St. Paul police will reopen child pornography investigation of priest

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

St. Paul police have reopened the investigation into the potential possession of child pornography by the Archdiocese of St. Paul and Minneapolis and one of its priests, a spokesman announced Tuesday afternoon.

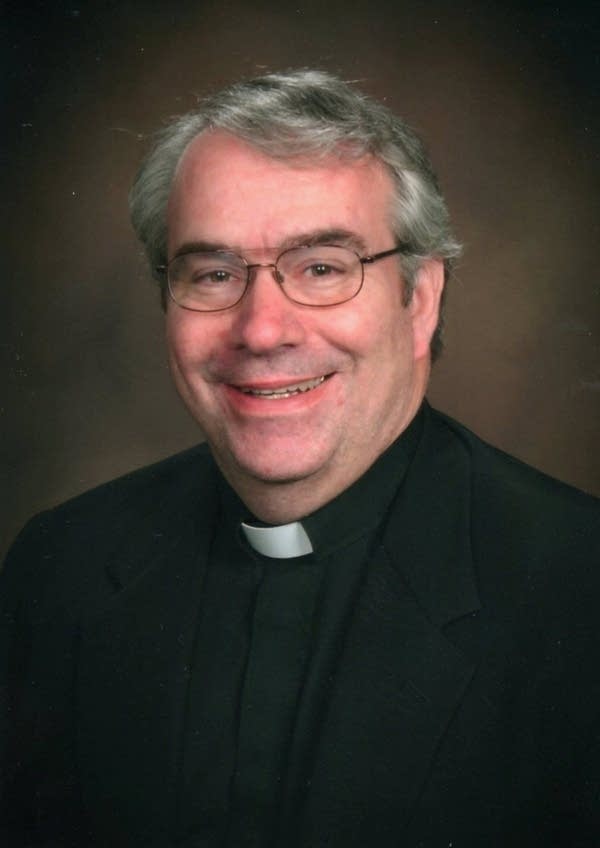

Police had closed the case looking into allegations of child pornography found on computer files once belonging to the Rev. Jonathan Shelley for lack of evidence.

But after receiving several new pieces of information, "today we decided it was imperative that we reopen the investigation," St. Paul police spokesman Howie Padilla said during a news conference at department headquarters.

"It doesn't mean that charges are imminent or that charges are not imminent," Padilla said. "All it means is that we have more questions than we have answers."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The archdiocese released a statement Tuesday afternoon stating,"We will cooperate with any investigation, as we have cooperated since the outset."

Twin Cities Roman Catholic Church leaders have been under fire over their handling of the Shelley case and another involving the Rev. Curtis Wehmeyer.

• Full coverage of the archdiocese investigation

Multiple statements by Archbishop John Nienstedt and archdiocesan officials during the last two weeks have repeated their policy of "zero tolerance" for sexual abuse of children by clergy.

"Our standard is zero tolerance for child abuse by priests and absolute accountability," Nienstedt wrote in a Sept. 27 letter .

However, an MPR News investigation published Sept. 23 found that archdiocesan officials ignored alarms concerning Wehmeyer, and kept secret his attraction to boys. Wehmeyer later pleaded guilty to sexually abusing abusing two brothers, ages 12 and 14, and possessing child pornography.

On Friday and Monday, MPR News published details of an investigation that revealed that two archbishops and at least two vicars general sat on Shelley's pornography collection for about eight years and never informed the police nor followed Vatican procedures, as required by civil and canon law. Memos among archdiocesan officials describe that pornography collection as containing images of boys.

On Thursday, the archdiocese's second in command, the Rev. Peter Laird, resigned his position as vicar general, effective immediately.

Padilla said that the new information included the copy of computer files once belonging to Shelley that St. Paul police received on Friday. Officials from the Ramsey County Attorney's office met with St. Paul police on Monday, Padilla said. He declined to discuss the details of that meeting. John Choi, Ramsey County's top prosecutor, told MPR News two weeks ago that he had concerns with the way church officials handled the Wehmeyer case.

Washington County Attorney Pete Orput vowed last week to follow the evidence wherever it leads.

Padilla declined to say whether police would be investigating the archdiocese for obstruction of justice. He said the current investigation could answer why a search warrant was not executed in the Shelley or Wehmeyer cases.

Police didn't learn of the pornographic images until February of this year, when the former archdiocesan chancellor of canonical affairs, Jennifer Haselberger, reported the images to the Ramsey County Attorney's Office.

She resigned in April due to what she considered immoral practices by her archdiocesan superiors.

While it may be surprising that a case of this magnitude is reopened, it's not unusual, said law professor Eilleen Scallen.

Scallen, who left St. Paul's William Mitchell College of Law to become an associate dean at the University of California, Los Angeles, says the fact that this issue involves the archdiocese plays a factor into the decision.

