The answer is not that simple

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

If you ask Gov. Tim Pawlenty, his answer would be "No." He said so in his State of the State address in January.

"In too many cases, our high school students are bored, checked-out, coasting, not even vaguely aware of their post-high school plans, if they have any, and they are just marking time," Pawlenty said.

Pawlenty believes that high schools need to modernize to prepare students for the jobs of tomorrow. He describes high schools as a "one-size-fits-all assembly-line model" trying to educate students in a high-tech world.

But the governor isn't talking about gutting high schools and rebuilding them. Rather, Pawlenty wants schools to better prepare students for careers in math and science, and offer tougher classes and more college preparatory courses.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

He said too many students, especially students of color, become disengaged, and then drop out of high school.

Just look at the state's graduation rate -- the percentage of students who earn high school diplomas in four years. Minnesota's graduation rate was 73 percent in 2005, so more than one-quarter of students dropped out or didn't graduate on time.

The numbers for students of color are much worse. The graduation rate for African American students was just 38 percent, and only slightly higher for Hispanic and American Indian students.

While Minnesota's graduation rate has increased slightly over the last few years, nationally, the U.S. has one of the lowest high school graduation rates in the industrialized world.

BILL GATES LEADS THE CHARGE FOR REFORM

"Three out of 10 ninth-graders do not graduate on time," said Microsoft chairman Bill Gates. "Nearly half of all African American and Hispanic ninth graders do not graduate within four years. Of those who do graduate and continue on to college, nearly half have to take remedial courses on material they should have learned in high school."

Gates is one of the leading critics of the American high school. He said the nation's high schools are failing too many students of color, and failing to prepare every student for college. Gates made his case before the U.S. Senate education committee in March.

"Unless we transform the American high school, we'll limit the economic opportunity for millions of Americans. As a nation, we should start with the goal of every child in the United States graduating from high school," Gates said.

Gates is worried about U.S. competitiveness, especially in the areas of math and science. He wants to double the number of science, math and technology graduates in the country by the year 2015.

Gates -- and his money -- drive a lot of the debate over high school reform. The Gates Foundation, which Gates and his wife, Melinda, founded, has an endowment of $33 billion. It has committed to spend $1.7 billion on 1,800 high schools around the country.

Gates goes further than Gov. Pawlenty, wanting to redesign today's large comprehensive high schools, particularly those in urban areas.

Gates' money is building new smaller schools, and dividing big schools into smaller entities within the same building. One wing might focus on technology, another on the arts. Gates believes that high schools with fewer than 600 students are more successful.

"In those high schools, the goal is that every adult knows every student. So that when you're walking the halls, they say, 'Hey, you're supposed to be over there. Hey, I heard you didn't turn your homework in, do you need help?'" Gates told the Senate panel. "If you create a smaller social environment, then it really changes the behavior in the high school."

So are big high schools, those with 2,000 to 3,000 students, the problem?

THE STATE'S LARGEST HIGH SCHOOL

We visited Minnesota's largest high school to find out. Champlin Park High School could be the poster child for the mega high school Gates would like to redesign. It's so big that it takes five lunch periods to feed more than 3,200 students.

Assistant Principal Julie Yager said there's no question Champlin Park is huge. But it also offers amenities that many students want.

She points out the school's gym and weight room for phy ed classes and athletic practices. There's one area for technical classes like woodworking, metals and auto mechanics. The school buses students who want more technical education to a nearby community college.

It also offers Advanced Placement courses, and is in the first year of offering the International Baccalaureate Diploma program, a challenging two-year curriculum designed to broaden students' global understanding.

A couple dozen students dressed in jeans and sweatshirts gathered in the career center to talk about their high school. Many of them said they don't mind the size of the school, because they like the variety of classes and extracurricular activities.

They also like the diversity of the large student body, since it will prepare them for a workforce that's increasingly diverse.

The suburban school is still mostly white. Ten percent of students are African American, another 10 percent are Asian, and fewer than 5 percent are Hispanic and American Indian.

Champlin Park's graduation rate is slightly better than the statewide average, although like the rest of the state, the rate for students of color lags behind the graduation rate for white students.

Like any big high school, it has plenty of cliques. The hip-hop crowd hangs out by the blue lockers, you can find the goth/alternative kids by the red lockers, and the jocks stick together. Freshman Eeva Hyytinen said while there's a lot of drama about cliques, they're not all bad.

