Minnesota ramps up hunt for arsenic in wells

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

On an unexpectedly warm March afternoon, Emily Berquist knelt in the slick mud of a recently cleared driveway, a plastic sample jug wedged between her thighs. In her hands, she held a filtering tube attached to a pump powered in turn by the battery of her nearby Chevy Equinox.

The car idled with its hood up, urging a thin stream of water into the tube to remove sediment from the well water just collected outside a new house on a patch of wooded land near St. Michael, at the northwestern edge of the Twin Cities exurbs.

"It's only mud," said Berquist, a hydrologist with the Minnesota Department of Health, significantly downplaying the quicksand-like snowmelt. Soaked to her knees and careful to handle only the outsides of the containers amassed before her, she said, "I did this when it was 18 degrees. That was hard. My fingers were freezing."

Berquist was completing the second of three tests for arsenic in the drinking water well. The tests are part of a new three-year project between the health department and the U.S. Geological Survey designed to improve the way arsenic, a carcinogen, is measured in private wells and to develop guidelines to help contractors avoid drilling high arsenic wells in the first place.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"I was naive to arsenic."

This is important in Minnesota because the state's geology has left groundwater in some areas with elevated levels of naturally occurring arsenic.

The home where Berquist was testing the water belongs to Melissa Miller, a substitute teacher, and her husband Joshua, a heavy equipment operator. Miller, who is pregnant with the couple's third child, had many concerns when building their house last year. But the prospect of arsenic in the water, which is odorless and tasteless, never crossed her mind. "Honestly, it was not on my radar," she said. "We had the land surveyed before we bought it to make sure we could get septic and a well. We did some soil samples. But I was naive to arsenic."

Since 2008, all new wells in Minnesota must be tested for arsenic. This requirement has increased awareness of a problem that is pervasive, especially across a swath of the state stretching from the northwest corner to the south-central border with Iowa. Glaciers advanced and retreated along this path, known as the Des Moines lobe, tens of thousands of years ago, depositing arsenic-rich sediment. The arsenic, a common element, likely originated from shale scooped up in Canada and the Dakotas.

The arsenic problem isn't new to Minnesota, but people like Berquist are redoubling their efforts to understand it and mitigate its effects.

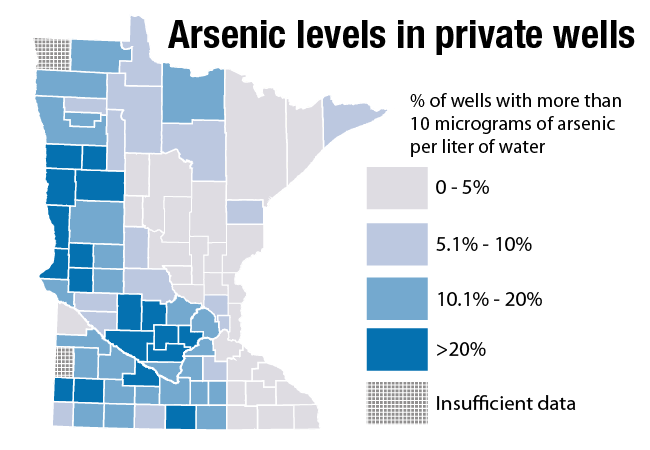

The state estimates that 10 percent of the approximately 450,000 private wells in Minnesota have arsenic levels that exceed the current federal standard. In some counties, like Clay and Norman, near Fargo, the percentage is much higher, 39 and 44 percent respectively. For all counties see this Minnesota Department of Health interactive map.

In Wright County, where the Millers live, nearly 20 percent of private wells are contaminated. Initial sampling late last year showed their well was at an acceptable level, about half the limit set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. The maximum allowable level is 10 micrograms per liter. (A microgram is one millionth of a gram.)

Even so, when Berquist contacted Miller about participating in the re-testing study, Miller thought it sounded like a good idea. "It's a free study, I am going for it," she said, standing on the mud-strewn front porch of her house, her youngest daughter, Riley, on her hip. "We have two kids and one on the way. The third is due next month. That is all the more reason to do this."

Arsenic exposure over time can increase risks of liver, bladder, lung and other cancers, along with nervous system problems, diabetes, and high blood pressure. Some studies also link it to reduced IQs in children. In 2001, the EPA lowered the acceptable arsenic standard from 50 micrograms per liter to 10, with compliance required by 2006. Municipal water supplies in Minnesota complied by treating and filtering. But private wells are less regulated, and it's largely up to landowners whether and how to treat.

"We are certainly in the mix of places in the U.S. that have widespread arsenic issues."

One of the aims of the testing project, which received a $650,000 grant from the state's Clean Water Fund, is to determine the accuracy of initial samples taken "off the rig" when a well is drilled. "They take a sample at the beginning," said Mike Convery, a former supervisor with the Department of Health's Well Management Section. He co-wrote the study proposal and retired from the department in early March. "It's hard to say that is a natural situation there. They have just drilled a well. They have disturbed lots of stuff. It's not back to its normal condition. We want to find out if that is representative over time. We want to get a better handle on what the real concentrations might be."

