Is Cleveland a model for med-tech success in Rochester?

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Hungry to launch his medical technology firm, Jake Orville first needed a city with the research brainpower he'd require and the workers and workspace he could afford.

Cleveland was not the sexy answer a decade ago, but it turned out to be the right one.

At Cleveland Clinic, the city's world-class health and medical facility, Orville found the diagnostic technology he wanted to commercialize and sell. In 2009, it grew into Cleveland HeartLab, a 200-person company developing biomarkers to help doctors predict cardiovascular risk.

"I was just blown away at the ecosystem that was here to take people like me, start companies like Cleveland HeartLab, attract investors, get incubation space and then go," Orville said of the city.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Cleveland Clinic is the gravitational force in a medical-technology universe that's now pulling businesses, investor money and millennials into the city. It's a success story that Mayo Clinic and Rochester leaders aim to write in Minnesota.

While the cities are obviously very different demographically and economically, Rochester and Mayo officials see parallels between Cleveland's success and Rochester's ambitions as they try to attract 30,000 workers to southeastern Minnesota and fulfill a vision for a Destination Medical Center.

It will not be easy. Cleveland became a med-tech destination thanks to important attributes that cannot be found right now in Rochester, including generous state funding, a robust support system for entrepreneurs and a core of like-minded businesses.

A visit to Cleveland offers a look at how that city has improved its economy by cultivating medical innovation, lessons that may chart a path for Rochester and Mayo.

Government subsidies and grub

Cleveland Clinic is wedged between two other idea factories: Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland State University.

With that deep bench of R&D and medical talent, there's been strong support for cultivating the city's med-tech economy, said Pete O'Neill, executive director of Cleveland Clinic Innovations, the clinic office that turns ideas born within the clinic's walls into marketable products.

"You can't build an ecosystem with just the Cleveland Clinic," he said. "We've seen the region really embrace that health care commercialization can be a driver for economic development."

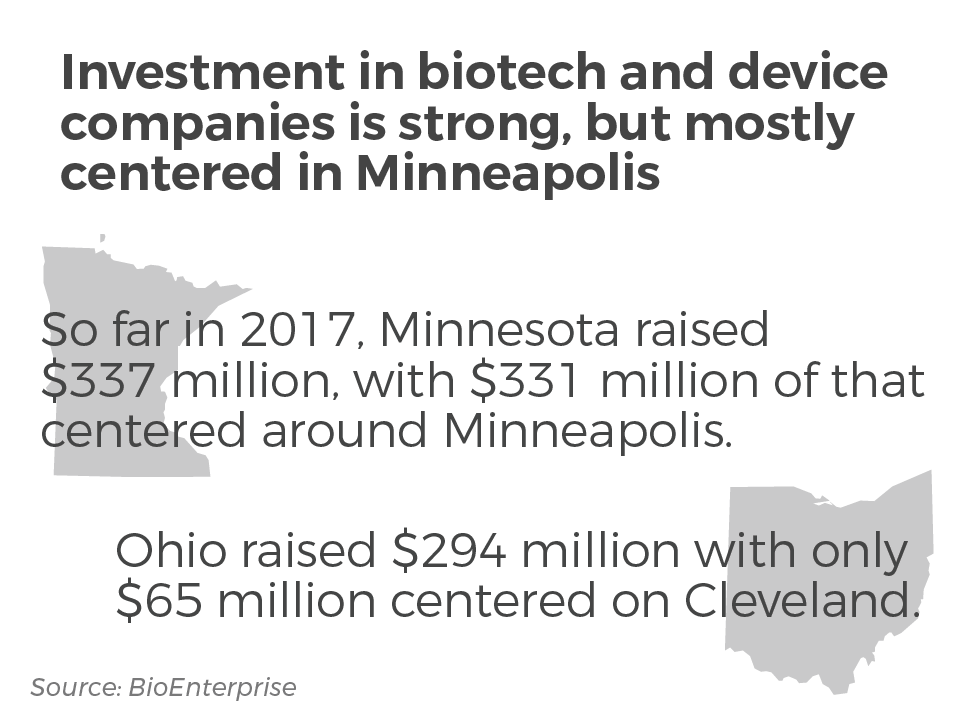

The growth is fueled with massive state subsidies. In 2002, Ohio committed $2.1 billion to grow and keep new tech companies in the state. More than $250 million has gone to Cleveland organizations over the past decade. The region boasts more than 700 biomedical companies.

