'The Counterfeiters' moral dilemma

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

"The Counterfeiters" begins with a man sitting on the beach at Monte Carlo. He's carrying a battered suitcase. His threadbare clothes draw sneers from the staff as he enters the lobby of a grand hotel.

They change to beaming smiles when he opens his suitcase and shows them neat bundles of $100 bills.

What the hoteliers don't know is the bills are fakes, the product of a huge counterfeiting operation in the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. As the film unfolds, the true horror of what happened becomes apparent.

The story has been floating around for years, but Austrian film director Stefan Ruzowitsky says when he learned the Germans forced one of the best forgers of the time to lead the team, it opened up new dramatic possibilities.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"That idea of a counterfeiter in a concentration camp, that sounds great, you know, with all the implications," Ruzowitsky said. "Would he be able to counterfeit, to manipulate reality in the camps?"

The master forger is Solly Sorowitsch, arrested for his crimes, but sent to a concentration camp because he's Jewish.

Sorowitsch survives off his artistic skills, currying favor by painting flattering muscular portraits of his jailers.

When the Nazis set up the counterfeiting workshop at Sachsenhausen, the SS officer who arrested Sorowitsch becomes the commander. He makes sure Solly joins the group.

Director Ruzowitsky says writing the script was a challenge. He wanted to avoid what he calls the cliched portrayals of concentration camp prisoners.

He says he had to dump his first script. When he read it back, he saw how he had -- with the best of intentions -- made each prisoner a noble, educated man.

"This is racism as well, if you say they are so different, even if you say they are better," Ruzowitsky said. "So I tried to show that they are, in every respect, just normal average Germans, and just because of their genes, and their Jewish grandmother, they are bound to die."

Ruzowitsky began exploring the counterfeiters' excruciating moral dilemma. For their work, they get food and normal clothing. They stay alive.

But through the thin wooden walls, they hear other prisoners being beaten and shot elsewhere in the camp. They long for, and fear for, their families.

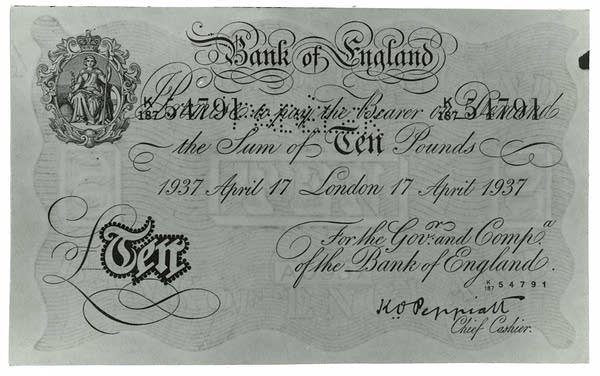

They also know what could happen if they succeed. The Germans want to flood the U.S. and Britain with fake notes, bringing about economic collapse. If that happens the Germans win the war, and counterfeiters will be killed.

So should they cooperate and live another day, or sabotage the operation and die?

"The Counterfeiters" is based on Adolf Burger's book "The Devil's Workshop." He worked as one of the counterfeiters at Sachsenhausen. Burger is in his 90s now, and served as a consultant on the film.

Ruzowitsky says that while Burger was emphatic in the inclusion of certain details, he was willing to be flexible on some issues in the service of getting the story to a larger film audience.

"He always says, 'This is a feature film, it is overall truthful. If you want to learn the facts, read my book,'" said Ruzowitsky. "And that was what I was going for."

Ruzowitsky says the moral issues in the film still echo today, particularly in wealthy and peaceful western countries.

"We know about the misery, poverty, children starving to death in Darfur. As an individual, we don't know how to deal with that either," said Ruzowitsky.

For now Ruzowitsky is enjoying his success, particularly at home in Austria.

He says usually his countrymen don't care much about Austrian films. Opera, theater and classical music are considered the real art.

But then he won the Academy Award. Now he says, he's a national hero, enjoying his 15 minutes of fame.