Artist links native quillwork and abstract painting

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

At first blush, you might not think Native American beadwork and quillwork would have much in common with contemporary abstract painting.

But Dyani White Hawk's new show at Bockley Gallery in Minneapolis proves otherwise.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

White Hawk, known as the curator of All My Relations Gallery, has put together a bold body of work for her solo exhibition that primarily pulls from the past two years.

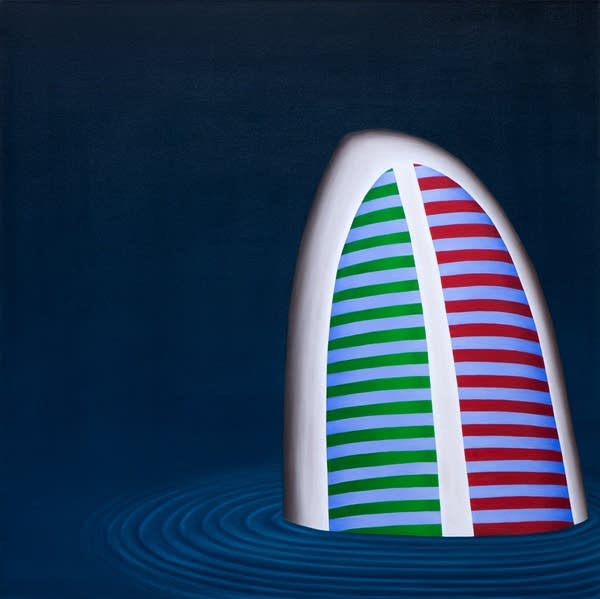

The exception to that rule is her 2011 painting "Self Reflection."

"It marks the beginning of the use of that shape, which references moccasin tops," explained White Hawk, a member of the Sicangu Lakota tribe. "I’ve referenced it a lot since then."

While in grad school, White Hawk worked to marry what she'd learned from native arts and her mainstream Western arts education.

"How do I embrace all those things in my work? How could I communicate both very directly with native people, and with those who are more familiar with western art systems – especially modern abstraction and abstract painting?"

The moccasin shape was birthed from that quest. It took on its own life as a figure that was sexless, ageless, and flexible. It could operate as an abstract image while still connecting with Native American symbology.

"It’s what grounds us," White Hawk said. "In addition to being the literal connection between your body and the earth, moccasins are at the core of your tribal identity. How it’s made, what it’s made out of, the ornamentation and color scheme all speak to where you come from.

As an undergrad, White Hawk would simultaneously paint and do more traditional beadwork and quillwork. But once she started graduate work, she felt pressure to focus on her painting. So she decided to incorporate the imagery and design from the quill and bead work into her paintings.

"I needed to do both to be fulfilled," White Hawk said. "So I started mimicking it in paint, and somehow that fulfilled the need to be doing it. I was using the aesthetics, pulling from those motifs. There was enough of a connection that it made sense."

For White Hawk, the path from her Lakota traditions to contemporary abstraction is a natural one.

“Moccasins, leggings... they do the same thing as abstract paintings," explained White Hawk. "They convey content and stories, they extend generations worth of conversations and symbolism through abstract practices. It’s just a different context. There’s so much content but people aren’t taught it, so they just think they’re pretty designs.”

In art school, White Hawk found herself drawn to the work of Marsden Hartley, Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb, only to learn they had been inspired by native art.

"But it’s just lightly referenced," she said. "The Native American peers they were drawing from don’t get the credit – it’s the western painters that influenced them that get the credit. Native American art is seen as 'craft' – so it’s not held in the same esteem."

For White Hawk, the categorization of Native American art as craft is frustrating -- and misleading.

"The amount of inspiration that western artists have gained from Native American art has not been given due credit," she said. "These things are so intertwined; you can’t unravel the relationships. Native American art wouldn’t look the way it does today if it weren’t for interactions with western people. And Western art wouldn’t look the way it does today if it weren’t for interactions with Native Americans. So trying to separate them out as different is just not real."

Her most recently completed painting, "Resilient Beauty," speaks to that intertwined relationship.

The right hand side depicts cotton calico, a fabric that was once a common trade item and so integrated into native fashion that it's now considered "traditional." The left hand side depicts quill work being laid down with a lazy stitch. But the lines refuse to lie down, and even the calico flowers appear to be peeling off the canvas.

"It’s my attempt to signify the multitude of influences on my work, through contrast and contradiction, while still maintaining a sense of balance and tension," White Hawk said. "The painting refuses to be stagnant – it won’t lie still. It speaks to the beauty of native art forms and how they change as they respond to contemporary times. Native art forms are both 'beautiful' and 'resilient.'"

"Into the Light: Paintings and Prints by Dyani White Hawk" runs through Aug. 2 at Bockley Gallery in Minneapolis.