The Resurrection Trade

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

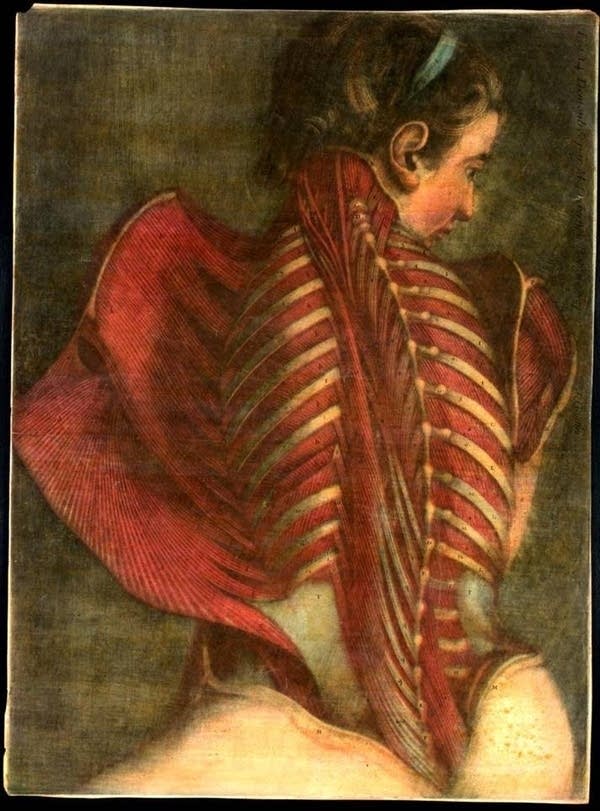

The naked woman on the cover of the "Resurrection Trade" has a Renaissance beauty. Her hair is coifed, and she looks over her shoulder as though to a lover with a demure smile and large eyes.

She's pregnant. And stripped completely of skin.

Leslie Miller says when she saw this image and others, she thought the women had to be real.

"My first reaction to looking at these pictures was to feel skinned myself," she says. "When you look at them it makes your body tingle and cringe because there's no skin on it. And you think about, you feel it viscerally, the skinning. But they also look so vulnerable."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Miller says in the 18th century studying anatomy, and in particular the brain and the womb, was the big thing in science. Trained artists took jobs as anatomical illustrators. They even did the dissection themselves.

Miller says this led to some interesting results. Artists rendered fetuses and genitalia with more beauty than accuracy. Rosy skin and pert breasts were drawn to give the images, an air of life. Prisoners were offered to science, as were the bodies of people who died in poor houses.

Miller was interested in the drawings of women, particularly pregnant women.

"Women died frequently in pregnancy because it wasn't understood what was wrong in there," Miller says. "Naturally, when they died pregnant they were taken apart and these drawings were made. And they were made from real women, in most cases."

Miller's poetry collection is based largely on the images and descriptive text that were used as tools for science.

In the poem "Gautier D'Agoty's Ecorches" she considers the relationship one artist had to his corpses. She links it to a more contemporary reference, that of strung up, flayed rabbit, "still wrapped in its bundle of muscle, like a gift," she writes.

Bodies weren't always gifted to science, though. They were often stolen from graves and sold to anatomy schools. William Burke and William Hare are two infamous Scottish grave robbers.

"They were so successful getting bodies that they finally decided that they could kill someone and bring a really fresh body," Millers says. "And this is really how they were caught, by killing someone in a boarding house where they were staying."

This particular woman was sold to an anatomist named Doctor Knox. He preserved her in whisky until a painter could represent her, and then she was dissected.

"What happened after that was that people got angry with Knox too. Because it was the supply of the medical school that caused these guys to be successful," she says.

Miller says she was struck by the objectification of women's bodies in stories like these, and in the anatomists. She says their air of factualness and objectivity was false. She says doctors believed things like a girl could have blonder hair if she ate the yellow throat tendons of a calf.

All of Miller's hunting around old texts of French anatomists actually began with her own pregnancy. Her son is now four. So she was relieved when, amidst all these artificial and stolen bodies, she read about a French midwife, Madame du Coudray who was hired by the King to teach midwives how to properly birth a child.

"She went all over France for her entire life and trained these illiterate women with this machine she built, basically a model of a woman in labor," she says.

Miller says it was complete with umbilical cord and placenta. She says it saved a lot of lives. Miller says she particularly loved that while male surgeons were developing forceps and hooks to draw out a stillborn baby, du Coudray was teaching female midwives to wash their hands between births, an innovation at the time.

In the course of discovering these models and stories, Miller says realized that defining something removes its purity. She says, really of any subject, once you know what does what and how, the beautiful mystery of it is obscured.