Legendary Minnesota sports journalist Sid Hartman dies at age 100

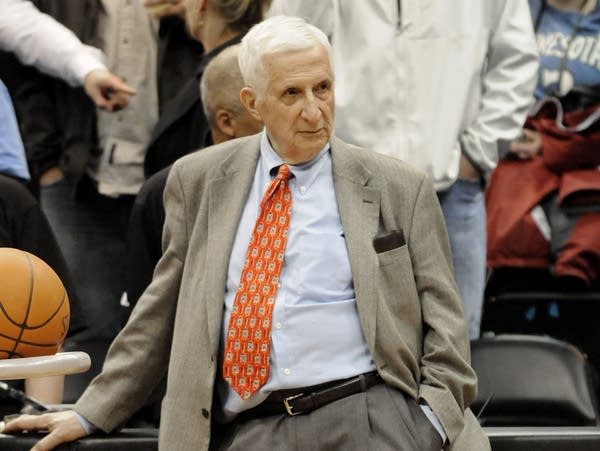

Longtime Minneapolis Star Tribune sports columnist and radio personality Sid Hartman looks on prior to an NBA basketball game in Minneapolis in March 2011. Hartman died at age 100, his family announced Sunday.

Jim Mone | AP 2011

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.