The science of coronavirus: Your questions, answered

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Researchers are hot on the trail of the new coronavirus. They’re looking for its weaknesses in hopes of stopping it from spreading and putting those who get COVID-19 in a better position to fight it.

Kerri Miller and listeners talked with virologist Angela Rasmussen and infectious disease fellow Dr. Megan Culler Freeman this week about what we know about the virus; how it enters and affects our bodies; and what we have yet to learn.

Below are some of the interview’s highlights, which have been edited for clarity and brevity.

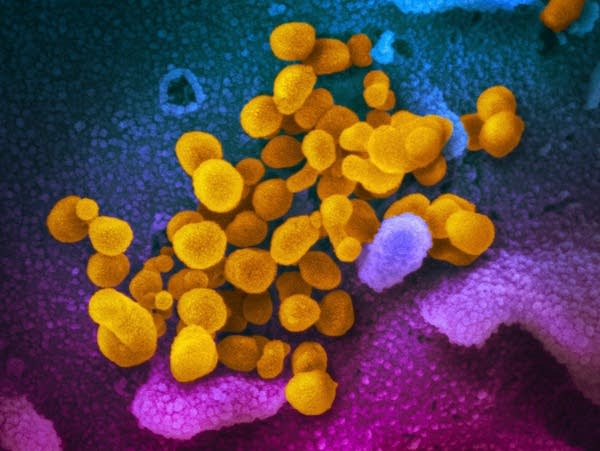

Does the novel coronavirus look like other viruses? What does it mean when people say it’s surrounded by oily molecules?

Angela Rasmussen: The oily molecule that you're referring to is actually the viral envelope, and that is derived from the membrane of the host cell that it's affecting. So as much as that oily envelope is encircling the virus, it also is what encircles every single cell in your body. That can be disrupted with soap.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

When the virus particle is out in the environment, for example, such as on your hands, the soap itself disrupts the oily layer that's in the middle of that envelope. When it's disrupted, the spikes (the pointed things we see in close-up pictures of the virus), which are needed in order for the virus to infect a host cell, are removed from the virus.That renders it inactive.

What if the virus gets inside our bodies? What does it do then?

Megan Culler Freeman: A lot of the disease that we experience is the virus replicating. There are cells in your body that have the receptor ACE-2 — it acts kind of like a lock-and-key mechanism. So, the spikes are the key on the outside of the virus and it has to find a cell with the appropriate lock to unlock and to be able to replicate in that cell.

Any cell in your body that expresses that receptor ACE2 — and we find it in many parts of the body (blood vessel cells, lungs, intestines) — would be able to support replication of the virus. And then part of the disease that you experience is the virus replicating in the cell, but also your immune system responding to that threat. A lot of the illness that we feel, especially like body aches, is actually your immune system responding to that virus.

When we feel the symptoms of COVID-19, is this your immune system responding?

Culler Freeman: Your immune system is what makes you have a fever. Your immune system is what brings some of these other, we call them inflammatory molecules, to the places where the virus is replicating to try to get rid of it. But it's a delicate balance. A lot of times, inflammation means fluid and if you're bringing a lot of fluid and inflammation into a place like the lungs that don't tolerate fluid very well, you can have pretty severe lung disease.

What happens when infection of this virus turns fatal?

Rasmussen: That is something that's still very much under investigation in terms of the specific steps that lead to death or disease. I study the host response to infection overall. What we found for other viruses that are similar, including viruses such as MERS coronavirus, is that it's not so much an overreaction of the immune system as it is a loss of regulation that results in an overreaction, specifically of the inflammatory components of the immune response.

It's not so much [that] you have a weaker immune system; it's that you lose the ability to control these very specific responses that normally occur to contain the virus. The way this is supposed to work is that if you are infected, chemokines and cytokines are secreted by infected cells or cells nearby that recognize that there is an infection. They recruit immune cells to come, contain the virus, keep it where it is and clear it from the body.

Hopefully, you would have acute symptoms that would then resolve. The severe disease is likely to result from where that process goes wrong. It becomes unregulated and there is an inflammatory state that can itself be pathogenic or harmful to the patient.

What do we know about the incubation period?

Culler Freeman: One of the unique things about this virus is that the incubation period, which means if I as a person come into contact with the virus on day zero, I might not develop any symptoms at all until day 14. Now, on average, people will develop symptoms somewhere in the neighborhood of five to seven days.

But during that time, the virus is replicating and you are able to shed virus from your nose. That means if you're out and about at the grocery store touching your face and touching shelves, then you would be able to be a proponent of viral spread in the community without really even knowing that you were sick. And that is what is making this virus so difficult to control and why such an emphasis has been placed on social distancing measures.

What do we know about how contagious it is? What is the reproduction factor?

Culler Freeman: The reproduction factor is often what we think about how contagious a virus is. So if we think about the replication number of a virus, the most contagious virus that we know about is measles, an airborne virus, and one person with measles can infect somewhere in the neighborhood of 12 to 18 other people who are at risk for that virus (people who haven’t been vaccinated and don’t have immunity.)

We're still learning about what the infectious value of this virus is, but estimates are in the neighborhood of two to three, which means for each person infected, they can go on and infect two to three people and then those people can infect two to three people. That's why we're seeing this exponential growth in the number of cases that we have around the world.

Is this virus mutating?

Culler Freeman: Coronaviruses are a little bit unique. They have an RNA genome, which is the genetic material that we're able to detect with our tests. A lot of times, we think about RNA being less stable than DNA (DNA is what people's genomes are made of). One of the hallmarks of DNA genomes is that they are able to check for errors. Most RNA genomes can't do that, so that means as they're going on and replicating, they might make a mistake.

But they wouldn't notice that they make a mistake. This is how mutations occur and this is how viruses are able to change. Coronaviruses actually do have some RNA proofreading capabilities, which means while they can still mutate, they do not mutate nearly as rapidly as some other viruses, like the flu.

So, we have been able to use genetic sequencing of viruses that have been isolated to demonstrate that there might be some subtle differences, but there haven't been huge genetic differences that have yet been identified.

Is it true that people who have the virus notice problems with their senses of smell and taste?

Culler Freeman: I will say that I have not seen any published data that this is true. We are still learning about this disease. So, I wouldn't completely count it out, but if you're following along out there at home, I wouldn't necessarily consider that one of the early symptoms.

Does it matter that we know how many cases of COVID-19 there are? Or just how many severe cases there are?

Rasmussen: It matters to us to know both because so many cases are very severe and need hospitalization, as most people know. Right now, our hospital systems are experiencing a great deal of strain and that's only going to get worse as more severe cases occur.

But that's exactly why we often need to know how many mild cases there are, because people who are asymptomatic, presymptomatic — meaning they haven't yet developed symptoms and have very mild disease — are all capable of transmitting this virus to others. And those others may go on to develop severe illness.

To listen to the full conversation you can use the audio player above.

Subscribe to the MPR News with Kerri Miller podcast on: Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify or RSS.