For-profit Globe University's recruitment, revenue tactics questioned

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

When a Senate committee led by Democratic U.S. Sen. Tom Harkin of Iowa concluded its two-year investigation of 30 for-profit colleges in July, it issued a harsh assessment of the companies that run them, citing predatory recruiting practices, harassment of students and poor results.

Three Minnesota schools made its list: Capella University, Walden University and Rasmussen College.

The committee couldn't investigate every for-profit school, but Twin-Cities-based Globe University and the Minnesota School of Business, are engaged in similar practices, according to former employees and students of the schools who spoke to MPR News.

Their allegations paint a picture of schools that target students eligible for subsidized loans and grants, but who have low prospects for academic success. They also raise questions about whether students at those schools -- and the taxpayers who subsidize them -- are getting their money's worth.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"I felt like it was just a machine," said Jason Jensen, a former Globe and Minnesota School of Business admissions representative. "It was just all about numbers."

For-profit colleges, which received $32 billion in federal tax money in the 2009-2010 academic year, have catered to millions of students. Globe University and the Minnesota School of Business are a testament to the industry's recent growth.

Though they first opened their doors more than a century ago, in just the last decade the two schools have added 18 of their 20 campuses in Minnesota, Wisconsin and South Dakota. Some are located in commercial areas, such the IDS Center in downtown Minneapolis.

The schools are part of a closely held family business owned and operated by the family of Terry and Kathryn Myhre. Records show they have residences in Stillwater and Naples, Fla. The Myhre family bought Globe in 1972 and the Minnesota School of Business in 1988.

Combined, the schools enroll more than 10,000 students in more than three dozen programs, among them health care, technology and business. They grant certificates, two- and four-year degrees, and some postgraduate degrees, including masters' and doctorate degrees in business.

Tuition and fees vary by program, from $15,000 a year, according to a federal website on post-secondary education. Globe University's website lists costs of more than $45,000 for its two-year health-fitness associate's degree - not including books.

Taxpayers subsidize much of that bill through government-funded financial aid. In the 2010-11 school year, the two schools brought in more than $125 million through federal, state and private grants and loans to students.

Terry Myhre also owns all or part of three affiliated colleges: the Duluth Business University, the Minnesota School of Cosmetology, and the Institute of Production and Recording in Minneapolis. In the same year, those three schools took in more than $17 million in financial aid.

Myhre also owns a majority share of Broadview University in Utah and Idaho, which took in about $20 million in tuition revenue in the fiscal year ending 2011, about three quarters of which came from federal financial aid.

All of the schools promote themselves heavily on TV and in online advertisements. The ads offer no guarantees for a degree or a job, but they suggest students will have opportunities to advance in promising fields.

The ads for Globe and Minnesota School of Business tend to attract a desperate, low-income clientele. Such students are in for a hard, often misleading sales pitch once they contact the schools for information, said the former recruiters and staff, who came forward to expose the schools' tactics.

Such practices were a particular focus of Harkin, chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee.

Globe and Minnesota School of Business may look better than many schools in the Harkin report when it comes to student-loan defaults and reliance on federal money for revenue. But some of the former recruiters' allegations of bad recruitment behavior - such as the harassing phone calls, emotional manipulation and misleading language - read as if they came straight out of the reports on the largest, most aggressive national for-profits.

Former staffers who spoke to MPR News describe a fine-print culture in which the schools regularly obscured important details behind emotionally manipulative sales pitches.

"I fed off of their own shame, their own disgust they had with their own lives," Jensen said.

"I fed off of their own shame, their own disgust they had with their own lives."

Jensen, who worked for the two schools for more than a year, said he was fired in 2011 for not making his recruiting goals. He and other former recruiters say they knew most of the people they enrolled probably wouldn't graduate.

Such students showed little academic aptitude, didn't understand college, or needed prodding and handholding throughout the enrollment process, they said.

Recruiting managers for the two schools knew that, former recruiters said, either through conversations with admissions reps or through their knowledge of students' education records and recruiting interviews. They also say managers ignored their concerns when they told them that a student wasn't ready.

One former online recruiter who spoke to MPR News on the condition that his name not be used for fear of destroying friendships he made at the schools, said some colleagues lamented students' readiness but stopped talking about it once they became managers.

Jensen said recruiters were under pressure to recruit more students, because growing enrollment meant more financial-aid revenue for the schools - regardless of whether students finished their degrees.

