As fentanyl seeps into drugs, activists urge users to test

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Chuck has been struggling this spring with anxiety and nausea. He describes the sickness as "a nightmare." For days, he stayed home, building back his strength and swallowing tinctures of herbs like skullcap and passionflower as his body withdrew from opioids.

He ventured back outside on a sunny Friday afternoon. A 33-year-old Midwesterner with a slight beard, Chuck smokes cigarettes to calm his nerves on his friend's back patio.

A user of heroin and other drugs since his early 20s, Chuck said he's always been able to get sober when he wanted. But opioids have been harder to kick lately, as the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl has seeped into drug supplies.

"People get sick a lot faster than they would from what used to be out there, from standard heroin or pills and that sort of thing," Chuck said. "It's a lot harder for people to stop doing it."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Fentanyl is cheaper and stronger than heroin, so it can be used to bump up the strength of heroin and other drugs. But because there's no telling the strength of the fentanyl in a doctored drug, it's also more likely that people could overdose after taking drugs that contain fentanyl.

Chuck, who asked not to be identified by his full name due to stigma against injection drug users, first heard about fentanyl about three years ago. He was planning to visit friends in Chicago when he got a message on Facebook about a memorial concert. It was being held in his friends' honor. The couple had overdosed on fentanyl and died.

"It was during the first big waves of overdose from it," Chuck said. "And it definitely opened my eyes to that pretty quickly, hitting that close to home."

That fentanyl wave is breaking in Minnesota, and other nearby states, according to public health experts. The number of overdose deaths attributed to fentanyl last year in Minnesota jumped more than 70 percent from the year before.

Some grassroots activists, and people who use drugs, are trying to reduce the risks by handing out a little piece of paper called a fentanyl test strip. It's a simple way for people to tell whether there's potentially dangerous fentanyl in the drugs they're about to put into their bodies.

Chuck has tested three different batches of heroin in the last few months. Each batch tested positive for containing fentanyl. He and others still shot up the drugs. But knowing it was in there changed how they approached it.

"People just do things a lot more slowly, or test out the first bit of it quite a bit more slowly, because people are aware of how strong it is," Chuck said. "Definitely a lot more cautious."

Overdoses kill 30,000 Americans annually

Activists handing the fentanyl test strips out in the Twin Cities say it's one more way to reach people who are not only threatened by overdose, but by the prospect of criminal charges or social shunning if their drug use becomes known.

Chuck is one of the about 1 million Americans who uses heroin each year. Many more illegally use prescription or synthetic opioids. The opioid overdose epidemic, as it's known, now kills at least 30,000 Americans each year.

In Minneapolis, Brit Culp is one of the activists who has started to distribute the fentanyl strips to people most at risk for overdose. Sometimes they may follow what Culp calls "breadcrumbs," a baggie, a little orange syringe cap or other clues that people are regularly using heroin nearby. They carry clean cookers, cottons and needles, as well as the opioid overdose medication naloxone. They take used supplies and safely dispose of them. They never take names.

"There's a lot of consequences related to the war on drugs and prohibition, so it has to be discreet and under the table," Culp said. She tells people, "'I know you're going to use today, and that's cool, but I want you to be safe in the process.'"

Activists like Culp are all volunteers, and they mostly cover the costs of the $1 strips out of their own pockets. In the first two days they had the strips, activists say they gave out all 300 strips.

'OMG, I'm scared'

Culp and others had noticed more fentanyl in the state's black market drug supply, including in non-opioids like cocaine and meth. But people had no way to know if they were getting pure heroin or something else laced with powerful fentanyl.

That's where the test strips come in.

The test can be conducted with a very tiny amount of drugs. Even the residue left in a baggie or in a cooker is enough.

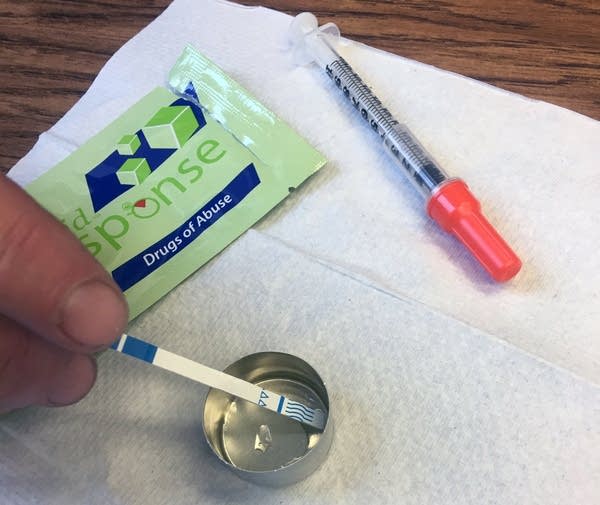

It comes in a little green packet that contains a single strip of paper. One end is dipped into a tiny bit of water mixed with drug residue. They hold the strip in the mixture for about 15 seconds and results should appear within a couple minutes.