"Whether anyone wants to admit it or not, everyone does have some insecurities about coming into a new school, and I think cliques are people's way of trying to find security," Hyytinen said. "It's like their home."

But students admit there's a dark side to cliques. They divide teenagers who used to be friends, and if students get into the wrong crowd, they start skipping school and flunking out. Sometimes, they don't even finish high school.

But cliques aren't the only reason some kids drop out of school. National research shows other factors are teenage pregnancy, drug use, and problems at home.

THESE KIDS ARE ON TRACK

"I know so many people who've dropped out," said sophomore Daysiona Wellner. "And those are people who motivate me to stay in school, personally."

After she graduates, Wellner wants to go to college to study nursing. She knows some dropouts, and the kids she knows aren't doing anything with their lives.

"They're sitting at home talking on the phone all day most of the time, or working at McDonald's flipping burgers!" Wellner laughs. "And I don't want to be like that."

Wellner's mom dropped out of high school at the age of 17 because she was pregnant, and Wellner said her mom would never let her drop out.

Wellner and the other students in the room seem anything but checked out. One student wants to be an accountant, although he's worried about paying for college because his parents are unemployed.

Another wants to be an architect, and is glad Champlin Park offers computer-assisted design classes. One student athlete is applying for a Gates Foundation scholarship to study business.

Still, there's no question that in a school this big, even with all its advantages, some students fall through the cracks. Those are the checked-out kids Gov. Pawlenty refers to. That's why the Gates Foundation is pushing for smaller, focused high schools.

A SMALL SCHOOL WITH A DIFFERENT APPROACH

The Gates Foundation is putting money into schools like Avalon School in St. Paul, a charter school with fewer than 150 high school students. Avalon has received two grants from the Gates Foundation totaling $150,000.

First thing in the morning, Avalon students check in with their advisor. Then they spend their days either working independently on projects, or attending seminars that meet the state's graduation standards. They have individual workspaces that look like office cubicles.

And their projects are certainly different. One student is working on a project about Sicilian cooking for his geography graduation standard. Another student did a project on pop art to meet some of the requirements of her U.S. history grad standard. And another did a project on Star Wars for part of his English grad standard.

The topics sound too quirky to be academically rigorous. But that's why Avalon students get excited about learning, according to Gretchen Sage-Martinson, one of the school's two program coordinators.

Sage-Martinson said Avalon students have to meet the same graduation standards that every Minnesota student needs to graduate. That includes four credits of English and language arts, and three credits each of math, science and social studies. The difference is that Avalon students earn those credits through subjects that are intriguing to them.

"They have to prove that they know every one of those standards," Sage-Martinson said. "Every single project they do, they have to present to two adults -- to two advisors -- and say, 'This is a project I was doing, these are the grad standards I want to get, and this is why I got them."

Sage-Martinson said Avalon doesn't drill students to do well on standardized tests. Yet with the exception of last year's math test scores, Avalon students do better than the state average.

"We tend to emphasize depth over breadth, and so they're digging down and they're wrestling down with some big issues, rather than doing a lot of memorization," said Sage-Martinson.

AVALON 'ROCKS'

So what kind of students thrive in this environment? Sage-Martison said Avalon tends to attract intellectual students who've struggled to do well in traditional high schools.

That was certainly the case for senior Ian Weiland. He's the teenager who did the project on Star Wars. At his old school, Weiland fit the stereotype of the checked-out student. He began high school at a suburban school with about 2,000 students, and he was flunking out.

"It felt like I was just, like, in a prison," Weiland said. "I go from one class, you got five minutes to get to each class, and you'd go there and you'd listen to some boring teacher, pretty much reading out of the textbook. And I'd sit there, and I'd just be so unmotivated and I would just not do anything. I'd just sit there, and I'd just fail."

When Weiland switched to Avalon his junior year, he was four credits behind. But he's catching up, and he hopes to graduate on time this year. In Weiland's opinion, Avalon "rocks." But he said the unconventional school doesn't work for everyone.

"There's some students here, they just sit around and do nothing all day. They acknowledge the fact that they would be better at a standard high school," said Weiland. "You set your own standards, and if you can't meet them, you're gonna fail and you're not gonna graduate."