This is an example of a Globe University promotional mailer. Story continues below.

The excesses of for-profit college recruiters echo the practices that led to the subprime mortgage crisis, critics of the schools say.

Aggressive marketing convinces consumers to take on huge debt, and, with the help of government subsidies, make an expensive purchase they can't afford. Many may default on their loans, and wind up without the asset they were striving for.

If that occurs, taxpayers get stuck -- directly or indirectly -- with much of the bill. But Globe and Minnesota School of Business executives say they their campuses give people who might not have the chance to pursue traditional colleges a shot at an education.

They say recruiters have to follow scripted presentations to ensure they treat students fairly and give them accurate information. The executives also insist the schools don't allow predatory behavior.

"Our policies are opposed to those things," said Thomas Kosel, the schools' director of government relations. "I think that if any people came to you and told you those things happened - or that they did them - they were unethical, and not part of our policy."

HARASSED PROSPECTIVE STUDENTS

Jensen, the former Globe online admissions representative, said he and about 30 others who sat in cubicles on the company's Richfield campus were under intense pressure. They worked the phones and e-mail system, selling online classes to prospective students.

When someone responded to an ad, Jensen said he would call multiple times a day to keep them on the hook, a frequency he said bordered on harassment.

"We'd just slam them with phone calls, with e-mails," he said. "I had to hit a certain quota of students every quarter to keep my job."

Jensen said company officials expected him to enroll a dozen or more students a term, though quotas varied according to the season.

Globe Chief Operating Officer Jeanne Herrmann said recruiters do receive "goals, and that their jobs could depend on meeting them.

"Their job is to enroll students," Herrmann said. "So after we have worked with them to help them move toward performance in their role, if they're not performing, then yes, they can be terminated."

EMOTIONALLY MANIPULATIVE LANGUAGE

Once online recruiters had prospects on the phone, they would read a questionnaire as part of a scripted presentation designed to learn what prospective students wanted out of life -- from professional and personal dreams to material possessions.

Recruiters would then present a Globe education as the key to achieving those dreams.

But the questions could also dredge up people's frustrations about a dead-end job, or how they struggled to provide for a family. Recruiters were told to exploit those feelings, former recruiter Hannah Von Bank said.

"You're supposed to find the pain that's driving them to go back to school, and use that to get them to enroll," she said.

Globe executives say managers ordered employees to stop using expressions such as "find their pain" in the office about two years ago - about the same time that federal officials were starting to scrutinize for-profit colleges.

MPR has obtained a list of the restricted words.

But the former online recruiter who did not want to be indentified that dropping the sales vocabulary was about changing the school's image, not its culture.

"You know, in trainings they would say, 'We're not going to call them "leads" anymore. We're going to call them "inquiries." Because if anyone caught wind of this, then, you know, it might look like we're in sales. And we don't want them to know we're sales,' " he said.

Globe officials originally told MPR News they didn't know whether recruiters used phrases like "find their pain." But after an MPR News reporter showed them the list of phrases, the officials later said in a written statement that the words "were no longer acceptable."

But former recruiter Von Bank said managers were still using the expression when she worked at the Minnesota School of Business campus in Lakeville, Minn., from mid-May to the late July.

MISLEADING STATEMENTS

The former recruiters say they weren't straightforward with students - and two of them said that their supervisors told them not to be. For example, they avoided detailed discussions of cost.

Recruiters said they held off cost questions and distracted students with other subjects.

But Jensen said recruiters quoted the highest amount of financial aid possible -- even if they weren't sure how much the students would qualify for.

Former employees also say the schools also exaggerated job-placement statistics and starting salaries.

They did that by including Globe and Minnesota School of Business students who worked while going to school. Such students were already employed when they graduated, so the schools counted them as "placed."

One recruiter said they quoted the higher salaries of experienced working students as if they were in the reach of an entry-level worker.

MIXED BAG OF RESULTS

A big question is how Globe and Minnesota School of Business compare to the 30 for-profits mentioned in the Senate report.

Programs at the two schools appear to be more expensive on average, judging from federal data and a comparison of business-degree costs. But a much smaller percentage of their students default on their loans.

On average, the schools appear to be a little less dependent on federal financial aid than those Harkin studied.

However, incomplete federal data makes it tough to compare how well they do at graduating students.

Comparing them to their public counterparts is also difficult. Federal graduation data looks only at first-time, full-time undergraduate students - that is, students who have never taken classes somewhere else.

