Brothers defend suspect in Minnesota Somalis case

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Two brothers of a former Minneapolis man accused of recruiting fighters for the Somali terrorist group al-Shabab said Monday he's not a terrorist and lacks the mental and emotional capacity to be one.

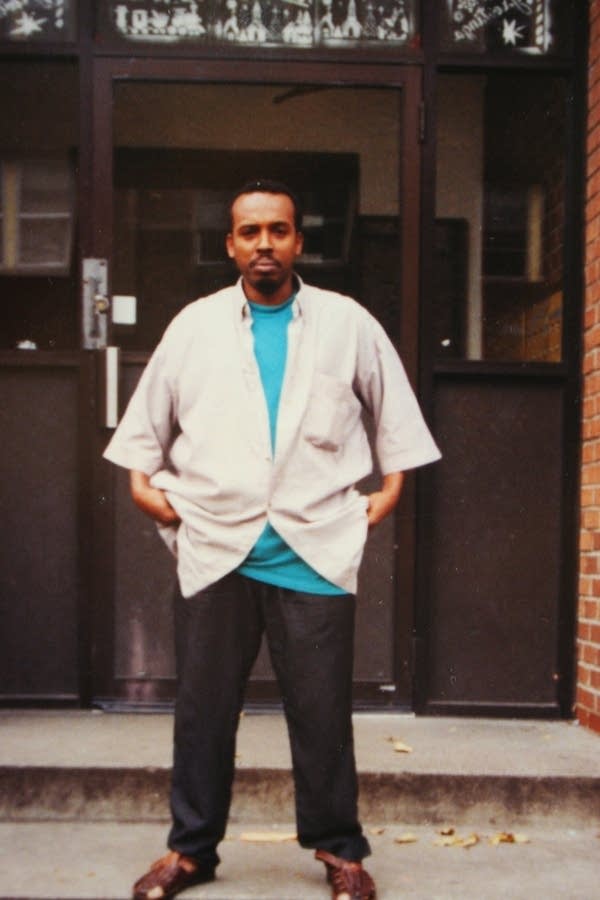

Mohamud Said Omar, 45, made his first appearance in a U.S. courtroom Monday since his extradition from the Netherlands last week. He's accused of helping recruit roughly 20 young men from Minneapolis to fight for al-Shabab and of providing money for the terrorist group to acquire assault rifles.

He has not yet entered a plea on charges of providing material support to foreign terrorists. A federal judge recessed the continued hearing until Aug. 26 to give Omar's attorney more time to prepare arguments for why he should be released pending trial. He will remain in jail at least until then.

Defense attorney Matt Forsgren told the judge he hadn't been able to find a translator who speaks Omar's native dialect, Maay Maay, and that was a significant problem. Forsgren declined to comment on the charges after the hearing but promised, "we'll make sure he's properly and zealously represented."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Two of Omar's brothers, Ahmed Omar and Abullahi Said Omar, both of Minneapolis, attended the hearing and disputed the charges afterward outside the courthouse. Ahmed Omar called them "nonsense," and said his brother will have trouble understanding the proceedings well enough to help with his defense.

He said his brother is dyslexic and has trouble retaining more than a sentence or two of what he's read. He also described his brother as too "shy and timid" to have done the things prosecutors claim.

But the brothers mostly deferred comment to Peter Erlinder, a professor at the William Mitchell College of Law in St. Paul, who said he has worked with the family and Omar's former attorney in the Netherlands for the past two years.

"This guy doesn't have the mental or intellectual capacity to be a leader in anybody's group," Erlinder said.

But Erlinder's role in the case is yet to be determined, and he got off to a rocky start with U.S. District Judge Michael Davis. The professor entered the courtroom as the hearing began, and Davis told everyone to sit down. But Erlinder was still standing when he asked for permission to be heard at some point, and Davis ordered him ejected from the room.

"Take him out. He doesn't understand being seated," said Davis, the chief U.S. district judge for Minnesota.

Forsgren said afterward that he doesn't know Erlinder. He declined to comment further about him.

Outside the courthouse, Erlinder said he was seeking permission to file papers documenting Omar's detention in the Netherlands, where he was arrested at an asylum-seekers center at the U.S. government's request in 2009.

Erlinder said Omar's mental state was already fragile, and deteriorated so much in solitary confinement that he came to believe his Dutch attorney, Bart Stapert, was working for the FBI and fired him. He said Omar stopped calling his relatives and withdrew, and he was unable to focus enough to discuss his case coherently when they met in jail last Friday.

Erlinder also argued the Dutch courts shouldn't have approved Omar's extradition, because most of his alleged acts took place before the State Department designated al-Shabab a terrorist organization with ties to al-Qaida in 2008, and weren't illegal under European law.

The papers Erlinder sought to file included a letter to the judge from one brother, saying a room with the family and his old job in the family store in Minneapolis are waiting for Omar if he's released.

"There must be some terrible mistake here. My brother is a shy, timid guy who can easily be influenced but he has never been a leader in any activity. ... More than likely, he went along with other people because he wanted some friends and to be part of a group," the letter from Abullahi Said Omar said.

(Copyright 2011 The Associated Press.)