Community members say they saw warning signs of alleged sex ring

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Even before details of an alleged multi-state prostitution ring came to light this week, a lot of people were worried.

Somali-American members and social workers say they came across a number of warning signs, including brazen solicitations for sex.

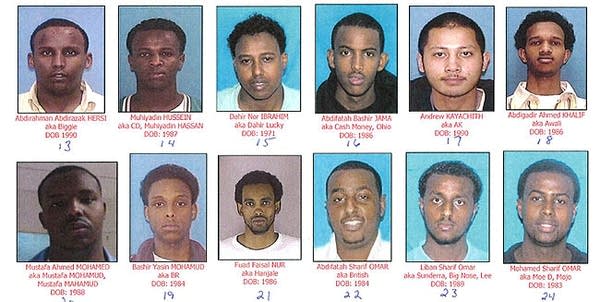

On Monday, federal authorities unsealed an indictment against nearly 30 people, mostly from Minnesota, who authorities say were involved in a sex ring that spanned three states.

Some in Minnesota's Somali community say they hope the arrests will help root out a problem that many considered too touchy -- and too dangerous -- to discuss.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Somali-American community members tell MPR News that pimps have been known to approach men in the parking lots of Somali malls and restaurants in Minneapolis. They say the men would offer young girls for as little as $20.

Abdulkadir Sharif said he couldn't believe his ears when a man at a cafe asked him if he wanted in.

"One person asked me, 'You want a prostitute tonight?' Which sounded really ridiculous to me. I told him, 'You should be ashamed of yourself. To sell our own sisters is not acceptable,'" he said.

Sharif is a reformed gang member who now works for a St. Paul mosque. He said the proposition, done in the open, caught him off guard.

"I was very irritated, and at the same time, I was very shocked," Sharif said.

Sharif said he was involved with the Minneapolis gangs known as the Somali Outlaws and Somali Mafia several years ago, but the groups, at that time, weren't running a prostitution ring. Sharif isn't confident that the authorities netted the right people.

Federal authorities say otherwise. The indictment says over the past decade, the two gangs and their associates, along with a female gang known as the Lady Outlaws, recruited girls and transported them to other states. Some of the girls were younger than 13.

The alleged gang ties to the trafficking ring were not lost on Somali-Americans, and some have stayed quiet for fear of reprisal.

"All I've been hearing is that it's dangerous to talk about it," said journalist Zuhur Ahmed, who hosts a Somali call-in show in Minneapolis on the public radio station KFAI. "People are afraid of what might happen to them, or how they would be hurt, if they talk about it openly."

Ahmed said she had begun researching the issue of teen prostitution in her community a couple of years ago when others urged her to back off.

Now that the case has come to light, Ahmed has begun to delve deeper, and recently hosted a show about the underworld of human trafficking. She says she's heard that some of the clients have been older truckers who take the girls to their next stop, often across state lines.

Those who have familiarity with the trafficking activity said the victims include teen runaways from poor families, who were lured into the ring by promises of cash, cell phones, and clothes -- even food and housing.

Ahmed said that to make matters worse, the girls feel like they can't return home because of the cultural stigma associated with prostitution. Islam forbids sex outside of marriage, and some girls feel that their parents might punish them.

"If some guy messes around with them, that is not only harming the girl but it's harming the whole family and the whole tribe," Ahmed said. "It gets bigger, and I can predict that some girls don't want the issue to get bigger."

Outside of the Somali-American community, social workers say they've tried to sound the alarm about at-risk girls whom they believe might be trapped in the sex-trafficking industry.

Social worker Jan Wenig, who has provided mental-health services for Somali immigrants in the Cedar-Riverside neighborhood of Minneapolis, recalls visiting the home of two teen sisters and their mom. Wenig said the apartment had no bedrooms for the girls to sleep in, and the mother seemed to despise the 13-year-old girl she claimed was her daughter.

But when Wenig was able to speak to the young girl directly, the girl confided in her that the mother was not really her mom, and the other girl in the house was not her sister.

"It was so clear that she was furious at this 'family.' It was clear she had no allegiance to them," Wenig said. "She was a runaway, and they had to bring her back. She was not particularly open to us, either. She didn't know who to trust."

Wenig said she reported the family to child-protection authorities, but the investigation was short-circuited because the girl refused to cooperate. To this day, Wenig doesn't know if the girl was a victim of sex trafficking -- but she does know something was wrong.

Sometimes it takes a crisis to bring cases of human trafficking to the surface, Wenig said, and increased awareness from this week's arrests could go a long way in making girls feel safer to speak out.

Human trafficking is growing in Minnesota, according to those who follow it closely. A recent study commissioned by the Women's Funding Network says the number of underage girls trafficked online rose nearly 65 percent in Minnesota over six months, and some say that figure is indicative of the growth of overall trafficking in the state.

Some of the Somali victims assisted by the St. Paul-based Civil Society came from refugee camps as young girls and were married off to older men, said executive director Linda Miller. After a few years, the husbands either kick them out, or the girls run away.

"When these little girls get thrown out into the community with two kids, they're desperate, they're vulnerable, they don't have good, safe housing, and they are vulnerable to traffickers," she said.

It's not clear whether the girls in the indictment, named only as Jane Does, fit that profile. But one of the girls left the house after an argument with her mother and called Hamdi Ali Osman, who went by the nickname "Boss Lady."

Osman allegedly told the girl "that she would support her, giving her a place to stay and food," according to the indictment.