In the case of the two campuses in the Twin Cities, that means that 90 percent of the students aren't counted when calculating graduation rates. And most of those Globe and Minnesota School of Business campuses are too new to show up in the federal data.

The sliver of data that is available shows only a quarter to half of first-time undergraduates leave with a degree.

Out of every 10 full-time, first-time students who enrolled at Twin-Cities Globe and Minnesota School of Business campuses in 2005, only two to three obtained the credentials they came for, federal data shows.

At Globe's Woodbury campus, the odds were higher; about half did.

Former employees and students say few students understood the demands of college.

"There were students that weren't even at a high-school, weren't even at maybe a middle-school reading level that were being placed in courses."

Many were in their late 20s or early 30s, with families or schedules that offered little time for schoolwork.

Jensen said most of the people he recruited were unemployed -- or working at a dead-end job.

Students at the two Twin Cities campuses are, on average, notably poorer than students at nearby public colleges, given the number of students who receive federal Pell Grants, according to the federally Integrated Postsecondary Education System website.

The former online recruiter who did not want his name used said that the schools' efforts to focus on low-income students bothered him, but many of his colleagues recruited such students.

"We were really focusing on recruiting the bottom-of-the-barrel-type students, the ones that rarely had the means," he said. "Essentially, if you have a heartbeat and you can sign your name, you qualify for Stafford loans."

Federal Stafford student loans and federal Pell Grants are two key ways for-profit colleges make their money.

Stafford Loans are the main federal loans that students use to fund their education. Low-income students also have access to Pell Grants.

This year, for example, a low-income freshman or sophomore could receive up to $11,000 in Pell Grants and Stafford Loans to go to college.

The more of those kinds of students a college enrolls, the more financial aid money comes in.

If students drop out after the five-day drop-add period, they only pay for the classes and days they've attended.

If they stay beyond 60 percent of the term -- about seven weeks -- they're responsible for all of it.

Nick Gerhart, a former student at Minnesota School of Business, recalled studying full time toward an associate's degree in business. He left the school after a couple of quarters of full-time study, with nothing to show for his $12,000. But he was lucky. His father had paid more than half the cost out of his own pocket. The student only had about $5,000 in loans to pay off -- about half the average for Globe and Minnesota School of Business students who take out loans.

According to federal data, in the 2009-2010 school year, more than 70 percent of Globe/MSB's revenues were from federal financial aid money.

Jensen, one of the recruiters, said that made poor students hot prospects - even if recruiters figured they'd never graduate.

"So when we knew we had the single mothers with maybe two or three kids [who] were making minimum wage or not even employed at all, those - those were the ones that, as the rep, we're excited about," he said. "Because we knew they were going to get a ton of money."

Four such instructors said such a recruiting strategy led to the enrollment of unprepared students. They described students who couldn't grasp the math and English concepts necessary for college.

Heidi Weber, a former teacher and dean in the medical-assistant program at Globe said the school allowed low performers into regular classes, even if they needed remedial help.

"There were students that weren't even at a high-school, weren't even at maybe a middle-school reading level that were being placed in courses like anatomy and physiology, pharmacology," Weber said. "And as a teacher, before I was a dean, that's tough to teach those students. Because no matter how much tutoring you do, they're so far behind."

In April, Weber and another former dean filed whistleblower lawsuits in Hennepin County District Court against the company, claiming that the schools engaged in misleading practices.

Herrmann, the chief operation officer, said students must meet minimum academic requirements to enroll. If they score poorly on a placement test, they take remedial classes and get lots of support.

They can still take mainstream classes as long as the remedial courses are not prerequisites to those classes, said Kosel, Globe's director of government relations.

Globe officials also point out their graduation rates aren't worse than many public colleges, and they're even better than some.

But because graduation rates don't include students who transfer out to other schools, public colleges don't receive credit for considerable numbers of students who finish their degrees elsewhere. After transfers are accounted for, community and technical colleges do a noticeably better job than for-profits at fulfilling their mission.

Herrmann said Globe and Minnesota School of Business are designed to teach students career skills -- not transfer them to other schools. But several former students and staff say misunderstandings about transferability of credits were rampant. A former recruiter said many admissions representatives knew many schools typically didn't accept credits from the two schools but wouldn't tell that to students.