As part of the study, Berquist will test as many as 250 new wells—mainly in the Des Moines lobe area plus some in northeastern Minnesota—and retest them after three to six months and again after a year. The goal is to see if arsenic levels go up or down or stay the same over time. So far, she has tested around 130 wells and retested just a sliver of those. Berquist said it's too early to draw conclusions, but at the end of the study, in 2016 or possibly 2017, the departments will release their findings.

Arsenic contamination in Minnesota is widespread, but manageable compared to other places in the world, like India and Bangladesh. The state is similar to much of the upper Midwest and New England, where glaciers also left their marks. "We are certainly in the mix of places in the U.S. that have widespread arsenic issues," said Mindy Erickson, a hydrologist and groundwater specialist with the U.S. Geological Survey. While most of the state's well concentrations are below 10 micrograms per liter, she said, "We have a significant percentage between 10 and 100."

The study, she said, will enhance understanding of the wealth of information already gathered and kept by the state, such as a database of 23,000 wells that have been tested for arsenic. After an update this month, the total will be 30,000. Minnesota does some of the most extensive sampling in the country. "It's just all coming together right now," Erickson said. "We have chemistry and geology and small-scale studies we can bring to bear in a few places."

Drilling clean wells in the Des Moines lobe can be difficult. Drillers look for sand and gravel layers in which to place a well screen, or water intake, but these layers can be very thin. To make matters more complicated, the sand tends to be sandwiched by clay. "When the glaciers laid things down, they mixed and matched things," said Ron Danielson, co-owner of the Mork Well Company in Nowthen, north of the Twin Cities. "We can drill two wells at properties right next to each other and have the same depth on both wells and the arsenic levels might come out different. One might be two and one 12."

"It's either something we are doing that is messing up the test results, or there is something with the geology where this stuff can vary," said Danielson, who is assisting with the state study. "As a well contractor, our goal is to see if there something we can do on our end. Can we drill deeper or shallower? Is it better to take water from the top of the aquifer or the bottom? It's pretty much trial and error out there." Or perhaps the drilling process itself artificially affects the arsenic test results. "We are not scientists, we are well guys."

"If there is a better way to do this," Danielson said, "I'm all for that. It's something we really need to know."

"If there is a better way to do this, I'm all for that."

The study could lead to new state codes designed to help well contractors reduce the likelihood of drilling high-arsenic wells. "We are not quite at that point yet," said Convery, noting that many contractors have been eager to cooperate with the project. "We want to give them some guidance on reducing their chances. They end up with an unhappy customer who blames them for arsenic. Then they have a hard time getting paid."

Based on examinations she did previously, Erickson thinks she already has a useful guideline. She discovered that if well drillers can put at least 10 feet between the overlying clay and the well screen in the sand, arsenic levels in drinking water tend to be lower. "That is one of the things we will test with the larger data set," she said. "We will have to see if that hypothesis holds."

Arsenic, Erickson said, "is not straightforward and simple. It's tricky and elusive and complicated and it's really important to help people avoid it."

One of the most dramatic cases of arsenic poisoning in state history happened in 1972, near Perham in central Minnesota. A construction company drilled a drinking well directly into a long-forgotten arsenic disposal pit. Back in the 1930s and 1940s, farmers had used sawdust mixed with arsenic and molasses to kill grasshoppers. Employees of the construction company drank water from the well, which contained an astounding 11,800 micrograms of arsenic per liter. First, workers developed gastrointestinal symptoms. Then, a few developed neurological problems and numbness that landed them in the hospital. At least two suffered long-term nerve damage and loss of feeling in their hands and feet.

In more common lower-dose exposures, it can be hard to separate arsenic's impacts from other factors: If a farmer develops skin cancer, it's difficult to know if that's because of arsenic or prolonged exposure to the sun.

"The health effects we know about with arsenic come from studies where the concentrations are much higher," said Jean Johnson, the Department of Health's Environmental Epidemiology Supervisor, who has worked on arsenic studies in the past, including early mapping of Minnesota wells. "We know that cancer is one of the effects, but it manifests over time. And it is also a disease that has other risk factors. Trying to parse out what portion of cancer is attributable to wells is very difficult and probably would not be successful."

The testing project could help lay the groundwork for further analysis of the health effects in Minnesota, she said. "If we have a better understanding of exposure, we have a better chance of measuring health outcomes."

For landowners with high-arsenic wells, the solution is to filter drinking water. Options include reverse osmosis, which can be expensive, and simpler in-line cartridge filters that tend to cost less. "There are a variety of treatment systems," Convery said. "It's still a little of an art to figure out which works best for particular well water." In any case, "Go with someone experienced in the area. Don't just reply to a 1-800 number that appears at 2:00 in the morning on TV."

On the porch in St. Michael, after the water samples had been painstakingly collected and filtered, Berquist and Convery discussed with Melissa Miller what to expect. Test results would come back in a month or more, and Berquist would return for a third arsenic sample in six months.

"Do the results change?" Miller asked.

"That's what we're trying to figure out," said Convery, noting that Miller's manganese levels were high and she should consider bottled water for baby formula.

"That's good to know," she said, as her older daughter, Reese, appeared in the doorway with a purloined peanut-butter bar. "Until you contacted me, I didn't know this was an issue. It's good you reached out to me."