There are other drawbacks to a smaller, non-traditional school. Avalon doesn't have sports teams, band or choir. One student, an avid photographer, admits she misses the darkroom of her large former high school.

IS SMALLER BETTER?

While smaller high schools are the big push nationally, one education expert says smaller isn't necessarily better. Mike Petrilli is vice president for national programs and policy for the Fordham Foundation, an education policy think tank.

"It makes it much more difficult to have a full offering of extracurricular activities -- sports and drama and theater and the band and all -- and those activities really do add value for young people," Petrilli said.

"The other problem is, it's harder to provide a full core academic curriculum," he said. "If you only have 400 students, you can't afford to hire all the specialists that you would need to teach, for example, physics and chemistry and biology. You might have one science teacher that has to teach all three."

Petrilli said even the Gates Foundation has acknowledged that small schools aren't the panacea for what ails the high school.

"The reason is that so much attention has gone to shrinking the size of schools and making those structural changes, and very little attention has gone to the teaching and learning that happens within those schools," said Petrilli.

"So you might have a school that's more intimate, and that helps to make everybody feel safer and known, and that's a good thing. But if you haven't actually changed what actually happens in the classroom, the teaching and the learning, then you haven't really accomplished much."

PREPARING FOR COLLEGE AT ST. PAUL CENTRAL

When Sarah Clinton-McCausland gets on the bus to school at 6:40 a.m., it's still dark. She's a junior in the International Baccalaureate program at Central High School in St. Paul, enrollment 2,200. Central is the oldest high school in the state.

Clinton-McCausland seems wide awake and energetic, although she said getting up at 5:30 every morning is the worst part of her day.

Clinton-McCausland wishes her classes weren't so crowded, and she thinks inner-city schools need more money. Still, she believes that choosing Central was a good decision, and her advanced classes are training her for college.

"Everyone in them is prepared to go to college, and is learning the kind of skills they'll need for the job they have, which is -- most of the jobs we have are going to be, like, intellectual, not something like being an auto mechanic or cosmotologist or something," Clinton-McCausland said.

Clinton-McCausland is looking at colleges like the University of Chicago and private schools on the East Coast, where she's thinking about studying languages. It's clear that she'll easily graduate and go to college, like both her parents did.

She doesn't know anyone who's dropped out of high school, although the data shows that some of her classmates have. When Clinton-McCausland started Central as a freshman, her class was 600 students. That class has now shrunk to about 500.

Once Clinton-McCausland gets to school, it's time for her first period IB English class. She and her 40 classmates shuffle into their room.

"Hello! Class!"

Teacher Rebecca Bauer raises her voice to get her students' attention. "I know you're all anxious to hang your wonderful images, but I want you to sit down please."

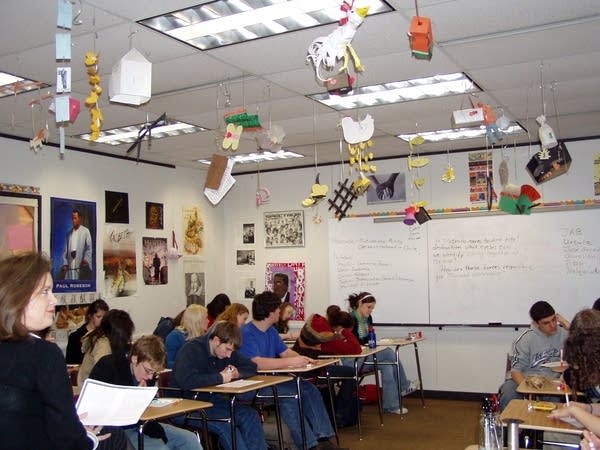

Bauer has asked her students to create images of key details in the novel, "100 Years of Solitude," by Nobel Prize-winning Colombian author Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Paper butterflies, chickens, trains and pigs dangle from the ceiling.

Bauer leads the class in a discussion of some of the novel's themes, ranging from incestuous love to the isolation of humanity. Students talk about why many Americans don't travel outside of this country. One student thinks it's because Americans are too arrogant.

Bauer tells students she thinks technology has resulted in Americans becoming less connected to each other.

"What will be the cost of this kind of solitude?" Bauer asks. One student replies, "People get dumber."

After class, several of Bauer's students stick around to talk about their views on high school. Junior Jesse Mandell-McClinton said some days he likes high school, but other days he'd rather stay home and sleep.

