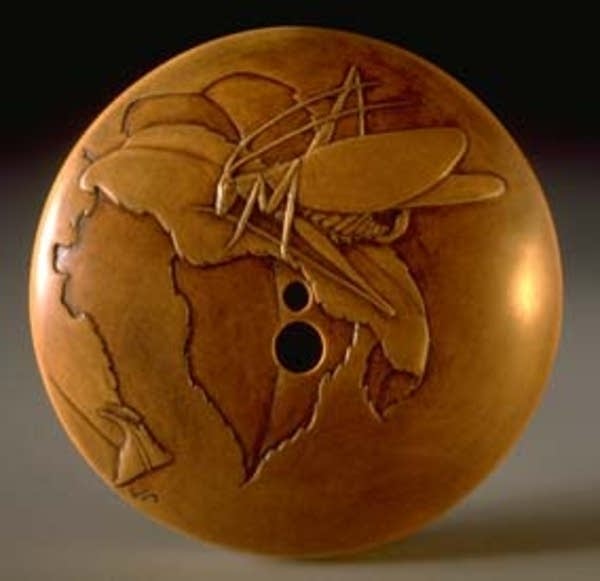

Grand carving on a small scale

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

In a studio, next to a small farmhouse that's not far from the St. Croix River, Janel Jacobson sits at her work bench.

She wears magnifying glasses to help her focus on the piece of mammoth tusk she holds in her hand. She's carved it in the shape of a long bean pod, smooth and incredibly detailed. Only if you look closely will you see a long insect, a walking stick, clinging to its side.

Jacobson's studio looks as though it could belong to a modern-day Charles Darwin. A large old apothecary chest holds her stash of raw materials -- everything from boxwood, mother of pearl and ivory to snakewood, boar's tusk and amber.

Two tree frogs cling to a twig in a terrarium next to her desk, while specimens of moths, butterflies, crickets and cicadas hang from pins stuck into foam boards on the walls.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Jacobson likes to say she does her research on her hands and knees, out in the garden and in the woods.

"There's a lot of activity in a single square foot," says Jacobson. "You'll see the baby insects before they get bigger. You can find snails and wonderful forms. Then at night I like to go out with a flashlight, especially during this time of year when the katydids are just beginning to make their sounds. The snowy tree crickets started this week. You can find them if you're patient."

Jacobson started out as a potter, making creamy porcelain boxes. She etched nature scenes into the lids. As time passed she became more and more focused on the creatures and less interested in the boxes. Frogs and fireflies started to come to life in her hands, demanding to be freed from their two-dimensional world.

It was on a visit to a San Francisco museum that she discovered netsuke, a Japanese style of miniature carving that suited her work perfectly.

At the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, the netsuke expert is Matthew Welch, curator of Japanese and Korean art. In its storage space, the MIA has drawers filled with netsuke -- tiny figures of people and animals, many carved in ivory, others in lacquer or wood. Most are just two or three inches high. Welch says despite their refinement, netsuke's origins are quite practical.

"Netsuke are toggles that were used by Japanese men to secure some kind of pouch to a belt," says Welch. "It could be a pouch for tobacco, it could be some kind of lacquered case for storing medicine, a coin bag. It helped secure that to their 'obi'-- a narrow sash worn by men."

The word "netsuke" literally means "root." Welch says it's believed that the first netsuke were simply interesting knots of wood. But it wasn't long before the Japanese began to articulate these shapes and carve them into detailed forms.

Japanese men began to wear netsuke as a fashion accessory. Someone who was into traditional theater might sport a netsuke made up of masks. A high quality netsuke wasn't just pleasing to look at. It also had to be pleasing to the touch, smooth and unlikely to snag on anything.

Now, while netsuke are no longer practical, approximately 300 people around the world continue to carve them, primarily in Japan. Welch says only a handful of artists attempt to make their living from it. Janel Jacobson is one of them.

"I think the craftspeople who are producing netsuke today are producing astonishing things, and Janel is no exception," says Welch. "The quality of her material is absolutely first-rate. You can imagine that it's a rarefied circle of collectors, and so the standard of quality is quite high and Janel absolutely rises to that standard."

While the work is small in size, contemporary netsuke fetches a big price. Jacobson says many of her pieces sell for several thousand dollars.

But she's quick to point out that in a good year, she might make 10 netsuke. In a slow year, just four. And it's rare that she sells everything she makes.

"I've been to the netsuke conventions seven times and I've sold two, three pieces, so it never pays for itself," she says, then reconsiders. "Well, this year it paid for itself."

To round out her business, Jacobson makes other miniature carvings that don't meet the specialized criteria of netsuke. She also leads an online forum on carving, where people share tips.

She says netsuke is such an unusual art form that she often has to make her own carving tools out of old dental instruments. But to her, it's worth it.

"I get sucked in, I get brought into this world," says Jacobson. "There's just so much to see that's marvelous, remarkable, beautiful in the small scale. It's a way of my giving someone else something wonderful, if they can see it."

Jacobson says her greatest wish is to go to Japan to study. While she has been carving netsuke for close to 20 years, she has yet to visit its birthplace.