Former ICE agent joins firm known for defending immigrants

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

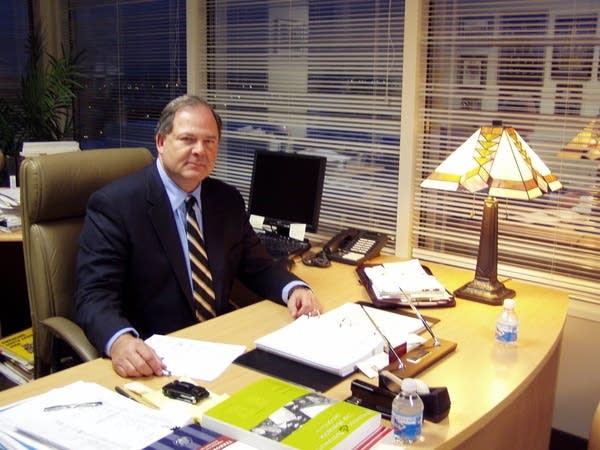

Last year, Mark Cangemi marked the end of a decades-long era: No more undercover operations, busting human smuggling rings, or working the immigration angle of high-profile anti-terrorism cases.

ICE special agents are required to leave the agency at age 57. So Cangemi stepped down from his post overseeing a five-state territory based in the Twin Cities.

Cangemi is a burly guy with a ruddy face and a vast vocabulary that gives him the air of an English professor. He says his first few months of retirement offered a nice respite, but then he got to wondering.

"I had done what I intended to do, and that is do my own personal Thoreau -- read and walk and just reflect," Cangemi says. "And now that I had my first amendment rights back to a degree, I decided well, what am I going to do with this knowledge that I have."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Cangemi's inside view of immigration enforcement left him deeply troubled about U.S. policy. He often felt hamstrung working for government agencies, which, he thought, were never properly funded, but which still got blamed for the nation's burgeoning population of illegal immigrants.

"It was impossible. You got what you paid for. In the end, I think it accomplished exactly what it was designed to do. That was fail," he says.

The first meeting he came to, he made people nervous. He just walked in like a cop, sounded like a cop. I said 'Hey. You're on this side now, okay?'

Cangemi thought there must be a more effective way to deal with the estimated 12 million illegal immigrants in the country. And he thought the way forward might be through helping employers comply with the law, so they are not hiring people they should not.

It turns out Cangemi had an unlikely ally in his thinking. It was one of his previous adversaries, an immigration attorney known for zealously defending the very people Cangemi used to investigate. That lawyer, Herbert Igbanugo, wanted to hire Cangemi to work at his Minneapolis law firm.

"I was at his retirement party last December," Igbanugo recalls, "and I said, 'Hey, are you going to be too chicken to come and talk?'"

Cangemi took the challenge and came to talk. Igbanugo had wanted to build a division in his practice focused on helping employers comply with immigration laws. He too felt that illegal immigration would dwindle if employers actually followed the letter of the law.

And he thought Cangemi was the man to lead the new division. Cangemi had an enforcement background and a law degree. Plus, Igbanugo respected Cangemi's ethics in his years at ICE.

"If there's exculpatory information he'll give it to you, if he sees your client is deserving in some ways, he'll be fair about it," Igbanugo says. "And if he thought your client wasn't deserving, he'd prosecute to the highest extent of the law. I thought that was fair."

So Cangemi and Igbanugo teamed up. They established a strict firewall policy. Cangemi focuses on employers and is kept away from any cases at the firm that could involve people he had investigated.

But as it happens, one of Cangemi's first clients was an immigrant.

Cangemi frequents a restaurant in Woodbury run by Heriberto Herrera. When Herrera learned of Cangemi's legal expertise, he asked Cangemi to do some work for his niece. She needed help with her immigration paperwork.

For people like the Herreras, the last person they would probably think to contact is a former immigration enforcement agent. But Herrera says Cangemi has done well by them.

"So far he's been very helpful and I have a lot of confidence in him," Herrera says.

Herrera has not known Cangemi long enough to be surprised about Cangemi's career switch. But Herbert Igbanugo says the move did initially raise some eyebrows within his own firm.

"The first meeting he came to, he made people nervous," Igbanugo explains. "He just walked in like a cop, sounded like a cop. I said 'Hey. You're on this side now, okay?'"

Cangemi has endured some awkward moments in his new milieu, even outside of Minnesota. He recently attended a conference in Arizona for lawyers in his field. As he sat anonymously in the audience, he had to bite his tongue. A speaker was describing immigration raids Cangemi had led, and was painting a picture of excess force that Cangemi says just never happened.

But Cangemi's confident he and his new colleagues can work harmoniously. Even in his days at ICE, he clung to the principle that people working on opposite sides of a case could arrive at the same conclusion.

"If you ethically represent the interests of government or the client, the outcome should be the same, a fair resolution," he says.

Cangemi's hoping that co-operative spirit might catch on in the broader immigration debate.