What's the budget fight about? $1.4 billion and much more

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Republican Senate Majority Leader Amy Koch used this analogy to describe health and human services spending, the major hurdle in budget negotiations with DFL Gov. Mark Dayton:

"What you've got is a 42-inch fridge that we're trying to put through a 36-inch door," Koch said last week.

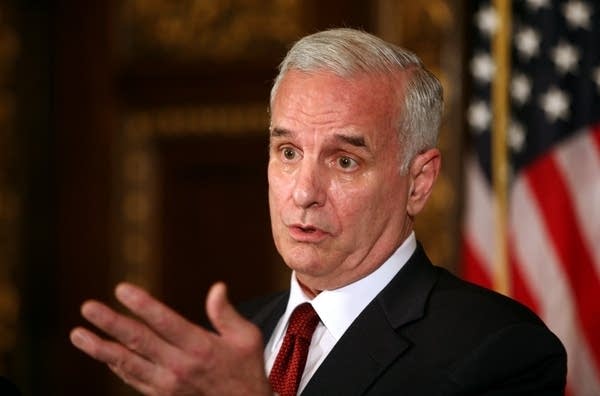

Dayton and Republican legislative leaders can't agree on the size of the refrigerator nor the size of the doorway. That's because they don't even agree on what goes in the fridge.

Policy differences are making the task of solving the state's projected $5 billion budget deficit over the next two years so difficult. That's why the $1.4 billion figure Dayton's administration released last week showing the gap between the governor and the GOP Legislature's budget proposals can't be described only as a matter of dollars and cents.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"I don't think it's as easy as just splitting the difference," said Tim Penny, a former DFL congressman who ran for Minnesota governor as an Independent.

Half of the $1.4 billion could be characterized as differences over how much to spend. For example, Dayton wants to spend $435 million more than the Republicans on aids and credits for local governments, $43 million more for transportation and $10 million more for higher education.

But the other half of the $1.4 billion gap is caught up in policy disagreements over the state's two biggest areas of the budget — K-12 schools and health and human services.

EDUCATION POLICY QUESTIONS COMPLICATE NEGOTIATIONS

Take K-12 education spending, where the two sides seemingly differ on only a few hundred thousand dollars. But Dayton said in reality the disagreements over education policy create a funding gap of $128 million — the Republicans are willing to spend the same amount as Dayton but only when the overall plan includes their policy changes, such as a voucher program for low-income children to transfer to other schools when their public school isn't performing well.

Giving those students money to attend private schools would cost money, but Republicans argue that it would save the state money in the end because per-pupil funding costs more than a voucher. That would allow the state to reduce overall K-12 spending when students leave the public school system.

But those savings also have consequences, Democrats argue. Redirecting funds to private schools would hurt the entire public school system, causing schools to face major cuts from declining enrollment, they said.

Policy differences feeding into the $128 million gap on education also include special education funding (Republicans want limits, Dayton wants steady funding) and school integration aid (Republicans want to eliminate it and redirect the funds, Dayton wants to keep it).

The question is whether it's possible for Dayton and Republicans to compromise not only on the money they're spending on education, but also on what policies should go forward.

"I think they could come up with some of each," Charlie Kyte, executive director of the Minnesota Association of School Administrators, said of the policy differences.

The key would be to do it in a way that makes sense, Kyte said. Penny agreed, using the voucher as an example.

"You'd have to really dig into where the dollars are being spent, because you couldn't really have half the students in a given school building using vouchers and the other half not. You have to think about how that plays out in reality," Penny said.

TOUGH DECISIONS ABOUT WHO TO HELP, AND HOW

Vouchers are also part of the policy disagreements over funding health and human services programs.

Dayton cites a $556 million gap between his and the Republicans' proposal. That difference is largely tangled in the question of how to provide health care to low-income Minnesotans.

Republicans want to get rid of some subsidized health care in favor of vouchers to allow Minnesotans to shop for health insurance in the private market. They also want to change the way health care is delivered to low-income people. Both changes would save the state money.

Dayton wants to continue subsidizing health care for lower income Minnesotans by leveraging federal dollars through an expanded Medical Assistance program, saying people would get better coverage while preventing the emergency room visits that ultimately drive up costs.

Rep. Mary Liz Holberg, a Lakeville Republican who oversees the House Ways and Means Committee, said the voucher program that ended up passing the Legislature was a scaled-back version. It might be able to be scaled back further, she said, but at some point it will cost the state more, making the policy change pointless.

"If we spend more money we have to change the way we're doing things. We're not spending more money to just continually put another step on a ladder of increased spending in the state biennium over biennium over biennium. We're not doing that anymore," Holberg said.

That leaves the state with some tough decisions to make about whom to help and how, she said.

"It's really hard," Holberg said. "It goes to core values."

Rep. Jim Abeler, a Republican from Anoka who heads the House Health and Human Services Finance Committee, said the compromise between Dayton and Republicans on that part of the budget will likely include Dayton's Medical Assistance expansion. It's one of the few things he's made clear he won't give up, Abeler said.

In that case, the way to compromise is by asking the federal government to allow Minnesota to put certain limits on eligibility or control the way the program is run, he said.

"Minnesota deserves flexibility," Abeler said.

But Rep. Tom Huntley, the ranking DFL member on Abeler's committee, said the savings from any flexibility the state is granted likely wouldn't be enough to bridge the $556 million gap between Dayton and Republicans on health and human services spending. Charging health providers more fees could bring the state some revenue to reduce that figure, Huntley said.

"If they go with surcharges on HMOs and health plans, I don't think we're that far apart," he said.

But again, the state must decide the extent of its responsibility to care for low-income and vulnerable residents, and whether part of that responsibility should fall on someone else's shoulders. It's a long-term question that demands an answer now because of the state's fiscal crisis.

Tom Hanson, who served as Gov. Tim Pawlenty's budget commissioner, said if the difference between Dayton and Republicans is $1.4 billion, closing the gap is more complex than figuring out how to end the shutdown and pass a budget.

"It doesn't do [Dayton] a lot of good to build in permanent spending where he's only got one-time spending to pay for it, because he's just going to be back in two years fighting the same battle," Hanson said.