Volunteers key for independence of aging rural Minnesotans

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

On a recent blustery December morning, Mary Seiler, 56, whizzed around the local grocery store in Frazee, a small town near Detroit Lakes.

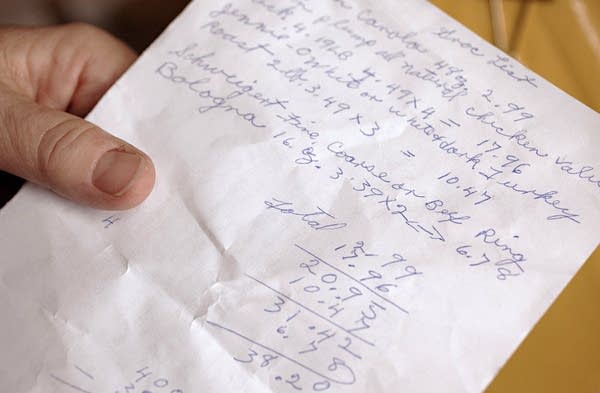

She was shopping for an elderly resident who can't easily get out of the house. Seiler carefully compared prices and looked for bargains, trying to stretch a limited budget.

"This was by far a better deal," Seiler said as she perused packages of chicken in the meat aisle. "I think I'll put that one back because that's not as good a value."

Seiler, a volunteer with Neighbor to Neighbor, delivered the groceries to Selma Hyatt, 75, who lives in a small house in Frazee with her dog Molly.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"I tell her I'm lucky to have her. She helps me with a lot," Hyatt said of Seiler, as she helped her put the groceries away.

AGING COUNTIES

The scene is an example of the quickly aging population in outstate Minnesota -- and how the elderly stay independent. Population estimates released this week by the Census Bureau show rural Minnesota is aging faster than urban areas. The data show that two thirds of Minnesota counties are older than the national average.

Nationally, 13 percent of the population is 65 or older. Two-thirds of Minnesota counties exceed that national average. The 20 oldest counties in Minnesota are all sparsely populated rural counties.

Minnesota Department of Human Services Assistant Commissioner Loren Colman said it's no secret Minnesota is facing a surge of aging baby boomers. For much of the state that surge is 10 to 15 years from now. But in some rural counties it's happening today.

"Some of the counties ... have had to develop programs and strategies," Colman said. "They don't have the luxury of waiting another 15 years."

Another number state officials pay attention to is something called the dependency ratio, the number of people 65 and older for every 100 people of traditional working age. It's a measure of how many people each 100 workers support through taxes for things like social security. It also helps define how many workers will be available to fill jobs in the future. A lower dependency ratio is better.

Nationally, the dependency ratio is 22 elderly to each 100 workers. In many rural Minnesota counties, the rate is twice the national average. Traverse, Aitkin, Big Stone and Lincoln counties all have a dependency ratio higher than 40.

That means many people in rural areas are staying in the workforce longer. It also means there can be a shortage of people to provide services the elderly need.

RELIANCE ON VOLUNTEERS

Minnesota relies heavily on volunteers, family, friends or neighbors to provide those services. Programs like Neighbor to Neighbor in Frazee are critical to helping elderly people stay independent.

Hyatt said the program is the only reason she can stay in her home. The volunteers don't just run errands; Seiler has helped troubleshoot problems for Hyatt that seem insurmountable for someone on a limited fixed income.

"She didn't have hot water and I didn't even know it," Hyatt said. "We found a way to get her a hot water heater. We got her a stove. When her refrigerator went out we found a refrigerator. The mayor put up a gutter over her front door so she wouldn't have ice there all the time."

"Minnesota enjoys a premiere reputation for volunteering ... we have no evidence that's going to change."

Seiler spends between 20 and 40 hours a month picking up groceries or prescriptions, or driving people to medical appointments. She gets paid only in small donations for gas money.

Volunteers can request a small reimbursement for mileage, but most pay for their own gas or take donations from clients, said Neighbor to Neighbor volunteer coordinator Bonnie Julius. She said payment is sometimes very informal.

"They might take someone to Detroit Lakes for a doctor appointment and the client will say, let's stop for lunch. I'll buy you lunch," Julius said.

Neighbor to Neighbor has about 80 volunteers. It can be hard to find enough volunteers, especially in the winter when snowbirds head south for a few months.

"Our service area is six townships and the cities of Frazee and Vergas, so that's a big area to cover," said Neighbor to Neighbor Program Director Sandy Oelfke. "We may have a client on the far end of our area and it's hard to find a volunteer to get there."

The program budget is about $35,000 annually. Last year the volunteers saved an estimated $90,000 in nursing home or related care costs, according to Oelfke. She said it's getting more difficult to find grants to support the volunteer program.

Volunteers are an important part of Minnesota's strategy for weathering the coming surge of baby boomers. Department of Human Services Assistant Commissioner Loren Colman said the demand for volunteers will increase over the next 10 to 15 years.

"I don't know that we know that it's sustainable. It's certainly part of our strategy," Colman said. "Minnesota enjoys a premiere reputation for volunteering. That's part of our heritage and we have no evidence that's going to change."

Census data show the number of people 65 and older will double in the next twenty years. Many will likely become volunteers helping to care for others.

A recent state survey of Minnesota baby boomers found 76 percent plan to spend time volunteering the next decade.

Dependency Ratio in Minnesota Counties