Telemedicine, midlevel practitioners start to fill physician gap

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

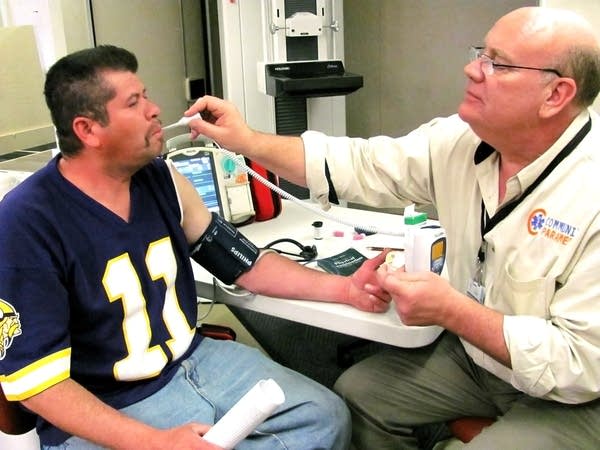

Aboard a semi-truck refashioned to serve as a mobile clinic in Shakopee, Kai Hjermstad takes the temperature and blood pressure of a patient named Jose, who's come in to have his blood sugar tested. Hjermstad asks about Jose's history. Who told him he was diabetic? Does he take medication? Does he have pain in his legs or feet?

This is the sort of questioning usually done by a public health nurse or primary care physician. But Hjermstad is neither of these. He's among Minnesota's first crop of "community paramedics," a new designation for those who have received special training, and can perform an expanded range of services. A medic for 20 years, Hjermstad provides free care to Scott County residents — many without insurance — via the mobile clinic, owned by the Shakopee Mdewakanton Sioux.

When the consultation is over, Hjermstad reviews Jose's case with his on-site supervising physician, Dr. Michael Wilcox, the county's medical director who oversaw the community paramedic pilot training program at Hennepin Technical College. Hjermstad orders a blood sugar test and recommends a referral to a dentist for a bad tooth.

Welcome to the future of rural medicine in Minnesota, where a lack of physicians has opened the door for midlevel practitioners to take on a greater role in providing health care. Community paramedics target underserved rural areas in particular, and efforts are under way to have dental therapists do work once reserved for dentists. At the same time, telemedicine is attacking the shortage from another angle.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The paucity of doctors in outstate Minnesota has become critical. While about 12 percent of the population lives in the state's most rural areas, the Department of Health estimates that fewer than 5 percent of doctors practice there. The primary care doctor-to-patient ratio in Hennepin County is one for every 508 people, according to a recent tally of health rankings. In some rural counties, however, the ratio is closer to one for every 2,000 people. Five rural counties have no primary care providers at all.

TELEMEDICINE A PRACTICAL SOLUTION

Telemedicine is in some ways the most practical solution. It can bring such services as dermatology, endocrinology, pharmacology and even psychology to the far reaches of the state via camera and monitor. Rural hospitals use the technology to fill out their physician rosters and provide specialty care to populations too sparse to support full-time specialists. Patients tend to see remote doctors from the comfort of their regular clinics or hospitals.

Some have wondered whether telemedicine and the use of midlevel practitioners to perform duties previously left to higher-paid doctors, nurses and dentists might lead to degraded care system in rural Minnesota. But at least when it comes to telemental health, patients seem to like it. One recent survey found that 86 percent of patients counseled remotely through a program at the University of Minnesota-Duluth were "very satisfied." In addition, 91 percent of primary care providers called the service "definitely useful."

In fact, telehealth seems to work especially well for mental health care, since counseling doesn't require a physical examination. Often, when a patient in greater Minnesota sits before a camera for a session, the doctor they're talking to is Jane Hovland, a nurse, licensed psychologist, University of Minnesota associate professor and native of north Minnesota. Rural people, says Hovland, "are such a self-reliant bunch." When it comes to mental health, "We expect people to figure it out on their own."

But the fact is, some can't. The most common diagnosis Hovland makes is of major depression, followed by anxiety disorders.

Hovland notes that Minnesota has more psychologists than the national average. But they tend to practice in the city. "There are 13 counties without a single licensed psychologist," she says. "It's a matter of distribution." That's why doctors with the university's telemental health program have seen 2,300 patients over the past five years.

"I had a client who would ride a bicycle in from the woods for telemental health appointments," Hovland says, noting that because the university sees patients quickly, the no-show rate is very low. "We're trying to show that this is a sustainable model," she says.

MIDLEVEL PRACTITIONERS: FILLING THE GAP

Similarly, advocates have high hopes for midlevel practitioners.

The public has largely grown accustomed to treatment by nurse practitioners, specially-trained nurses who can perform physical exams and prescribe medications. But the idea of using midlevel practitioners to fill health care gaps is spreading to other areas of treatment as well.

Minnesota is the first state in the nation to license "dental therapists," who perform duties that fall between those of a dental assistant or hygienist and those of a full-fledged dentist. They can fill cavities and even pull baby teeth, under the supervision of a licensed dentist. Two groups of students are making their way through the state's education systems, one at Metropolitan State University and the other at the University of Minnesota.

