Prince's death another loss in a decades-long opioid overdose epidemic

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A medical examiner's report released Thursday said Prince Rogers Nelson died of "fentanyl toxicity." The superstar's April death was an accident, the report said; the drug had been self-administered.

Fentanyl is an opioid drug used to treat severe pain. It's more powerful than morphine, and often comes in the form of a skin patch or injection. Its role in Prince's death puts the musician's story at the center of an epidemic that has claimed tens of thousands of lives each year in the United States.

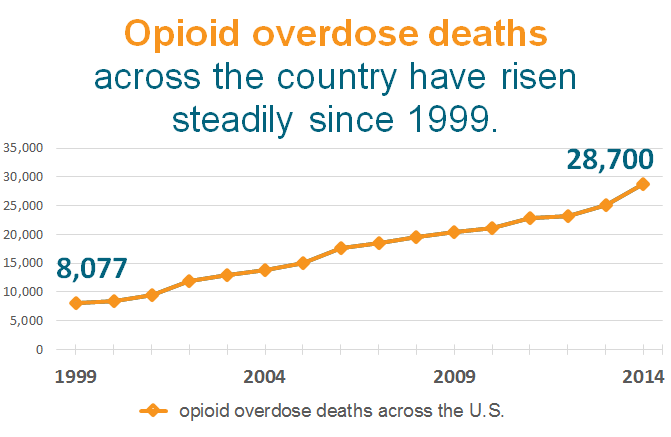

It's a growing problem. Overdose deaths involving opioids, the family of drugs that range from illegal heroin to prescription painkillers like Oxycontin, more than tripled nationwide between 1999 and 2014, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During that same time, the number of people who died of opioid overdose in Minnesota increased fivefold.

Policymakers, public health officials and activists across the state — and the country — are struggling to turn the epidemic around. Just last month, U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar told a group of law enforcement, medical and addiction treatment officials that they need to be part of a multifaceted response to the epidemic.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"We have not solved this problem," Klobuchar said. "We have just started at it."

How did the opioid overdose epidemic begin?

Dr. Andrew Kolodny says much of the blame for the country's surging number of opioid overdose deaths can be assigned to the medical industry. Kolodny is executive director of the national advocacy group Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing.

While opioids have long been used to treat pain, it wasn't until the 1990s that doctors began prescribing them in earnest. Before then, opioid painkillers were prescribed mostly to cancer patients and in end-of-life care.

But Purdue Pharma's 1996 release of OxyContin brought with it a strong marketing push by pharmaceutical companies to get doctors to more aggressively treat pain by using opioids, Kolodny said.

"When it put that drug on the market, it was interested in seeing it prescribed widely," Kolodny said. "The campaign that it launched minimized the risk of opioids as a class of drug, [and] led the medical community to believe that we had been under-prescribing opioids because of an overblown fear of addiction."

Educational efforts and materials produced by drug companies were meant to persuade doctors that the danger of overdose or addiction with opioids was low. Drug companies also promoted the idea that pain could be the "fifth vital sign," suggesting that doctors should use patients' reported level of pain to assess their wellbeing, as they would with body temperature and pulse. A number of high-profile studies reinforced that doctors could successfully treat chronic pain with opioids.

"What the medical community begins to hear is that if you're an enlightened, caring physician in the know, you'll be different from those stingy doctors of the past who were allowing patients to suffer," Kolody said. "You'll understand that opioids can be prescribed liberally and that patients will very rarely get addicted.

"Of course, that was totally untrue."

As late as 2009, a joint statement on pain management by Minnesota's boards of medical practice, nursing and pharmacy implored doctors to provide maximum pain relief — and dismissed the idea that patients could become dependent on the drugs, according to a recent article in Minnesota Medicine, a magazine published by the Minnesota Medical Association.

It's not that the state boards were in the pockets of drug companies or that they had nefarious intentions, said Dr. Steven Waisbren, a surgeon at the Veterans Affairs hospital in Minneapolis — it's just that they were following other national initiatives at the time to try to provide better treatment to patients.

Prescriptions for opioid painkillers are more common in the United States than in other parts of the world. Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world's population but consume about 80 percent of the world's prescription opioids, according to the American Society of Interventional Pain Physicians.

Sales of prescription opioids in the United States quadrupled between 1999-2011, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Prescription opioid overdose deaths and heroin overdose deaths skyrocketed during the same period. Researchers have found some connections between prescription painkiller and heroin abuse. A study published in 2013 found that almost 80 percent of people who began using heroin the year before had previously abused prescription painkillers.

"We have so many Americans on opioids chronically that it's leading to an epidemic of addiction, overdose deaths, rising rates of infants born opioid dependent, outbreaks of infectious diseases, children ending up in the foster care system," Kolodny said. "This is the worst public health crisis that we've had in this country in a long time."

Could changing prescribing protocols help the situation?

The idea that opioids should be used to treat chronic pain is firmly rooted in many doctors' minds, but it has been challenged in recent years.

