping increased a protein in the brain that causes these plaques and tangles common in Alzheimer's disease and other dementia - and so there may be relationship between dementia and insomnia.

Another 2002 study in humans found that those who slept seven hours a night had the lowest risk for dementia - not six hours, not eight hours, but seven hours. And the theory seems to be these individuals are highly engaged in their lives - even as older adults. So there seems to be a tradeoff here between getting enough sleep - which improves the immune system, lets the brain reset - as opposed to being engaged in what you're doing and not wanting to sleep because you're going got hike a mountain in the morning or work on some new project.

So it seems to be a tradeoff - and it's not clear in dementia if insomnia is a cause or a symptom. So I think the punch line for listeners would be "enough sleep is essential for a healthy brain and immune system... and occasional use of sleeping pills is okay." Sleeping pills put you into a deeper sleep faster than the normal sleep patterns. That doesn't seem to be a big problem with individuals who suffer from dementia. Enough sleep's important, but also being really engaged in activities around you. You know, this is common for people into their 90s who will be really engaged.

Tom Weber: It's weird the number seven hours of sleep might have more positive effects than eight, and yet, your reason behind it has nothing to do with the number of seven - it's the activities outside of sleep.

PZ: That's exactly right, so it's really being active but still getting enough sleep. I should also say as people age, they sleep less at night and tend to make up the time with naps during the day. And so if your total sleep time in a 24-hour period is in that seven hours a day range, you're probably okay.

We also asked Paul this question from Jenny, who submitted a question on our blog about cognitive impairment. She's a speech pathologist and wonders if there's any research that looks into ways to improve poor executive functioning skills.

PZ: So there are several kinds of software you can purchase that claim to train the brain to focus better to potentially increase IQ. The research so far shows only short-term effects on cognitive performance from this software. Having said that, the idea that you can improve brain activity, particularly executive function of the brain, is not without really solid research that it works. So the key to getting good at anything is repetition. In the brain it's called "long-term potentiation." It means you do something over and over and over, and you strengthen the connections of the brain between neurons.

So doing something over and over is important, but here's some interesting new research: You can stimulate the growth of new brain cells through exercise. So brain training using software is okay, but the proven way in humans and animals is mild aerobic exercise. You might even combine those. So if you want to learn French and listen to tapes, if you did that while you're walking for an hour a day, you'll get a double whammy and get the benefit of both of those functions.

TW: But when you're talking impairment, it seems if repetition helps you learn it, if there's an impairment that requires a speech pathologist to get involved, that also suggests that part of the brain is damaged.

PZ: So my advice is quite general and it doesn't apply to specific individuals who have dysfunction, for example, in speaking. So people who have had a stroke, much of their therapy starts with simple repetitive behaviors - start by saying your vowels. Just work on 't-h's' A lot of this is repetition, but how it's done requires a trained speech pathologist to guide that. But again, repetition would be the key

Submit your 'Ask a Neuroscientist' question.

Follow Tom Weber on Twitter at twitter.com/webertom1

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.