"We have a class of nine who will graduate in December," says Karl Self, who directs the University of Minnesota's 28-month dental therapy program. "We believe in one standard of care. For the scope of practice that a dental therapist has that overlaps with that of a dentist, we train our dental and dental therapy students the same. They take the same classes together and take the same competency examinations. We feel this is important to assure the public of the quality of care being delivered."

By design, the students will be deployed to underserved areas, Self says, including rural parts of the state. "We are targeting areas where there is need, where oral health care providers are interested in another option or tool for increasing access." One student, formally a dental assistant in Montevideo, will go back to that practice.

A MINNESOTA EXCLUSIVE: COMMUNITY PARAMEDICS

Minnesota was also the first state to pass a law establishing certification for community paramedics like Hjermstad. The legislation, signed by Gov. Mark Dayton in April, affords these paramedics expanded responsibilities as long as they are supervised by a physician.

A community paramedic might suture a wound, adjust a medication, or address an asthma attack or allergic reaction. They might help a diabetic stay on an even keel or talk through a mental health issue. And here's the greatest divergence from their traditional role: They'll attempt to do it all on the spot, without automatically driving a patient to an emergency room. A community paramedic might even make regular, preventive home visits to "frequent flyers" — those patients who call 911 the most and cost the system dearly.

Driving this new approach, besides a lack of doctors in rural areas, are changes to federal health care law. In the future, Medicare will penalize hospitals for some emergency room re-admissions on the theory that they should be coordinating better outpatient care.

Community paramedicine is a concept that's been popular for years in other countries, such as Canada and Australia, but has only recently made its foray into the United States. "Minnesota is the first state to recognize this with law," says Wilcox. "When you look at the resources in a rural area, there are not enough nurses. Expanding the role of the paramedic in a rural setting, where they can do patient care between 911 dispatch calls, makes sense."

Wilcox and others argue the new law improves care, saves money and preserves rural ambulance services by increasing paramedic fees. Community paramedics could be reimbursed under the state's medical assistance program, though only after study by the state human services commissioner, who must submit a fee schedule to the legislature by January.

"I think the community paramedic legislation is a great opportunity, especially in rural Minnesota," says Mark Schoenbaum, director of the Minnesota Department of Health's Office of Rural Health and Primary Care. "It's an opportunity to use the skills of our rural paramedics who, because they work in isolated and sparsely populated areas, often have time available, to go and perform a variety of services they are qualified and supervised to do."

PUSHBACK BY PROFESSIONAL ORGANIZATIONS, UNIONS

Not everyone supports the increasing use of midlevel practitioners. The Minnesota Dental Association expressed reservations about the state's dental therapy program and insisted on legislative language ensuring monitoring by dentists and other restrictions, though Self says the organization has come around.

And the Minnesota Nurses Association actively opposed the new community paramedic law. While agreeing that healthcare services need to be expanded in rural areas, Carrie Mortrud, the MNA's government affairs and public policy specialist, says, "Creating a brand-new provider is not the answer."

Mortrud is concerned that community paramedics merely replace nurses with cheaper, lesser-trained personnel, at the expense of patient health. "If they would refer and get people into the right system and right care," the MNA would see the benefit, says Mortrud. "If they are going to go in and take over public health nursing, we are not okay with that."

"Paramedics are trained in algorithms," Mortrud adds. "They are trained to respond to what they find on the scene. Nursing is completely different. Nursing is about building a relationship with your patient so you can help them take care of themselves."

Will the use of midlevel practitioners create a second-class health system in rural Minnesota? Not according to Walt Gregg, a senior research fellow at the University of Minnesota's Rural Health Research Center. "It would only be second tier if they were practicing outside a practice scope they are capable of," he says.

Gary Wingrove, program manager of St. Cloud's North Central EMS Institute and chair of the International Roundtable on Community Paramedicine, helped establish the training curriculum. He hopes community paramedics will be just one more member of a patient's healthcare team. "If they find something adverse," Wingrove says, "they will do the assessment such that they can call the primary care provider and talk about the care plan."

"What's kind of happened over time, as medicine has evolved," says Wingrove, "is we've identified gaps in a community that need to be filled. EMS workers already have a skill set that's common in primary care. When there is a hole in the community and the community searches out a way to fill that gap, the best thing they can do is look to existing providers."

"I could easily see 100 paramedics in the state in three to five years," adds Wilcox. "We start a training program at the end of May. We're going to select 24 candidates this time around."

Young paramedics, says Wilcox, "go into it because they like the street work and the adrenaline rush. But that gets old after a while. If you talk to them as they move along in their careers, they want to do more for a patient than load them up and move them along. This is a career path they haven't had available before."

Return to Ground Level: Rural Health »

Dear reader,

Political debates with family or friends can get heated. But what if there was a way to handle them better?

You can learn how to have civil political conversations with our new e-book!

Download our free e-book, Talking Sense: Have Hard Political Conversations, Better, and learn how to talk without the tension.