Dispute over environmental fund leaves projects on wolves, weeds and mussels in limbo

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

For the past several years, University of Minnesota researchers have studied wolves in Voyageurs National Park to learn how they spend their summers.

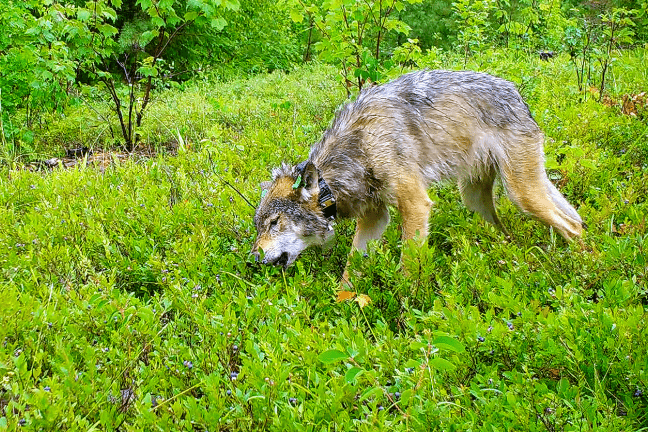

They’ve uncovered some fascinating details. Wolves are often thought of as bloodthirsty carnivores that hunt large mammals. But in the summers, the researchers tracked them catching freshwater fish — and even feasting on wild blueberries.

The research requires funding for staff salaries and equipment. The collars fitted with a GPS device that researchers use to track the wolves cost more than $2,000 each, said Joseph Bump, associate professor in the university’s Department of Fisheries, Wildlife and Conservation Biology.

To cover those costs, the Voyageurs Wolf Project received $293,000 from the state’s Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund in 2018. This year, researchers had hoped for another $575,000 from the fund to launch the project’s second phase.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

But that plan is now uncertain. The project is one of dozens benefiting Minnesota’s natural resources that are now in limbo because of a political dispute at the state Legislature. At the center of the stalemate is a years-old disagreement among state lawmakers over whether the trust fund should be used to pay for wastewater treatment projects.

The uncertainty has left many researchers and conservation officials wondering about the future of their work. If the funding doesn’t come through this year, the Voyageurs Wolf Project “will not continue or likely recover,” Bump said.

“We’ll be in a scramble mode,” he said. “We’ll hope to finish out the field season, which ends at the end of October, and then we’ll just see what happens next.”

The Environment and Natural Resources Trust Fund was established in 1988 by a constitutional amendment approved by a majority of Minnesota voters. The fund receives proceeds from the state lottery every year for the "protection, conservation, preservation and enhancement of the state's air, water, land, fish, wildlife and other natural resources."

The projects waiting for funding have already gone through a complicated and competitive selection process, said Steve Morse, executive director of the nonprofit Minnesota Environmental Partnership. He said it would be “grossly unfair” if they can’t go forward when the money is available.

“There will be people [who] will be laid off and projects that will be lost in mid-course, if they decide not to proceed,” Morse said.

Clash over wastewater

Typically, the 17-member Legislative-Citizen Commission on Minnesota Resources recommends which proposed projects should get funding. In most years, the Legislature approves the recommendations without significant changes.

But this year, the commission didn’t make its usual formal recommendation this year because of that disagreement over wastewater treatment plant improvements.

Last month, Sen. Bill Ingebrigtsen, R-Alexandria, a member of the commission, sent a letter to the House environment and natural resources committee chair, saying the Senate isn’t interested in passing a trust fund spending bill this year.

Ingebrigtsen’s letter to Rep. Rick Hansen, DFL-South St. Paul, said it would be “financially prudent to allow that money to fall to the bottom line” until next year, when the state likely will face a budget deficit. It added that, because the commission didn’t make a recommendation on projects this year, there’s “less agreement and therefore less desire to appropriate the dollars.”

At the root of the dispute is Republicans’ wish to use some of the trust fund money to pay for wastewater infrastructure. GOP legislators say those projects are important to help improve water quality, especially for rural cities facing expensive improvements to aging treatment plants.

“What better way to clean your water than to help these small towns who can't afford funding the whole thing, fixing their pipes now that are 60, 70 and sometimes 80 years old, that are going to start leaching into our ... lakes, rivers and streams?” Ingebrigtsen said in a phone interview last month.

But Democrats and some environmental groups have challenged that idea, saying the trust fund shouldn’t be used for costly infrastructure projects, which are typically paid for with bonding money.

Two years ago, environmental groups sued the state over the use of the trust fund to finance bonds for $98 million in wastewater infrastructure and other projects. Lawmakers eventually agreed to undo what environmental groups called an improper “raid” on the trust fund.

“That’s not what the citizens voted on when they voted on this,” Morse said. “It’s a bait-and-switch to have the constitutional amendment adopted for one set of purposes, and then change it to do what is really a core function of state government.”

The legislative-citizen commission held off on making its usual formal recommendation this year because Ingebrigtsen added $1.5 million for wastewater projects to the list, and some members were opposed.

Hansen, authored a bill in the state House that includes about $64 million for environmental and natural resources projects — but not the wastewater improvements.

What’s at stake

If the Legislature doesn’t pass a bill this year appropriating money from the fund, it will leave dozens of projects without a clear path forward. Some of the proposers said they are worried it would disrupt work that's already underway or cause a gap in research.

The projects at stake include efforts to study algal blooms in Minnesota’s pristine lakes, control invasive species, improve pollinator habitat, protect native prairie, buy land for parks and trails and teach students about the environment.

The Minnesota Invasive Terrestrial Plants and Pest Center at the University of Minnesota is in line for $5 million to fund 15 research projects studying how to manage invasive species such as Palmer amaranth, a fast-growing weed affecting agricultural production across the Midwest.

The Minnesota Zoo is hoping for $489,000 to continue its work rearing native freshwater mussels that will be returned to Minnesota rivers and to educate the public about their importance.

The zoo receives juvenile mussels from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, and raises them so they can be returned to the wild, said Seth Stapleton, the zoo’s director of field conservation.

“Native mussels are ecosystem engineers,” Stapleton said. “They are critical to healthy waterways, with water filtration and habitat creation for wildlife.”

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency is seeking $1.4 million to study and develop strategies to manage per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in treated sewage sludge that’s applied to farm fields, where crops to feed livestock are grown. PFAS are sometimes known as “forever chemicals” because of their tendency not to break down.

“There has been some work done, but there is a lot that we still don't know,” said Summer Streets, a research scientist in the MPCA’s water quality standards unit. “A lot of the dots haven't been connected between PFAS present and biosolids, for example. What happens when you put it on the field, and where does it go and how quickly does it go there?”

U of M professors Lee Penn and Matt Simcik are seeking $425,000 to research tiny pieces of plastic in the environment, and how those microplastics can serve as vehicles to transport other contaminants such as pesticides.

“If we delay these environmental projects, we're delaying a huge number of projects that impact the state in really positive ways,” Penn said.

Lawmakers have until the spring legislative session ends on May 18 to reach a resolution — or not — on the trust fund spending bill.

Ingebrigtsen said if the dollars aren’t spent, they will remain in reserve until next year.

“They have to be spent, and they have to be spent on the environment,” he said. “But it'd be prudent, I think also, just to hang on to it, to see what to see what's going to be needed."

Morse said it doesn’t make sense to hang onto the money until next year because the trust fund is constitutionally protected for natural resources protection, so it can’t be used to fill other holes in the budget.