Now, medical associations across the country — which once touted the importance of treating pain with opioid painkillers — have begun to shift their stances. Just last year, the same three state boards that urged doctors to provide maximum pain relief, reversed course and issued a statement advising doctors to consider alternative ways to manage pain.

This year, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urged doctors for the first time to avoid prescribing opioid painkillers for chronic pain, warning that the risks outweighed the benefits for most people. The guidelines issued by the agency "identified high-risk prescribing practices that have contributed to the overdose epidemic."

What's happening on the legal and legislative fronts?

Klobuchar and Michael Botticelli, who directs the Office of National Drug Control Policy, traveled to Plymouth, Minn., last month to meet with representatives from law enforcement, treatment centers and prescribers.

"We have to be pushing on all of these areas, not only reversing people's overdoses but making sure that they have appropriate access to treatment and that we're preventing it upstream from ever happening in the first place," Botticelli said.

Klobuchar co-authored the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act, which was passed by the U.S. Senate in March. It would expand access to treatment, equip first responders with naloxone — a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose — and help states strengthen prescription drug monitoring programs.

President Barack Obama's 2017 budget proposal would allocate more than $1 billion to expand access to medication and inpatient treatment programs.

About $990 million of that would be set aside for medication-assisted treatment administered through the states. An additional $500 million would be used to bulk up states' drug overdose prevention strategies, improve access to naloxone and support some enforcement activities.

"This idea would be to really bolster the resources for treatment," Klobuchar said last month. "It's a combination of more federal money and state money to treatment, but also making sure that we're enforcing the laws, so the insurance companies are actually offering what they're supposed to be offering."

On the state level, lawmakers recently passed a law that would require doctors and other prescribers to register for the Minnesota Prescription Monitoring Program, which is in place to prevent drug diversion.

The program had been completely voluntary, and only about one-third of doctors in the state even had accounts to log in to its online database. Doctors, dentists and other prescribers still won't be required to check into the system to see if patients have been doctor-shopping, but the bill's sponsors in the Legislature say they're open to more changes next session if prescribers don't start using it.

There have been legislative setbacks for advocates, though, too. In April, President Obama signed into law another bill that would limit the DEA's powers to investigate pharmacies and drug wholesalers suspected of dispensing too many opioids. The law sparked outrage from some doctors and public health advocates, who say it lets the pharmaceutical industry off the hook for their role in contributing to the opioid epidemic.

On the legal front, Purdue Pharma, the company that created OxyContin, agreed to pay about $600 million in fines in 2007 on charges that the company and executives intentionally misled medical professionals and patients about the drug's potential for addiction.

The state of Kentucky settled a similar lawsuit last year for $24 million and cities like Chicago have filed suit against drug companies, too.

How is opioid addiction treated?

As more and more opioid users seek help, treatment centers, too, have begun to shift their approaches. Opioid users now account for about a quarter of all patients enrolled in drug and alcohol treatment programs in the Twin Cities, according to a report released in April by Drug Abuse Dialogues.

Dr. Marvin Seppala, chief medical officer for the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation, said the organization saw a remarkable increase in the number of opioid users entering treatment programs starting in the late 1990s. Opioid users weren't responding to the treatment methods as successfully as patients struggling with other substances.

"They come into treatment and they're abstinent for a period of time. Their tolerance drops. They're at high risk for overdose if they go back to the doses they used to prior to the period of abstinence," Seppala said.

"We started to witness people relapsing after treatment and dying in ways we'd never seen before in terms of pure numbers."

Hazelden Betty Ford programs pioneered 12-step treatment methods, which required abstinence from drugs rather than relying on medications — such as methadone, which also contains opioids — to treat opioid and other addiction. But Seppala said about a quarter of opioid users were dropping out of residential programs early, which he said is often a predictor that they'll have trouble staying clean in the future.

Treatment workers realized they needed to change tactics to help the large numbers of opioid users entering treatment, Seppala said. Three years ago, the Hazelden Betty Ford Foundation began providing medication-assisted treatment at its center. Addicts are given drugs like buprenorphine, which can help patients get off opioids by easing withdrawal symptoms or even making it impossible for a user to get high.

The organization also began putting opioid users into support groups that were separate from the rest of its patients, in order to address the unique challenges opioid addicts face when compared to users of other substances.

"The first thing we do is we educate them through the course of treatment about the risk of relapse and death because of the loss of tolerance," Seppala said.

"Then we do provide naloxone to our patients who have opioid use disorders, because if they do overdose, they may have at least the antidote available for someone else to implement for them."

Those changes have helped opioid users become the least likely patients to drop out of Hazelden Betty Ford's treatment programs, Seppala said. Now only about 5 percent of opioid users drop out of residential programs before completion.

But the move toward providing medication-assisted treatment was controversial in a treatment world that has its roots in traditional 12-step and abstinence-based programs.

"When we first did it, we were vilified by our competitors that had a 12-step abstinence orientation. They thought we were turning our back on our entire heritage," Seppala said. "That's improved, but there's still certainly a schism in the treatment of addiction across the country."

How much does treatment cost?

For many people, treatment is still out of reach: It's expensive. A standard month in an inpatient care facility can range between $5,000 and $30,000. Many insurance plans have high health insurance deductibles that can be difficult to afford.

