Southern cooking: 'People of color didn't get the respect they earned'

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

John T. Edge is a man who knows how spin a good yarn. Listening to him talk can feel like falling under the spell of your favorite college professor. He's wickedly smart, funny, warm and welcoming.

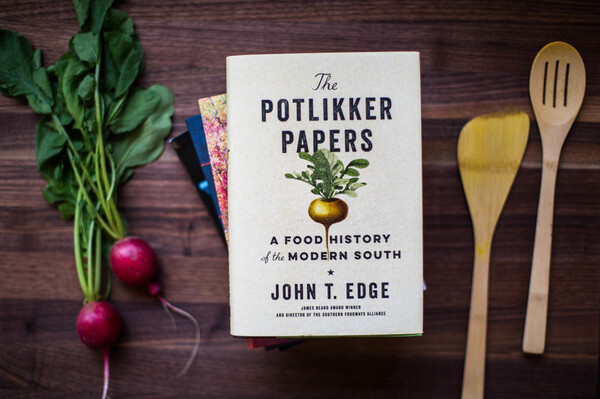

And for years, the tale he's been telling is all about Southern food: about its central role in Southern identity, and about what it owes to the African-American and immigrant cooks who have historically been left out of the standard narratives the South tells about itself. In his new book, The Potlikker Papers: A Food History of the Modern South, Edge attempts to pay down what he calls "a debt of pleasure to those farmers and cooks who came before me, many of whom have been lost to history."

"These were women, these were often times people of color who didn't get the respect they definitely earned," Edge says. "And in paying down that debt of pleasure, I hope to bring their lives into relief and make explicit the ways in which, if you want to dig into Southern food, you're explicitly digging into issues of race, class, gender, ethnicity."

Edge is the director of the Southern Foodways Alliance, part of the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. And he says those two things — Southern food and culture — are inextricably intertwined. As he writes, "agriculture begat the region's original sin: slavery."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

But food is also a lens to trace where the South is now, as an influx of immigrants has transformed the region, and as Southern cuisine itself has gone from being thought "retrograde" to being recognized as "foundational to American cuisine."

His book spans a 60-year period, telling the story of the South, decade by decade, through food — from the kitchen of Georgia Gilmore, who organized cooks and bakers to sell food to raise funds to support the Montgomery, Ala., bus boycott, to the modern Southern artisanal food movement.

One of the fascinating stories it shares is that of Fannie Lou Hamer, the famed voting rights activist from Mississippi who also became what could be called a "food sovereignty" activist. In the late 1960s, she began amassing farmland and organized a livestock sharing program — which she called the Pig Bank — that recruited poor, rural black families in her native Mississippi Delta to care for pregnant female pigs. The families returned two piglets to the bank, which were then shared with other families. By the second year of the program, 100 families had pigs to slaughter.

"What she was attempting in the late 1960s seems modern even today," Edge says.

Edge spoke recently with NPR. A transcript of the conversation follows, edited for brevity and clarity.

Southern food can go from grits to greens to tamales. What is Southern food? Southern food is for me a story of people as much as ingredients or dishes. Tamales, a food that's very popular just west of where I live, in the Mississippi Delta, shows the early imprint of Mexican migration into the Mississippi Delta to work cotton harvests in the early 20th century. Each dish spins a narrative of the region I call home. A lot of these dishes which give us pleasure were created by people in subjugation, sometimes created for their overlords.

Indeed, the title of my book references just that sort of dish. You took a pot of greens — could be collards and mustards — and cook it down, low and slow, with pork hocks or pig tails. And the liquid that remains at the bottom of that pot, the distilled essence, is the "potlikker." And there's a subversive beauty in that dish. During the days of enslavement, slave masters would often retain the greens for themselves and deign to give the potlikker to the enslaved, not knowing that the nutrients leach out of those greens and remain in the potlikker. So the slaves were left with what was truly the nutritious part of the dish.

For me, this book was an attempt to boil down, distill down 60 years of Southern history and offer voice to all those cooks who express themselves through a kind of subversive creativity in the kitchen and the fields and at tables.

Does the fact that you're a white man writing about Southern food skew your work in certain directions? I grew up in the home of a Confederate brigadier general in small-town Georgia, with a historical marker out front that celebrated exploits of Gen. Alfred Iverson Jr. If you read that marker you'd think him a hero. If you dig into your history like I've done, you'd recognize he was not. So much of the history of American South is mythos and fable. As a white son of the South, I feel it my duty to tell a truer, more honest history of my place, to look our past squarely in the face. There are now Southern restaurants in Brooklyn. I mean Southern food is hipster food. What does that say?

It says a lot. Southern food has been cyclically hip for the last 50 years. In the late 1960s, America fell in love with soul food, which is the food of rural, black Southerners who moved north. By the 1970s, the American press falls in love with Jimmy Carter, the peanut farmer, falls in love with grits and the references to grits as "Georgia ice cream." By the 1980s Paul Prudhomme steps to the stage. And Paul Prudhomme, son of Opelousas, La., the proselytizer of Cajun cuisine, Louisiana cuisine — the 1980s are his.

I think it also reflects a kind of mainstreaming of the American South. For the longest time, we were an exotic place and we were exotic people, outside the American mainstream. And this latest love affair with the region reflects a not-quite-redeemed South, but a fitfully redeemed South — a South kind of reclaiming its history, staring it down, and now reinterpreting it.

And does it change the food? Is that OK? It changes the food. What I hope it doesn't change is the narrative. That's really what's important to me ... if we're going to canonize fried chicken in the roster of great American dishes, we also canonize George Gilmore, a great fried chicken cook from Montgomery, Ala., who leveraged the talents of the stove to drive change in our region. What about changing demographics in the South? More people are arriving from Central America and Asia, for example. The South, over the span of 60 years, has changed more briskly than any other region of our nation. You see that in my son, who's now 16. I grew up going to eat barbecue sandwiches on a Saturday afternoon. He's more likely to opt for tacos al pastor and salsa verde. In a city like Houston, you see Vietnamese Cajun crawfish restaurants spread across the city. I see all these beautiful combinations coming into focus. A new, kind of "future-tense South" is at hand, and it is in the hands of immigrants — Southerners, first-generation Southerners. Is it a good and gratifying time to be writing about Southern food? We now as a nation recognize, in ways we never have before, the value of our food culture. We recognize food as an expression of people and place, comparable to the way we express ourselves through literature or music or religious expression. Michael Twitty's book, The Cooking Gene, will soon be out in August. [Twitty is a chef and historian who explores African-American foodways.] Ronni Lundy just published her beautiful book, Victuals, about Appalachian food culture of the American South. There are a range of conversations going now, at a moment when we recognize the value in our meals is more than about sustenance. There's deep meaning in there. Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

(2017-06-13 04:00:00 UTC):

An earlier version of this story incorrectly referred to the book Victuals by Ronni Lundy as Vittles.