New study shows chemicals can reduce fish survival

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Tiny amounts of chemicals in Minnesota lakes might be having a big effect on some fish populations, according to two new studies by Minnesota researchers.

From the time they hatch, baby fathead minnows have limited chances of survival. Odds are good that they will be eaten by larger fish. But when exposed to drugs, their chances of surviving are worse, said Heiko Schoenfuss, a professor of toxicology at St. Cloud State University.

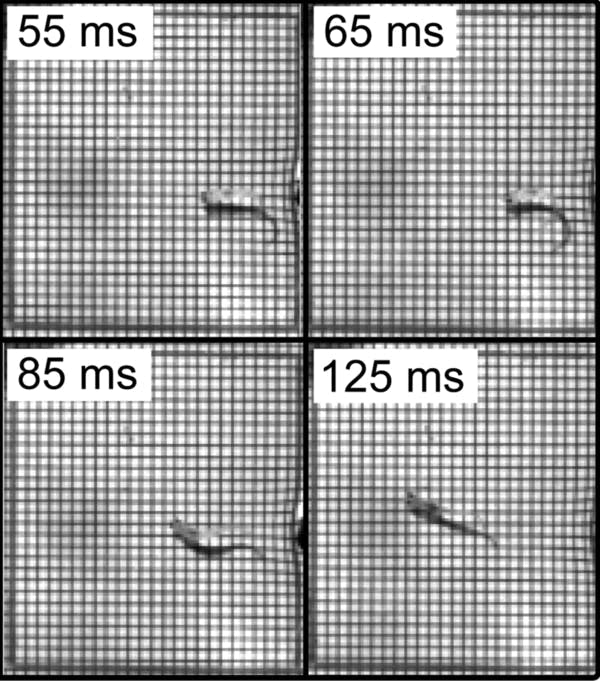

Graduate student Daniel Rearick, who works with Schoenfuss, exposed fathead minnows to pharmaceuticals and estrogen at the same levels documented in Minnesota lakes and compared them with other fish that were not exposed.

"What he found, which is really quite striking, is that fish that were exposed were slower to respond, swam away more slowly than their control counterparts, and as a result of that were more likely be eaten by a predator," Schoenfuss said.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The researchers marked the fish so they could tell them apart. The graduate student then put all the fish into a tank with a predator, a sunfish.

Their results indicate a lower survival rate for the fathead minnows exposed to chemicals. That's an important finding because fathead minnows are a big source of food for predatory sport fish like walleye.

The chemicals could have the same effect on other species said Schoenfuss, who is coordinating his research with U.S. Geological Survey scientist Richard Kiesling.

"Even these very minute concentrations of compounds can have a pretty profound effect on aquatic environments,"

Kiesling, who has been examining how exposure to endocrine disrupting chemicals affects fish reproduction, studied fathead minnows and bluegills. He found exposed fish spawned later and produced fewer eggs than fish not exposed to the chemicals.

Add that conclusion to the finding that exposed young fish are more likely to be eaten and the impact is significant, Kiesling said.

"In an environment where there's such heavy predation those small differences might be enough make a different in population level responses," he said.

In other words it could cause fish populations to drop dramatically. That's what happened a few years ago, when Canadian researchers exposed an entire lake to endocrine disrupting chemicals. The fathead minnow population crashed.

The Canadian scientists weren't sure what caused it.

But the two new studies in Minnesota might help explain why. If fish produce fewer young, and those young are more likely to be eaten, the population will shrink.

However, although researchers appear to have several puzzle pieces that look like they fit together, they still haven't been snapped into place.

Scientists have known for some time that exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals causes adult male fish to develop more pronounced feminine characteristics. Other scientific studies around the world found exposure to traces of endocrine disrupting chemicals can cause fish to become more aggressive.

Monitoring found endocrine disrupting compounds are common in Minnesota rivers and lakes. Most likely come from wastewater treatment plants along rivers, or septic systems near lakes.

Schoenfuss, the St. Cloud professor, said the latest studies show Minnesota lakes are at risk from pharmaceutical and estrogen compounds.

"Even these very minute concentrations of compounds can have a pretty profound effect on aquatic environments," he said. "So just because a lake looks nice and there's still fish in there doesn't necessarily mean this lake is not susceptible to the effects of endocrine disruption."

How big is the risk? Kiesling, a hydrologist and water quality specialist, is trying to answer that question. He is studying Minnesota lakes, trying to determine how much chemical bluegills absorb and how it affects spawning behavior. He hopes to follow fish populations in a lake for several years.

But Kiesling said he believes scientists now have a critical mass of research and there is enough scientific evidence to consider action to protect lakes.

"There's that old saying, 'well, we have to study it more before we move forward,'" he said. " We know that aquatic resources, biotic resources are being affected by these compounds. We certainly have enough information about a number of these chemicals to evaluate if we should move forward with regulatory efforts."

Taking action to safeguard Minnesota lakes is up to regulators and lawmakers, Kiesling said. Meanwhile, scientists will keep trying to define the risk to aquatic life.

Kiesling and Schoenfuss both plan to publish results of their studies later this year.