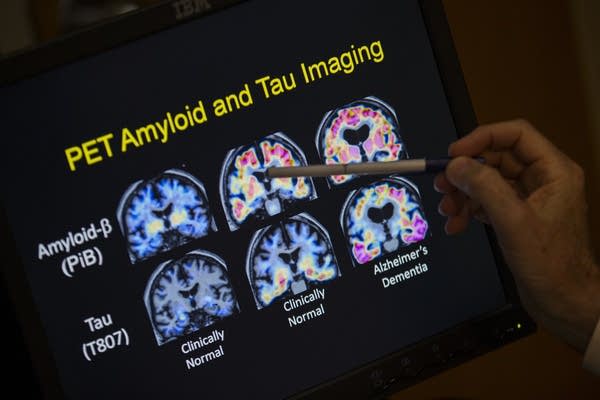

New way of defining Alzheimer's aims to find disease sooner

Government and other scientists are proposing a new way to define Alzheimer's disease.

Evan Vucci | AP 2015

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.