Explainer: Chauvin jurors must disregard defendant's silence

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: April 19, 1:26 p.m. | Posted: April 13, 11:27 a.m.

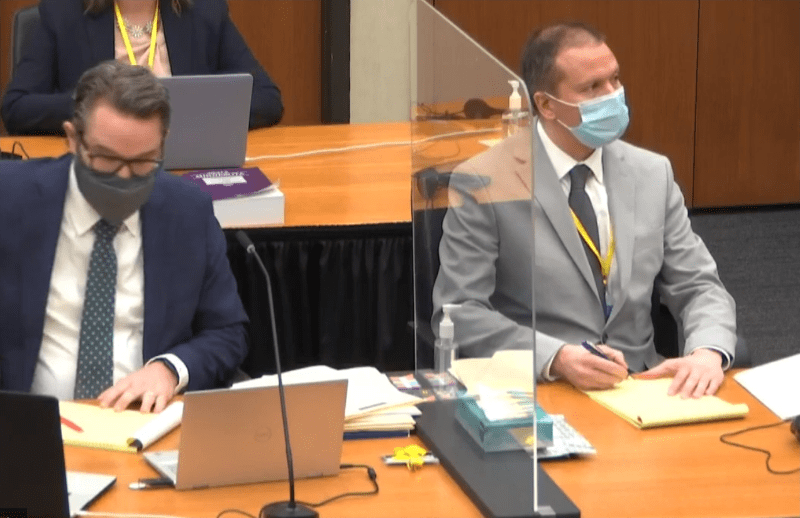

Jurors at the murder trial of the former Minneapolis police officer accused in George Floyd’s death were told Monday that his choice to remain silent cannot affect their decision.

Derek Chauvin on Thursday said he would not to testify in his own defense, invoking his right to remain silent and leave the burden of proof on the state.

It was a high-stakes decision. Taking the stand could have helped humanize Chauvin to jurors who haven't heard from him directly at trial, but it could also have opened him up to a devastating cross-examination.

Legal experts widely agree that jurors often consider a defendant's silence as a sign of guilt, despite the type of instructions that Hennepin County Judge Peter Cahill read aloud Monday before attorneys began their closing arguments.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Chauvin's right not to testify “is guaranteed by the federal and state constitutions,” he said. “You should not draw any inference from the fact that the defendant has not testified in this case."

Chauvin is charged with second- and third-degree murder and manslaughter. Here’s a look at some of the issues that likely went into Chauvin’s decision not to take the stand:

Did jurors want to hear from Chauvin?

Probably, yes.

Cahill questioned Chauvin on Thursday to ensure he understood the ramifications of not testifying, and that the final decision was his and not his attorney's. Chauvin affirmed his decision to remain silent was voluntary.

But legal experts widely agree that many jurors interpret a defendant’s silence as evidence of guilt.

Minnesota defense attorney Mike Brandt said during the trial that he thought jurors would be disappointed if Chauvin didn't take the stand, saying they needed to “hear his explanation of why he did what he did.”

Why might Chauvin have wanted to testify?

Images from bystander video of Chauvin pinning Floyd to the pavement, his face impassive, have been played nearly every day at trial and are likely seared into the minds of many jurors.

The face mask Chauvin has been required to wear in court because of the pandemic has hidden any possible display of emotion by him during testimony. Taking the stand would have given him a chance to explain the video and show another side of himself, maybe giving the jury a reason to convict him only of manslaughter.

"He has nothing to lose, given that that video is so damaging," said Phil Turner, a former federal prosecutor in Chicago, said earlier in the week. "You've got to get up there and give an explanation. It's a no-brainer. You have to."

Multiple witnesses and video evidence have shown Chauvin pinning Floyd for 9 1/2 minutes, well beyond the time Floyd stopped moving and a fellow officer said he could not find a pulse.

Could testifying have hurt Chauvin’s case?

Definitely. Answering sympathetic questions from his own lawyer wouldn't have been a problem. But cross-examination could have been treacherous and increased his odds of conviction on all counts.

“They would be salivating to get him on the stand,” Minnesota defense attorney Mike Brandt said of prosecutors. “They’d have a field day with Chauvin.”

Before Chauvin announced his decision, Brandt said prosecutors could play the bystander video of Chauvin, who is white, pinning Floyd — a Black man — and pausing it every few seconds to ask why he stayed on Floyd.

Arthur Reed, a cousin of Floyd’s who was in the courtroom Thursday, said family members weren’t expecting Chauvin to testify because it “would destroy their case., and that he thinks the state has presented a strong case. He said the family wants the trial to be over.

Was Chauvin likable enough to testify?

Most lawyers want to be sure jurors will like their clients before putting them on the stand, Brandt said, adding that nothing he has seen from Chauvin suggests he would come off as sympathetic.

“Chauvin doesn’t come across as a warm and pleasant person. And jurors want to see a caring and empathetic person. That is the one big liability: If jurors don’t like Chauvin, his fate is sealed,” Brandt said.

Chicago-based attorney Steve Greenberg agreed. If Chauvin rubbed jurors the wrong way, it could have backfired, Greenberg said.

What could Chauvin have said in his defense?

The U.S. Supreme Court has ruled that officers' actions that lead to a suspect’s death can be legal if the officers believed their lives were at risk — even if, in hindsight, they were wrong. And only Chauvin could speak to what he was thinking that day, Turner said.

Chauvin could have told jurors he's not a doctor and couldn't have known Floyd was dying, said Turner. He could have said he kept his knee on Floyd because, from his experience, he knew larger suspects were capable of breaking free and posing a threat.

His lawyer could have had Chauvin testify that he was worried about Floyd’s well-being, and he might have said he wasn't pressing hard on Floyd's neck, despite expert testimony that calculated half his body weight plus gear was on Floyd at least part of the time.

What are the odds he would testify?

Not good. Greenberg said lawyers at murder trials typically don’t want their clients to testify. In more than 100 murder trials at which he represented clients, fewer than 10 took the stand.

“When defendants do testify, it is usually a Hail Mary pass” by a desperate defense that believes it has slim chance of acquittal on any charges, Greenberg said.