Fitzgerald didn't satisfy this author, so she wrote her own 'Gatsby'-inspired novel

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

F. Scott Fitzgerald's beloved American novel The Great Gatsby is about the messiness of chasing the American dream. But author Stephanie Powell Watts says something about the book left her unsatisfied.

"I loved it when I was a kid and read it for the first time. ... But subsequent readings, I felt like I'm seeing other things. I'm seeing all of these black characters — never thought about them before. I'm seeing the women and the tiny, tiny roles that they have in the book, and I want them to speak. I want to hear what they have to say."

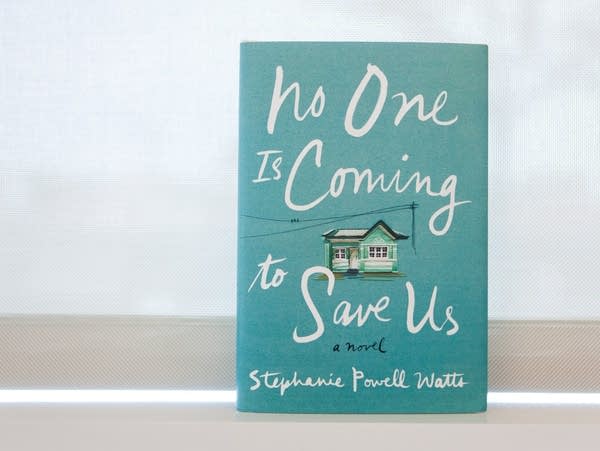

According to Watts, the only way to do that was to "make them say it," so she wrote her own novel. No One Is Coming to Save Us isn't exactly a retelling of The Great Gatsby; instead, Watts uses some of the same themes to tell a story about black characters in a declining furniture town in present-day North Carolina. Her stand-in for Jay Gatsby is JJ Ferguson, a man who returns home wealthy after 17 years away.

Interview Highlights

On how much her book relates to The Great Gatsby The kernel, the seed of the book is very much in the spirit of Gatsby: the idea that someone returns to a place that is home for him, or he's hoping is home for him, and he comes back and he is hoping to live out a fantasy life that he's dreamed about for some time. And so that kernel to me is what my book is about, or is at least a starting place for my book. But it goes in different directions from there. On JJ's belief that you never get over being poor

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

This is actually something that my father says: "Poor people never get over it." He is quoting from my father ... [who] says it from experience. And I don't think that you do. I mean, I'm many years from the time when I was worried that my car might not make it somewhere, or something like that, but I still remember the sting of that. I still remember the tears at the back of my throat from that, you know. And I think it's very, very difficult to get over it. And I think that that's what Jay Gatsby has experienced, and I think that's what a lot of my characters experienced, too.

On deciding to make so many of her central characters women When you read Gatsby, or maybe even shortly afterwards, didn't you want to know about Daisy? I mean, she's so flighty and she seems so ridiculous, there has to be something in there that's making her make this tremendous move in her life. Or Myrtle — I mean, she's so much like Jay Gatsby, you know: She's such a striver; she's trying so hard to you know "better herself"; she's trying so hard to be in another class.

And so those kinds of questions made me think about, "Well, what about these women here?" I want to talk about the ones that are like my mother and like my grandmothers, who are striving and trying to figure out the world with not a whole lot of resources in all kinds of ways, but who want better for themselves and for their children. And so I'm really drawn to those characters that don't get their say.

On writing: "Children need old people. ... Old people can tell us what they know about the past. ... Thank God the old tell it slant so the jagged edges don't kill the babies."

There are a number of stories that I feel like we're told in particular ways. My grandfather used to tell a story about being beaten up as he was walking home. And two white men stopped him on the road and called him the N-word and said that they would get out of their truck and beat him up. ... He's telling the story to the family and this story is so horrible, but he's laughing about it. He's telling, you know, he said, "No, I don't think you'll get out of that truck." And, you know, his hands are on his hips. And he says they do get out of the truck and they beat him up.

And for a long time I could not see that story as a triumphant story because I could just see him there on the ground having been beaten. But he changed the story and he became heroic in the story, and his telling of it and just the fact of his telling of it made it a triumph. And he's laughing at them — they're the boobs in the story, they're the ones who couldn't figure things out. For a long time I did not get and I couldn't find any humor or any triumph in it, but I have now. He did, he did win. He did get the best of that story. And it's a hard story, but it's one I'm really glad I have.

On whether she ever finds herself sanding down the jagged edges of her own stories

Oh yes. I was telling a story to my son and we were coloring together — this was about crayons. And I told him that when I was a kid I so wanted this box of crayons, the 64 crayons. They were so beautiful, such exotic, wonderful names and I really wanted them but I didn't get them. We couldn't afford them.

Later on in the day, when I thought he'd forgotten all about it, he brings me 64 of his own crayons and he says, "Mama, I have 64 crayons for you." I was blown away by it. It was so touching to me, but also that he wanted to make that story right for me. He wanted to make that good, and he could do it. It was in his power to do it and he did. And so now when I think about that story that might have been a story about poverty or might have been a story about deprivation, it's now a story about my lovely sweet son and that story is right beside the other story. But I'm nervous about it. You know, I don't want to tell him so much that it wounds him or that he feels responsible for my pain. So it's a real balance that I'm kind of doing all the time.

Radio producer Sam Gringlas, radio editor Ed McNulty and digital producer Nicole Cohen contributed to this story. Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.