Repatriation goes digital: Tribes receive archival copies of cultural materials

Items related to tribal life in North Dakota are being returned digitally.

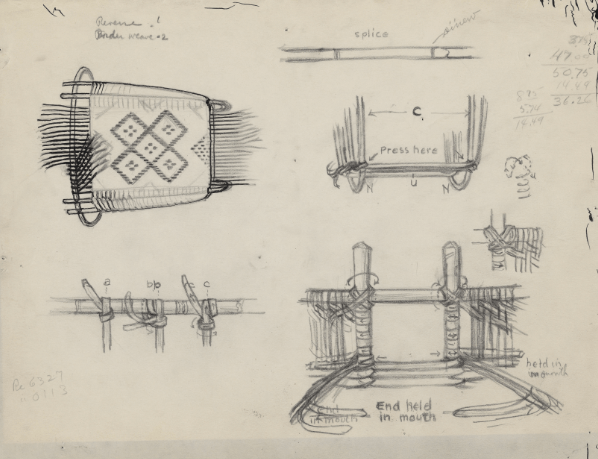

Basketmaking sketch, undated.

Courtesy of the Gilbert L. and Frederick N. Wilson Papers at the Minnesota Historical Society

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.