Minnesota opioid treatment clinics overwhelmed as needs rise, staffs shrink

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Update Dec. 21, 2:50 p.m. | Posted Dec. 19, 4 a.m.

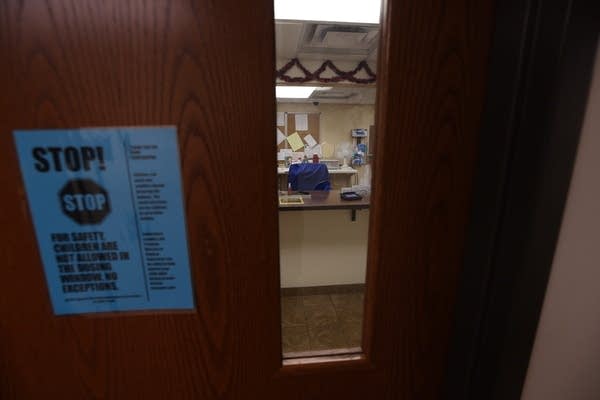

Duluth’s Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment is the only licensed opioid treatment program across Minnesota’s Arrowhead, a territory roughly the size of Massachusetts. Its ClearPath Clinic has space for 475 people; some drive for hours to meet with a counselor or re-up on methadone. It’s a lifeline for those trying to break free of addiction.

Now, though, the clinic is full. About 40 people sit on a waiting list with few alternatives other than waiting and hoping. Even if they could make it to Brainerd, St. Cloud or the Twin Cities for treatment, many clinics are in similar straits — pushed to near or above their limits amid a nationwide opioid crisis.

“We’ve never been overcapacity until this year,” said Jenn Villa, program director at ClearPath Clinic. “We have people dying who are sitting on our waiting list, trying to get in.”

Several of the state’s 16 opioid treatment clinics say they’ve struggled this year to hire and retain licensed drug counselors, but that staff burnout is high and experienced people are leaving for jobs with less pressure and paperwork.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

It’s left many clinics short-staffed and operating over capacity as they try to serve people who desperately want treatment.

State health officials say they’re working on a broad project to reduce administrative burdens on clinics and counselors but caution that it’s premature to point to specific plans.

‘A bad, vicious cycle’

Even before the pandemic put greater strain on health care workers, life as a counselor at an opioid treatment program wasn’t easy.

These particular programs are highly regulated by state and federal guidelines. They rely on licensed counselors who work with patients, adjust dosages and provide comprehensive support.

“On a typical day, a counselor will interact with a nurse, a supervisor, a doctor, they'll collect urine toxicology multiple times and send it to the lab, they’re drawing on blood tests. [If] their patient needs to go to the primary care clinic … they're coordinating primary care follow up,” said Dr. Charles Reznikoff, addiction medicine physician at Hennepin Healthcare in Minneapolis. “It’s very interdisciplinary.”

It’s also high energy, he said. Hennepin Healthcare’s addiction medicine program sees hundreds of patients in its small lobby every day, so there’s a lot of “people contact.”

One counselor can take on a maximum of 50 clients at a treatment program, according to state regulations.

Along with getting labs and charting dosage changes, counselors hold meetings with each of their patients monthly for either one 50-minute session, or four 15-minute sessions. Add charting paperwork on top of that and it’s easy for counselors to get behind.

The job can also be taxing on counselors' mental health.

“We're exposed to a lot of horrible negative things, day in and day out,” said Jesse Inderlee, a licensed clinical supervisor at Alliance wellness clinic in Bloomington. “Whether it's just hearing stories, or whether it's seeing behaviors — I mean, we've had people, you know, getting in shouting matches.”

Survey data from the Minnesota Department of Health found that in 2022, 15 percent of planned exits among alcohol and drug counselors are due to burnout or job dissatisfaction, nearly double from before the pandemic.

“That's pretty striking,” said Teri Fritsma, lead health care workforce analyst at MDH. “Burnout’s essentially causing double the number of losses than would otherwise be the case. And I always think of losses due to burnout as preventable losses, something we could have potentially done something about.”

When counselors leave, clinics aren’t always able to find someone to replace them. Clients are then spread out among other counselors, who must file a variance to the state in order to take on more than 50 patients. But this kind of exception isn’t allowed to accommodate additional patients, and can add stress on staff.

“You can get yourself into a spiral, where you lose a counselor, and then all the rest of the counselors have to compensate for that,” Reznikoff said. “Everybody's work gets harder, people stress out, and then you lose another counselor. And it can get into a really bad, vicious cycle.”

A recent report from the U.S. Government Accountability Office found several barriers to recruiting and retaining behavioral health workers, especially those from diverse backgrounds. They include student loan debt discouraging students from lower-income backgrounds, a lack of training for providers to serve diverse populations and high workloads leading to burnout.

Limited supply and high demand for behavioral health workers may also be leading counselors toward other positions, with less intensive work and higher pay. That makes it more challenging for opioid-treatment programs to attract qualified candidates, especially if they’re outside of the Twin Cities metro area.