Hermann said students sign a statement indicating they understand credits may not transfer. She said recruiters aren't supposed to promise that other schools will accept their credits.

Still, some students and faculty say they heard recruiters make those promises.

Gerhart, of Chapel Hill, N.C., said that that before he enrolled in 2005, he asked admissions representatives whether other schools would accept his credits if he later transferred.

"We were told that they would transfer, no problem," Gerhart said. "They weren't telling the complete story."

Gerhart said that when he transferred out after two quarters, the community college he transferred to accepted none of his credits.

Herrmann said the schools give out accurate information. She said supervisors monitor recruiters to make sure they don't wander from official, scripted presentations.

The schools even send in "secret shoppers" who pose as prospective students to see whether recruiters are sticking to their scripts.

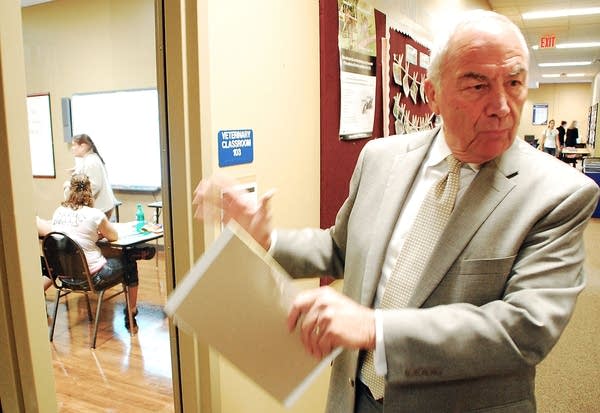

Globe Provost Dave Metzen -- former director of the Minnesota Office of Higher Education -- said recruiters for the two schools are well trained.

"Now if they go rogue, it's not being accepted by anyone in this organization," Metzen said.

But the former recruiters say their supervisors were part of the problem and generally looked the other way when recruiters engaged in unethical behavior.

Former recruiter Von Bank recalls supervisors suggesting tactics:

"People would say, 'You know, off the record, this is what I did when I was an admissions representative that gave me a lot of success. But this is off the record,' " she recalled. "And it would probably be some technique that you shouldn't use or some sort of wording that would be misleading."

Managers themselves pressured recruiters to enroll students they didn't think were ready, Jensen and the unnamed recruiter said.

Jensen recalled telling an indecisive prospective student to explore her interests at a community college first - and then to return to Globe when she knew what she wanted.

"And then when I hung up, my supervisor came up - because he was right next to me - and said, 'What was that?' And I was like, 'She has no idea what she wants to do, and she can't figure it out,' " Jensen said. "And he was like, 'Well, that's your job. You're supposed to tell her what she's supposed to take.' "

STUDENTS KNEW THEY WOULDN'T SURVIVE

Because Globe and Minnesota School of Business are run by a privately held company, it's hard to determine what effect hard-ball recruiting and high dropout rates have on the bottom line.

But higher-education policy professor Kevin Kinser of the State University of New York at Albany said such tactics are part of the business model at a lot of for-profit colleges.

They may find it more profitable to recruit new students, he said, than to spend money on existing students who have little chance of success.

"The reason why you want new students and you don't care about students dropping out, is that it's based on the number of students who are enrolled that you make your money," Kinser said. "So if a student graduates or a student drops out, it doesn't matter as long as you have another student that can replace them - preferably two or three."

The schools, "do not, in any way, practice 'churn.'"

According to federal data, Globe and Minnesota School of Business spend about half what nearby public colleges spend on instruction. Globe spent $2,300 per student in 2010 and Minnesota School of Business spent $2,700 - or less than a quarter of their expenses. Globe officials say that's because they tend to hire part-time faculty, which are less expensive than full-time tenured professors.

That revolving door for students is what for-profit critics such as Harkin call "churn."

But Kosel, the schools' director of government relations, said in a written statement that the schools, "do not, in any way, practice 'churn.' "

This year's allegations of deceptive practices aren't the first. According to court documents, in 1983, a group of people who'd earned diplomas in computer programming from the Minnesota School of Business sued the school.

At the time of the suit, the school was owned by ITT Educational Services, of Carmel, Ind.

The plaintiffs claimed the school made misleading statements about graduates' job placement rates and starting pay.

Later, in 1997, another group of former students from the Minnesota School of Business sports medicine technician program sued the school, claiming it made false and misleading statements about that program.

In each case, the school settled for more than $150,000.