One line appearing on the strip means the drugs are likely positive for fentanyl or one of its drug analogues. Two stripes mean it probably didn't have fentanyl, although it could.

"People will say, 'No, I know this guy who is my dealer, I know he doesn't have it,'" Culp said. "I'll say, 'Here's this strip, why don't you just test it, and just be sure.' And they'll send me back a picture with only one line saying, 'OMG, I'm scared.'"

Not FDA approved

The test strips are not approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this particular use and state agencies in Minnesota are not distributing the test strips to their programs.

But the Minnesota Department of Health's Kathy Chinn said she's hearing anecdotally that volunteers in the state are doing a good job telling users how to safely use the strips and respond to fentanyl in drugs.

"The harm reduction model is really what we want to emphasize here," Chinn said. "Fentanyl test strips can be a great tool in having those conversations and reducing harm."

Chinn said there is a danger that users can get a "false sense of safety" if they don't understand or aren't told about the limitations of the test strips.

Strips not perfect

Grassroots activists and drug users in Minnesota aren't the first to adopt the fentanyl strips. They've been used in Europe for a while. And areas hard-hit by the opioid overdose epidemic on the East Coast have helped pioneer the strips in the United States.

Jess Tilley, executive director of the New England Users Union, said her group exists to "speak for the drug users who can't speak."

Tilley warns people to treat all drugs like they contain fentanyl, even if they don't test positive: "Don't use alone, do a tester shot, go slow, carry naloxone."

The fentanyl test strips aren't perfect in detecting all forms of fentanyl, she said. And they have no way to show how pure that fentanyl might be. But the strips are a way to start talking about fentanyl.

"An educated drug user is an empowered drug user," Tilley said. "Education is empowerment, and even though it might be kind of controversial because we're talking about supplies and tools that enable somebody to use drugs, it's still enabling them to stay alive."

It's not just education though, Tilley said. It's also about changing the culture where drug users, especially injectors, use drugs alone and risk overdosing without help.

"Drug users do care about one another and care about their community and want to keep people safe," Tilley said. "Even the way word spread about fentanyl test strips, it took talking to a few drug users in my town and it spread like wildfire."

Enabling safety or enabling drug use?

The fentanyl test strips do present a gray area in the law. They could qualify as drug paraphernalia under Minnesota and other state laws, but grassroots activists across the country say that they haven't heard about any prosecutions. Tilley said she's worked with law enforcement in her area to be sure police know the sort of work she's doing isn't enabling drug use but is enabling safety.

"I'm very, very clear that the testing I did is only done on residue or used equipment, things I'm gathering off the street anyway," Tilley said. "A lot of the police right now, or police departments, they don't want to prosecute people, they want there to be solutions and life-saving tools."

In Minneapolis, city spokesperson Casper Hill said the city attorney's office hasn't had to consider the issue yet, but that the "city supports efforts to preserve life and safety."

The Minnesota Department of Health did not have any comment about the paraphernalia law.

Other states and some cities are moving forward in making the strips more widely available.

This month, language that explicitly exempted the fentanyl test strips from paraphernalia laws went into effect in the state of Maryland. That change came in the wake of a study published by professor Susan Sherman at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The strips are innocuous enough that it would be hard to imagine someone being arrested for them, Sherman said.

"I think the decriminalization engenders the sense of safety, but people have been doing it anyway," Sherman said. "It's really as much for the organizations handing them out than anyone else."

'People want to be safe'

Sherman's study looked at "drug checking," using a variety of methods. But the strips were the most effective method at determining when fentanyl was present and could detect it at the lowest levels.

"People who use drugs are like anyone else, of course, people want to be safe," Sherman said of drug checking. "It gives autonomy back to people that don't always know what they're putting in their bodies."

Almost 90 percent of the drug users surveyed in the study said they thought the strips would help reduce the chances of overdose, and 75 percent said they'd change their behavior if they found out drugs they were using contained fentanyl.

"People are often, in this opioid epidemic, interested in talking about prevention, and talking about treatment, but most people are actively using drugs and not ready to quit," Sherman said. "The road to recovery is paved with a lot of relationships and this is one more way to build relationships."

That's a sentiment Chuck agrees with. The education and clean supplies are important, but the support of one's community is what many people who use opioids really need.

"In the age of fentanyl, [it's] people being able to alert each other that there might be a danger," Chuck said. "Just because people are doing drugs doesn't mean they want to die — most people want to live and get through these struggles."