The revolution, part 4: 12-year-old experts

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

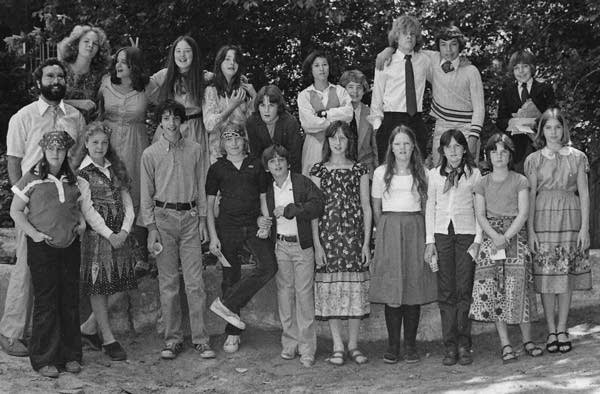

In 1979, 20 middle-schoolers at the Fayerweather Street School, a private school in Cambridge, Mass., wrote "The Kids' Book of Divorce: By, For & About Kids," as a class project. Their teacher, Eric Rofes, got it published in 1981. It was dedicated "to the past, present and future children of divorce."

The book is slim and upbeat, with chapters like, "Separation: It's not the end of the world," and sometimes wry -- there's a chapter on "Weekend Santa." A scrapbook shows they were media darlings for a time, interviewed by Newsweek, The New York Times and 20/20.

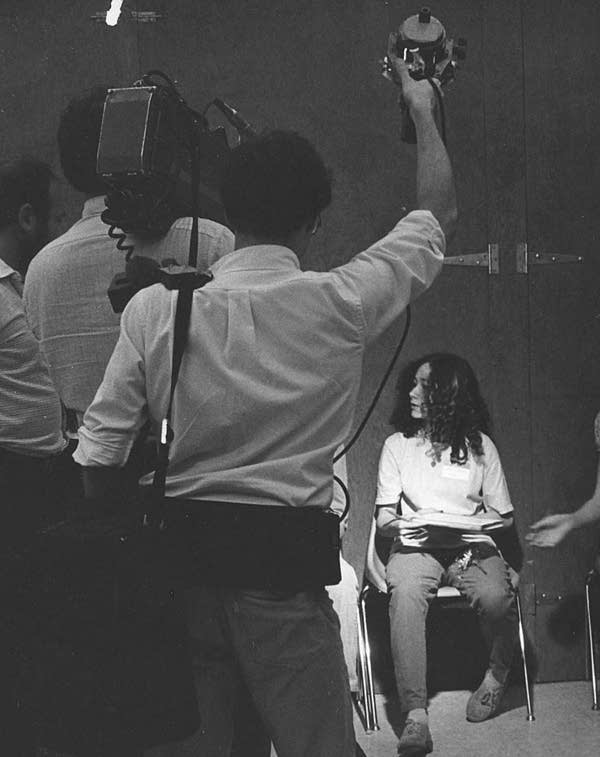

"All of a sudden we were on Donahue, and Today's 4 [on WBZ-TV Boston] as experts, and we were 12 years old," said Louis Crosier, one of the writers.

Crosier and two of his classmates, Hannah Gittleman and Jon Tupta, agreed to come back to the Fayerweather Street School to revisit "The Kids' Book of Divorce."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"What I remember is that halfway through the year, some parent noticed by looking through the Fayerweather phone book that 14 of 20 kids in our class had two households, or some were from single-parent households," said Hannah Gittleman.

Eric Rofes, their teacher, started discussions about different kinds of families, and the project of writing "The Kids Book of Divorce" took off, supplanting the regular curriculum for the rest of the year.

They interviewed adults, like a rabbi who performed "divorce ceremonies." They interviewed other kids about divorce. And they were candid about their own experiences.

Jon Tupta's parents told him they were getting divorced on this 10th birthday. He ended up moving with his mom and two younger brothers far away from all his childhood friends.

Tupta says the "Kids' Book of Divorce" project gave him a place to talk about his family's situation, since there wasn't much opportunity at home. His mom was too busy raising three boys by herself.

Hannah Gittleman and her brother rotated every two months between her mother's house and her father's house. The cast of characters in her life included her mother's boyfriend, stepsisters and boarders.

Louis Crosier lived with his single mom. He watched her struggle to balance work and parenting, and said that hectic time made a lifetime impression on him.

The main point of "The Kids' Book of Divorce" is that it's OK for families to change and be different. That was a new idea then, even if it doesn't sound revolutionary now.

