Age and experience count against older workers

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Case manager Betty Petron works for the Dislocated Workers Program. She's heard the story a hundred times.

An employee works for a company for decades and then one day, they get the news.

"They might get called into a meeting, and they are told you are going to be let go," she said. "Or sometimes, a supervisor stops by their desk and says, 'I need to talk to you.'"

Steven Cross knows how that works.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"Basically it was like, 'Oh, God, what am I going to do now?' kinda thing, because I was 50," said Cross.

Cross lived that story 15 years ago. According to Betty Petron, the rest of Cross' story is just as common.

"Most people look for work the traditional way," she said.

"Basically, I sent out three or four hundred resumes," Cross concurs.

Petron says often workers get frustrated that they are not finding work.

Then comes unemployment compensation benefits to satisfy the financial pressures.

The job search can go on for months and sometimes, like in Cross' case, for years.

Steve Cross knows the feeling and frustration.

"By the end of the year I still hadn't found anything," said Cross.

"I try to hide my age, try to hide the length of my education."

Since 2005, more and more older workers in Minnesota have lost their jobs and once that happens, roughly a third of this group will use up all 26 weeks of unemployment benefits without finding work.

Nationally, it takes workers 55 and up five weeks longer than their younger counterparts to land a job, according to a survey by the AARP.

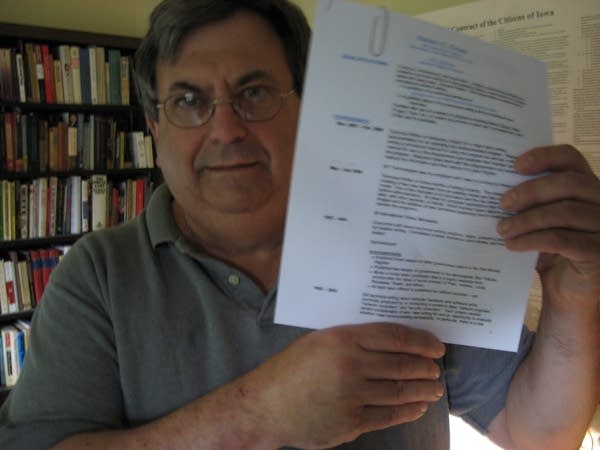

Steven Cross prints up one of the twenty-five versions of his resume he's crafted. Fifteen years later, he's still hunting for a job.

He says at first, he would get interviews and even some temp work. Now, he's lucky if he gets a call back.

Cross thinks it's his age and experience that turns off employers. So, he's started reworking his resume.

"I try to hide my age, try to hide the length of my education," he said. "I got to say that particularly with the education, it just kills me to do it, because I am proud of what I've learned."

At 65, Cross still has a thick shock of dark hair. He's broad and sturdy. Even though he moves a bit slowly, he says he feels young for his age.

But, when he interviews with human resource people in their twenties and thirties, he worries he doesn't look like their co-worker.

"Nobody wants to hire their dad. When I do go in for an interview, I have something of a rule of thumb," Cross said. "If I come in and the person interviewing me is younger than my kids are, I know I'm sunk."

Betty Petron says in a society that prizes youth and beauty, some mature workers have trouble.

The fixation in the workplace on youthful energy she says is something that's especially hard to muster after months of being unemployed. Still, Petron counsels that appearance is worth taking seriously.

"I will even mention to some of the gentlemen, they may want to touch up the hair," she said. "I will talk about, you may want to walk through the stores and see what they are wearing."

Another big issue for these dislocated workers is salary.

Many of Petron's clients had high paying jobs. She tells them it helps to be up front if they are willing to take a pay cut. But even if they are, she says, more often than not, the response is the same: you're over qualified.

That's the bind Damian Martin was in when he lost his executive level job. He hit the streets looking for work, even tried going to a temp agency.

"They had nothing for my level of experience and education," he said. "In the market there was a void for this level of service professionals."

So, Martin started his own company. It's a Bloomington-based firm called Experienced Resources. He pairs up seasoned older workers with companies that need a temporary leader for a special project.

Martin says his goal is to make experience a selling point. In some cases, businesses have said his workers are so efficient that projects finish ahead of schedule. But he still has far more potential workers than he can place.

"Our issue really is not on the talent side. There is plenty of talent out there," he said. "It's having the employer recognize there is a resource like this out there and having employers tap into it."

The odds just might be in Martin's favor.

A recent study by the Minnesota State Demographic Center predicts that over the next 20 years the number of new workers entering the workforce will shrink. If that happens, over looking the older worker may no longer be an option.

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.