"There is a very very strong public interest here in making sure that there has been no effort to cover up or protect someone who has involvement in the archdiocese," she said. "So I think that does factor into this."

The initial police investigation found no child pornography and closed on Wednesday. Members of the St. Paul police sex crimes and vice units, however, never received copies of Shelley's pornography collection that internal memos among archdiocesan officials describe as containing images of boys.

Church officials declined to give Sgt. William Gillet the materials he requested when he visited archdiocesan offices in March. Instead, they waited two days before providing three computer disks to police. Even then, however, they refused to give Gillet any documents related to Shelley and his pornography, explaining those were "the product of their investigation."

In a police report he filed Sept. 29, Gillet wondered whether he received all the evidence from the archdiocese.

Church officials also didn't receive all the evidence they requested from Shelley.

Shelley's attorney, Paul Engh, said he had no comment about the fact that the case was reopened.

"I don't have much to add," Engh. "It's hard to comment on what they're going to do."

Engh emphasized, however, that the initial investigation into Shelley found no evidence of child pornography.

The archdiocese first learned of the priest's pornography in 2004 when a parishioner at St. Jude of the Lake received the priest's old computer, found sexually explicit images and reported the discovery to Catholic leaders. Church officials asked Shelley to hand over his other computers for examination. Shelley responded by smashing one computer with a hammer and refusing to turn over another, said Haselberger, who reviewed a report of the examination.

Federal law prohibits "possession of any image of child pornography." Minnesota state law requires priests to report to authorities any indication that a child has been sexually abused within the last three years. Withholding that information is illegal.

And "the Church, and civil law, considers accessing pornographic images of minors to be equivalent to the sexual abuse of a minor," Haselberger wrote to Nienstedt in a memo on Feb. 4, 2012.

Nienstedt drafted a letter - dated May 29, 2012 - to Cardinal William Levada of the Vatican in Rome describing the pornography that contained images of boys, but never sent it. Why is unknown.

In that letter, Nienstedt worries that "the images in [Shelley's] personnel file could expose the Archdiocese, as well as myself, to criminal prosecution."

No one at the archdiocese called police after Haselberger repeated a prior explicit recommendation to turn over all relevant information in the case to law-enforcement authorities. In a memo she wrote Nienstedt on Feb. 8, 2013, Haselberger said the archbishop needed to do that "in the hopes of avoiding prosecution for you and your staff by offering an affirmative defense."

In a separate memo, dated Jan. 27, 2013, the Rev. Kevin McDonough, who headed the Church's child-safety program, wrote Nienstedt that at least four of the images were "quite likely of minors."

He found no need to take further action because "the images themselves were not pornographic, but enticements to take a further step to view pornography" and appeared to be pop-up advertisements. "Were Father Shelley to have clicked on such advertisements, he would likely have been caught in a law-enforcement sting," McDonough wrote.

Outraged that McDonough recommended dropping the Shelley case, Haselberger reminded the archbishop in her memo of last February that McDonough also advised the archdiocese do nothing about Wehmeyer, despite many red flags.

Haselberger also wrote in that memo, "I shared the same images with you and with Father Laird, and neither of you disputed that the images were pornographic."

And, Haselberger wrote, Shelley downloaded images that other internal archdiocesan memos describe as including boys.

A private investigator who analyzed Shelley's computer for the archdiocese found that many of the depictions "could be considered borderline illegal, because of the youthful-looking male image."

That analysis also found that Shelley looked for pornography on the Internet using search terms including, "free naked boy pictures," Haselberger wrote to Nienstedt in a memo on Feb. 4, 2012.

Parishioners throughout the archdiocese learned at Mass last weekend that Nienstedt ordered the formation of a task force to review the church's handling of all cases regarding clergy sexual misconduct.

The archbishop appointed the Rev. Reginald Whitt, a Dominican priest and law professor at the University of St. Thomas, to "oversee the current administration related to clergy misconduct" and appoint the lay task force.

Bob Schwiderski, director of the Minnesota chapter of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), was unimpressed. He called it a smokescreen.

"We've shaken hands with three bishops in the last 12 years who said they'd ask for our side in dealing with priests who have perpetrated sex crimes," he said. "We have yet to hear from them."

Circumstances in the Shelley case changed after Joe Ternus, of Hugo, Minn., gave police files which came from a computer that once belonged to Shelley.

Ternus on Saturday said he contacted St. Paul police to tell them that he made a copy of a large part of Shelley's hard drive before he turned over the computer to the archdiocese.

St. Paul police agreed to review those files and decide whether to reopen a case against him.

Ternus said he's pleased the information was helpful.

"If there's something on there that is actionable, I'm glad it got into the right hands," he said. "I hope they can pursue it to the right end this time."