While federal law requires health insurance plans to cover addiction treatment, that rule hasn't been widely enforced, said Bob Rohret, executive director of the Minnesota Association of Resources for Recovery and Chemical Health. He said cost is a huge hurdle for those seeking treatment.

"Treatment providers oftentimes are limited by who they can accept or how long they can treat someone based on the particular payment source and the restrictions that are inherent in different health plans," Rohret said.

More stories: Opioid overdose — and the families and friends left behind

Opioid users often have a short window during which they're open to treatment. If a spot in a treatment program isn't immediately available during that window, the urge to take opioids to avoid withdrawal symptoms can pull them back into using.

In complex cases where a patient may be struggling with mental health issues as well, Rohret said, the wait for space in a treatment program can often stretch into the weeks or months.

"We're dealing with a population whose executive functioning skills, their ability to plan and think logically and follow up on appointments is impacted by the addiction," Rohret said. "If you hand them a card and say, here's an appointment for next week, they're often not able to follow through with that, or have any significant wait time before they receive care without dropping out of the system."

Many addiction treatment programs have seen the service they provide to patients as distinct and separate from other health care services. And many medical professionals don't know how to treat addiction.

"[Users] cannot walk into a clinic or a health care provider and get the same kind of attention they'd get for any other chronic illness, therefore they fall through the cracks," Rohret said. "The disorders are often seen as personal choices, and the stigmas attached to the disorders themselves prevent them from getting the attention they often require."

Is it possible to stop an overdose?

The opioid overdose epidemic has now claimed so many victims that it's become a talking point on the presidential campaign trail. But even as the number of overdose deaths rose steadily over the past two decades, families often kept the cause of death private, out of obituaries and memorials. They just didn't talk about it.

But now, advocates and doctors — some of whom have been trying to sound the alarm for years — have brought the issue, and its antidote, out from the shadows.

Lexi Reed Holtum and the Steve Rummler Hope Foundation were instrumental in bringing legislation to the state Capitol that expanded the public's access to a drug called naloxone. The medicine can revive someone who has overdosed on an opioid drug. The crusade was personal for Reed Holtum: She lost her fiance, for whom the foundation is named, to an opioid overdose in 2011.

In its most common form, naloxone — also sold under the brand name Narcan — comes in a small clear vial, slightly larger than a bottle of eyedrops. It's become a tool in the fight against opioid overdose across the country.

Until just a few years ago, naloxone was difficult to obtain. It was uncommon enough that even many public health workers struggled to pronounce its name. Some believed it was itself an opioid. But naloxone doesn't get people high and it isn't addictive.

Minnesota was among the first few states to pass a law that would expand public access to naloxone. The legislation allows first responders across the state to carry the medicine. And it made it legal for non-medical personnel to receive the drug without a direct prescription. Perhaps most importantly, it gave limited immunity to users who call 911 to report an overdose.

More stories: Opioid overdose — and the families and friends left behind

"Because of the widespread epidemic across our state, our legislators had a pretty good understanding of the problem," Reed Holtum said. She and others who'd pushed for Steve's Law at the Capitol hoped its passage in 2014 would stem the tide of overdoses in Minnesota. But the reality has been more complicated.

"We came to find out was that, even though you pass a good health and safety law, you really have to work hard toward making sure that you support the state in implementing it," Reed Holtum said. "We're still working really hard to roll that out two years later."

The Steve Rummler Hope Foundation has worked to get state funding for first responders across the state to carry life-saving naloxone, although many have been slow to adopt the policy. They've also worked with hospitals to get it stocked in emergency rooms and have held training everywhere from police departments to living rooms, teaching people how to administer the antidote.

Other allies across the state have focused on getting naloxone into the hands of those most at risk of dying. Adam Fairbanks worked in needle exchanges for years before the passage of Steve's Law.

"We just saw people come in, and then they wouldn't be there anymore, they'd overdosed and died," Fairbanks said. "I just was really passionate in working for those individuals who were lost, and making sure that we could prevent that as much as possible into the future."

Fairbanks ran a program at Valhalla Place, which provides mental health and addiction services, that worked with needle exchanges and treatment facilities across the state to provide naloxone at a low cost. They were able to make inroads in some of Minnesota's hardest-hit, including on some tribal lands, where the rate of opioid overdose deaths is sky-high.

"We really focused on getting naloxone into the hands of the people at highest risk, so: drug users themselves," Fairbanks said. "We also really were aggressive about it, getting a large amount of naloxone out into the community for people who truly need it."

That program alone last year led to a reported 197 opioid overdose reversals. Advocates say the true number is probably much higher, because many reversals aren't reported.

While some progress has been made, Fairbanks said the need for more access to naloxone is still high in rural areas, where medical assistance can be a long drive away. Despite all the work, government data shows that opioid overdose deaths are still rising in Minnesota and across the country.

"It is absolutely heartbreaking and devastating that we aren't farther," Reed Holtum said. "And I know that everybody is doing the best they can, but it takes a while to reverse an epidemic."