Data from the Minnesota Department of Employment and Economic Development shows overall wages for mental health and substance abuse counselors in the state range from $18 to $32 per hour, with a median of about $24 per hour.

“Our rates are fixed, and we don't have the ability to increase the cost of services like other industries do,” said Tina Silverness, CEO of the Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment in Duluth. “That prevents us from being able to pay higher wages and be more competitive with the bigger agencies down in the cities.”

The state’s 16 clinics were operating at 95.7 percent capacity as of Dec. 21. Five are overcapacity, according to state data, and several others are getting close.

That tightening started showing up in the data in the spring, said Eric Grumdahl, an assistant commissioner at the Minnesota Department of Human Services who oversees programs and policies that serve people struggling with substance abuse.

“I would say the crux of [the capacity issue] really stems from just the workforce challenges that we see in terms of recruiting and retaining the skilled workforce needed to operate these programs,” Grumdahl said.

Observers say there are some possible solutions to the problem of hiring and keeping trained counselors, including streamlining paperwork and adjusting meeting requirements so counselors can tailor their approach to individual patients.

They say there’s also a need to boost the number of students getting into the field. Minnesota students can apply for loan forgiveness through the state’s Health Care Loan Forgiveness programs.

State officials say they’re working on opening more clinics. But until that happens, people who want to get off opioids and into treatment may be forced to drive long distances to do so.

“We're five hours from the tip of northern Minnesota, there is no clinic between us and northern Minnesota,” said Villa of the Duluth clinic. “There's no clinic in those areas for people to go to without having to drive a significant distance.”

‘I live with integrity’

Trying to find the staff to meet the needs of patients is frustrating enough, but especially because clinic leaders know that for many people treatment works.

Methadone has been used for decades to treat substance use disorder. The drug, which itself is a synthetic opioid, is highly regulated and taken daily to blunt or block the effects of drugs like heroin and fentanyl while reducing cravings.

It’s one of only three federally-approved drugs used to treat opioid use disorder, but the only one that can solely be provided through an opioid treatment program certified by the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

“When you go to use methadone, it blocks the receptor sites for heroin, opiates, fentanyl,” said Inderlee. “So it tricks your mind into thinking that, you know, you're still getting those other drugs, but you're not. You're getting the methadone, which isn't gonna get you high.”

One of the immediate effects of medication-assisted treatments like methadone is easing withdrawal symptoms, which often resemble influenza — think fever, vomiting, diarrhea — coupled with the return of all the pain that’s been dulled by opioids.

In the beginning, methadone patients come in every day for treatment, and are given limited “take-home” doses — usually just for days when the clinic is closed. The longer a patient is in treatment, the more trust is built and the more take-home doses they can get, though never more than about a month’s worth.

Quitting is a process that happens over time, Inderlee said. For some people it can be a couple of years, for others it can be decades. Some people remain on medication-assisted treatment indefinitely.

“You can stay on it as long as you want,” he said. “What we're looking for, overall, is if the risky behaviors that you were doing aren't happening on the methadone, then that's a win.”

Before treatment, Shawn Victor Wirta described his life as “pure chaos.” His days were focused on getting enough money to get opioids through whatever means necessary, or selling enough drugs to pay off his debts.

“I just didn’t deal with people at all because I more or less looked at people as a disposable resource,” Wirta said. “I remember waking up every day and just not caring if I lived or died, it just really didn't matter.”

Drugs, he said, fueled his paranoia and isolated him from everyone around him, including his daughter. A “really bad car crash” in March 2017 landed him in DWI court, where he was encouraged to go to the Center for Alcohol and Drug Treatment in Duluth, and ask for the help that finally turned things for the better.

“Methadone was the catalyst that allowed me to get the healing that I needed,” he said of his treatments. “It brought me to a place where I think I could feel normal.”

For many people experiencing substance use disorder, medication-assisted treatments such as methadone or buprenorphine can help get their lives back to a place of regularity.

Wirta’s days start early now. He’s up at 5 a.m. to make sure the kids — his daughter, who’s 11, and his girlfriend’s kids, 12 and 3 — are ready and off to school by 7:30 a.m.

He’s been working as a peer recovery support specialist for three years and does regular Zoom meetings with incarcerated people on the path to recovery. Where substance use disorder previously isolated him, it now provides a kind of community.

“[I do] a lot of talking. Like, an obscene amount of talking, texting, I'm constantly on my phone. constantly going from place to place. Dropping off personal hygiene resources or giving someone a ride to a recovery event or recovery meeting, or treatment or doing transport,” he said. “Anything that has anything to do with recovery.”

Where he used to describe his days as chaotic, now he means it in a good way.

“Healthy chaos. I'm consistent. I live with integrity. I'm a hard worker again. I'm an engaged father,” Wirta said. “My life right now looks like normalcy.”

This story is part of Call to Mind, American Public Media and MPR's initiative to foster new conversations about mental health.