There's practical advice about how life will be different. There are explanations about custody and courts. And there's some surprising wisdom. "Things around the house will probably get lost" is my favorite.

The book concludes that kids of divorce will probably be more careful starting their own relationships. And that prediction seems to have been borne out by this group.

Louis Crosier says when he was younger, he established a pattern of quitting things when life got stressful. It was something he saw his single mom doing -- she was quitting boyfriends and moving apartments every year.

As an adult, Crosier said he made a commitment to hang in there and communicate through the tough times.

"Now with two kids, I'm highly, highly motivated to stay in our marriage. Both because it's a wonderful marriage, but also because I felt very directly the implication of single-parent raising," said Crosier.

The Fayerweather Street School kids wrote in their last chapter: "Another side effect is the pain. Sure, most of the pain is gone by the time a kid is an adult (or a little younger), but some pain is still there. It will always be there."

For Jon Tupta, most of the pain wasn't gone by early adulthood. He was angry.

"It wasn't until I was about 20 that I confronted both my mother and my father about the divorce and what had actually taken place, because I wanted to put it behind me more than anything else so I could kind of go and live my own life without that cloud over my head all the time."

It was a relief for Tupta. He could say to himself, "I don't want to make those mistakes, and I can move on from here because I don't have to repeat their life. I can do something different."

Tupta and his girlfriend have chosen not to marry. They have a son together.

Hannah Gittleman, who had the elaborate two-month rotation with stepsisters and boarders and her mother's boyfriend and the like, kept things simple. A long-term relationship in her 30s that didn't lead to marriage. Then, a first marriage at age 40. No kids.

Gittleman isn't sure how the divorce changed her, and she jokes that it's hard to know how much of their personalities they can blame on their parents' divorces. Researchers have been studying that question.

UNDERSTANDING THE DIVORCE CYCLE

In the 1970s, people weren't sure how divorce would affect kids. Thirty years later, the children of divorce have left a long paper trail.

Nick Wolfinger is a demographer from the University of Utah who pores over giant data sets from the National Survey of Families and Households, tracking children of divorce.

"The bad news is that you really are much more likely to get divorced as an adult if your parents divorced, and parental divorce really does affect almost every aspect of your behavior in your own relationships," said Wolfinger.

Wolfinger's academic book has the ominous title: "Understanding the Divorce Cycle: The Children of Divorce in their Own Marriages." It's like reading a mathematical proof that you're doomed.

"This is why I'm so much fun at weddings," Wolfinger quipped.

When people ask what the bride and groom's chances are, Wolfinger said he cherrypicks the most optimistic data for the happy couple. He does have some advice for the rest of us.

"You really are much more likely to get divorced as an adult if your parents divorced."

"If you want to stay married, marry someone just like you. Except if you're from a divorced family, marry someone from an intact family," said Wolfinger.

That's because Wolfinger found when either the husband or wife was a child of divorce, those marriages were almost twice as likely to dissolve as marriages where neither spouse came from a divorced family.

Marriages between two spouses from divorced families were more than three times as likely to fail. Wolfinger finds children of divorce are more likely to cut and run.

"If you experience relationships as transitory while growing up, that's what you'll do as an adult," he said.

Wolfinger finds children of divorce are about 50 percent more likely to end their own marriages. He breaks down the risk factors that many children of divorce bring into their marriages -- marrying young, not finishing their education, living together first.

The age the child experiences divorce also matters. Wolfinger gives an example of a 4-year-old whose parents divorce.

"Most people remarry, so a couple years later that kid is going to pick up a stepparent," said Wolfinger. "And as you probably know, second marriages have even higher rates of divorce than first marriages, so that kid may experience a second divorce."

By contrast, if a 17-year-old's parents divorce, chances are by the time there's a remarriage, the child is out of the house.

"The age the child initially experiences divorce simply determines exposure to additional family structure transitions," Wolfinger concluded.

Wolfinger looked at how having a stepparent affected kids. Remarriage may make a parent happy, and the family looks nuclear again, but it doesn't undo the damage to kids from divorce.

"You would expect to see good benefits from a stepparent," said Wolfinger.

After all, a stepparent may restore family income to two-parent levels. A stepparent is another adult in the home to provide social control and nurturing. The stepparent might be a role model for a good relationship.

But the bottom line, according to Wolfinger, is having a stepparent makes a kid even more likely to divorce later in life.

Wolfinger thinks having a stepparent shows spouses are replaceable if things don't work out.

Go to: Perfecting divorce, part 1

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.