"The thing I don't like about high school is that you have to be here every day, and I'm not the same person every day," Mandell-McClinton said. "And so trying to do the same thing every day the same way, it kind of eats at you, I guess."

Mandell-McClinton said he can't wait to graduate and go to college. Then he thinks he'll have time for all of his other interests, like music and snowboarding.

Bauer said she has plenty of students like Mandell-McClinton who think life will be so much better after high school.

"Their brains are such that they don't always see the long-term consequences of either their actions or what's coming ahead," Bauer said. "So I think you've probably always had kids who are resistant to high school, who feel like they'd rather be sleeping."

Bauer said she works hard to make her classes engaging and relevant, and she changes activities throughout her class periods.

TEENAGE BRAINS ARE STILL DEVELOPING

That's exactly what she should be doing, according to research on the attention span of teenagers.

"Fifteen or 20 minutes is maximum for any high school kid, and for that matter, I find for adults too," said Raleigh Philp, a professor at Pepperdine University who conducts teacher workshops on the teenage brain.

"It's unfair if you think about expecting kids to act at adult levels of organization, skill-making, planning ... before their brains are really finished to do that."

"If you haven't changed the physiological state of the learner in about 20 minutes -- oh, sure, my university grad students will give me paper, pencil, full eye contact -- but the brain is on automatic pilot after about 20 minutes," Philps said.

Philp advises teachers to use a variety of strategies to keep their classes lively, including music. That doesn't mean playing Mozart the entire class. Philp recommends using music as a transition between activities, or during readings.

Philp said research also shows the teenage brain is still developing, and most teenagers are incapable of consistent behavior. He said teens can be loving one day and hostile the next, and they need strong adult mentors more than they ever will again.

"This is a time of tremendous potential for people. And we see kids taking different directions," said Philp. "I guess you could say it's sort of unfair if you think about expecting kids to act at adult levels of organization, skill-making, planning and so on, before their brains are really finished to do that."

So while critics want high schools to be more rigorous and specialized, it may be unrealistic to expect high school students to have their career path figured out.

The Gates Foundation talks about the three R's of high school reform -- Rigor, Relevance and Relationships. That means students need challenging courses, classes that relate to their lives, and adult role models who help them succeed.

It's clear that all of those components can and do happen in many high schools. If you ask teachers, they'll tell you the "relationships" piece of the equation is more likely to happen if class sizes are small.

CLASS SIZE MAY BE MORE IMPORTANT THAN SCHOOL SIZE

There's not much talk about smaller class sizes at the high school level. Policymakers tend to focus on the early grades. That irritates English teacher Brad Johnson from Champlin Park High School. He said high school students aren't checked-out in a class of 20 or 25 students.

"So don't talk about high school size and bigness to me, let's talk about class size," Johnson said. "Where does learning take place? It takes place in a classroom with a number of students that can be adequately taught and be engaged in a reasonable class size. With the budget cuts that have been going on, we have high schools in the Twin Cities area with class sizes over 40."

Johnson blames Gov. Pawlenty's budget for bigger high school classes. And Pawlenty's plan for high school reform doesn't mention class size.

His budget proposal would give high schools an extra $200 per student starting in 2009 if they meet six criteria. Those include rigorous courses, and a requirement that all students take at least one year of post-secondary education while in high school, either college courses or technical education.

When Pawlenty talks about three-R high schools, he means Rigor, Relevance and Results. Pawlenty critics say he's forgotten the relationships piece which is emphasized by the Gates Foundation, and those connections are harder to make if high schools are overcrowded and underfunded.

So is the high school obsolete? Not if schools have teachers who work to keep their classes interesting and innovative, courses that train students for a more competitive economy, and enough teachers, counselors and coaches who won't let students slip through the cracks.

Just ask Stephen Watt, a sophomore at Champlin Park.

"High school's not obsolete!" said Watt. "We're really privileged to go to this school and have such a great teaching staff, and teachers that will work with you if you ask. You just have to step up and ask them, 'I need help,' and they'll do it. 'Cause I've done that plenty of times, and I got my F up to an A and a B."

Watt ticks off the names of a couple of teachers that he said have his back.

So you can create the impact of a small school in a big school setting. But there's also a need for unconventional schools that can work for students who've checked out of traditional high schools.