Hennepin County begins project to assess sinkhole risk

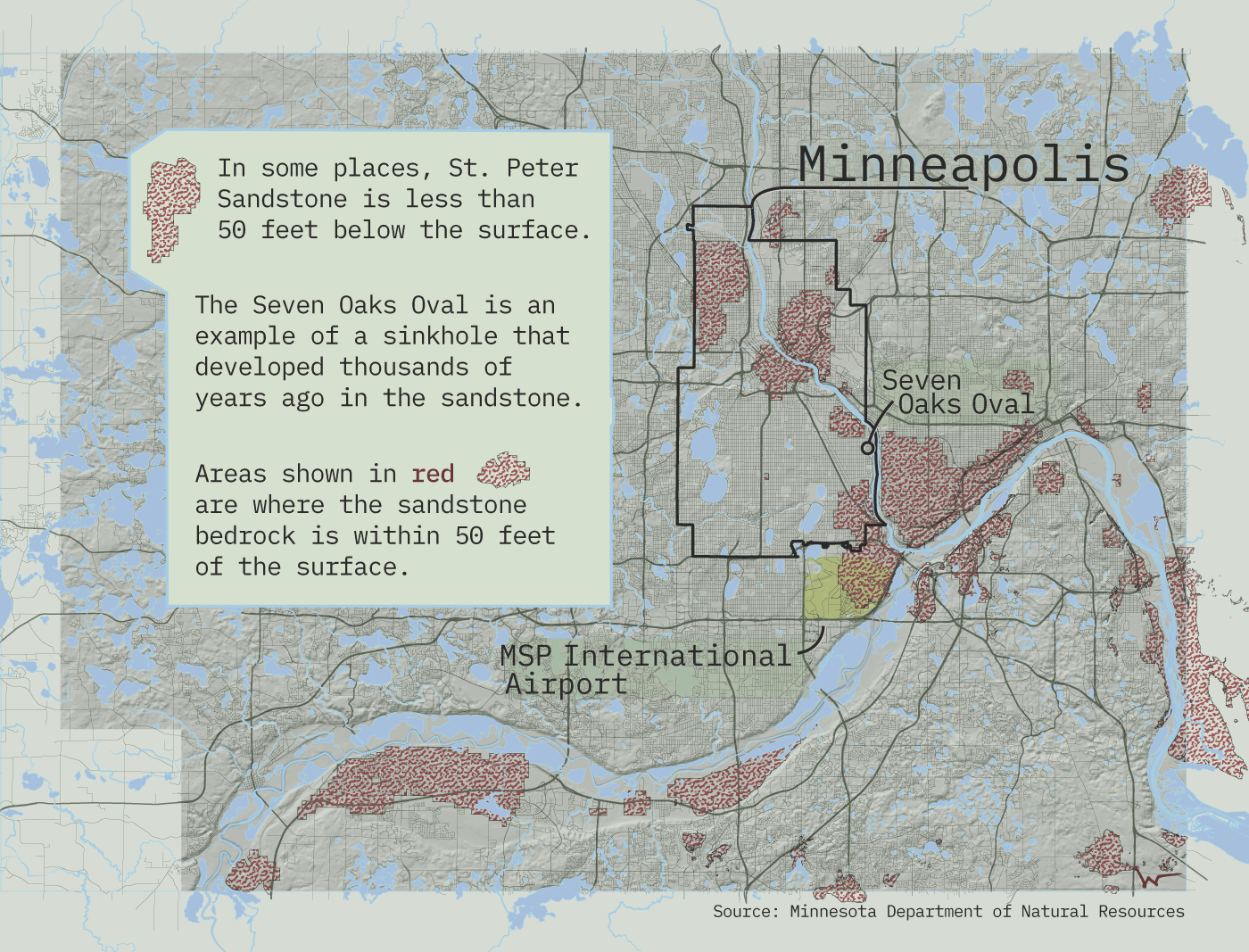

Across the Twin Cities there are areas where the bedrock is just beneath the surface. In Minneapolis this covers most of downtown and the area around MSP International Airport.

William Lager | MPR News

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.