The city's innovation economy is reaching critical mass. Big names like IBM and Medtronic are buying up local companies — in some cases for more than $1 billion — and keeping those companies in Cleveland.

Just last month, Orville's Cleveland HeartLab recently agreed to sell itself to Quest Diagnostics, a Fortune 500 medical testing company.

"Now you have companies that are big enough, have relationships in Cleveland that are important enough that the acquiring entity wants to use that as a foothold in the Cleveland market to grow," said Aram Nerpouni, CEO of BioEnterprise, a local business incubator.

Bus line drives billions

A ton of money has gone into downtown, which had been a dead zone.

State and federal tax policy helped Cleveland convert elegant historic buildings downtown to residential spaces over the past decade, and demand has been strong, said Michael Deemer with the Downtown Cleveland Alliance.

Now, it's a destination for millennials, who make up nearly two-thirds of the residents. New restaurants, a pedestrian area, and dozens of retailers have followed.

"Authenticity and taking advantage of your legacy and your history is part of what the millennial generation is looking for," Deemer said on a day when food trucks lined up to sell crowds of young professionals everything from Greek food to smoothies and the city celebrated a milestone — 15,000 downtown residents.

Cleveland also went big on public transportation, spending $200 million on the HealthLine, a rapid transit bus system along Euclid Avenue, which forms the spine of Cleveland's Health Tech corridor and connects downtown with Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland Clinic.

"I use it every day," said Kimberly Ho-A-Lim, who's in her twenties, lives downtown and uses the HealthLine to get to school at Case Western and work at the clinic.

"It passes pretty frequently, so it's quite convenient," she said as her bus headed east toward the clinic.

Euclid Avenue, once the city's rundown main drag, is now attracting new businesses. The city says in a decade, the HealthLine has attracted $6 billion in real estate investment.

Cleveland hasn't solved every problem. Despite the downtown success, the housing stock around Cleveland Clinic is in bad shape and poverty is high.

The clinic is trying to work closer with its neighbors to solve the housing woes. It recently gave a community development group $500,000 to assist the development of affordable housing near the clinic's campus. The clinic and other employers also provide financial incentives for staffers to move nearby.

Cleveland Clinic's relatively recent interest in the local housing stock is welcome news. The Clinic's involvement will help bring new life, business and younger workers to the neighborhood, said Denise Van Leer, executive director with the community development group Fairfax Renaissance.

"The residents and interns that come, they want to be within walking distance. So it's in their best interest, too," she said.

'Need a critical mass'

Rochester and Cleveland share some of the same DNA. Cleveland Clinic, Mayo Clinic's rival, adopted the Mayo brothers' approach to medical care.

Now, Rochester views Cleveland as one of the models to emulate as it tries to grow its fledgling entrepreneurial community.

Entrepreneur Drew Flaada's experience finding investors in Rochester is much different that Jake Orville's as he cultivated Cleveland HeartLab a decade ago.

"It was tough to find local capital, to tell you the truth," said Flaada, chief technology officer for Ambient Clinical Analytics, an early-stage Mayo Clinic-grown software company that has successfully attracted investor interest, but mostly from outside the region. Twin Cities early stage investor Pam York agrees support for tech start-ups could be better throughout Minnesota. "Given the number of accredited investors here the number of smart people, you'd think it would grow faster."

York said she and other investors are eagerly watching Rochester's development. She points to the construction of a tech campus downtown as an important step.

While that new campus will play a vital role in building a med-tech future, Rochester leaders also acknowledge they must find answers to the city's downtown housing needs.

Lisa Clarke, head of the Destination Medical Center, says Rochester wants to be a place where millennials can live, work and enjoy their weekends without driving.

"They want this urban environment," she said. "They want density. We are building that."

Clarke also believes Rochester has an advantage in that it's long been prosperous and, unlike other cities, doesn't need to first clean up decades of decay.

Housing advocates, though, say Rochester is way behind in meeting the city's current needs, let alone the future.

Mayo Clinic housekeeper Mary Bale says there may be a host of new condos downtown, but few are affordable to employees like her. "They need more affordable housing so people can work here and live. It's not like we're millionaires."

At this point, the clinic isn't putting money toward a fix, although Mayo and DMC officials say they are working to address the issue.

Rochester City Council member Nick Campion says Mayo can't grow without workers. And workers at all income levels need housing.

"There's really no better time for our large employers to take stock of how much is at stake for them," he said.

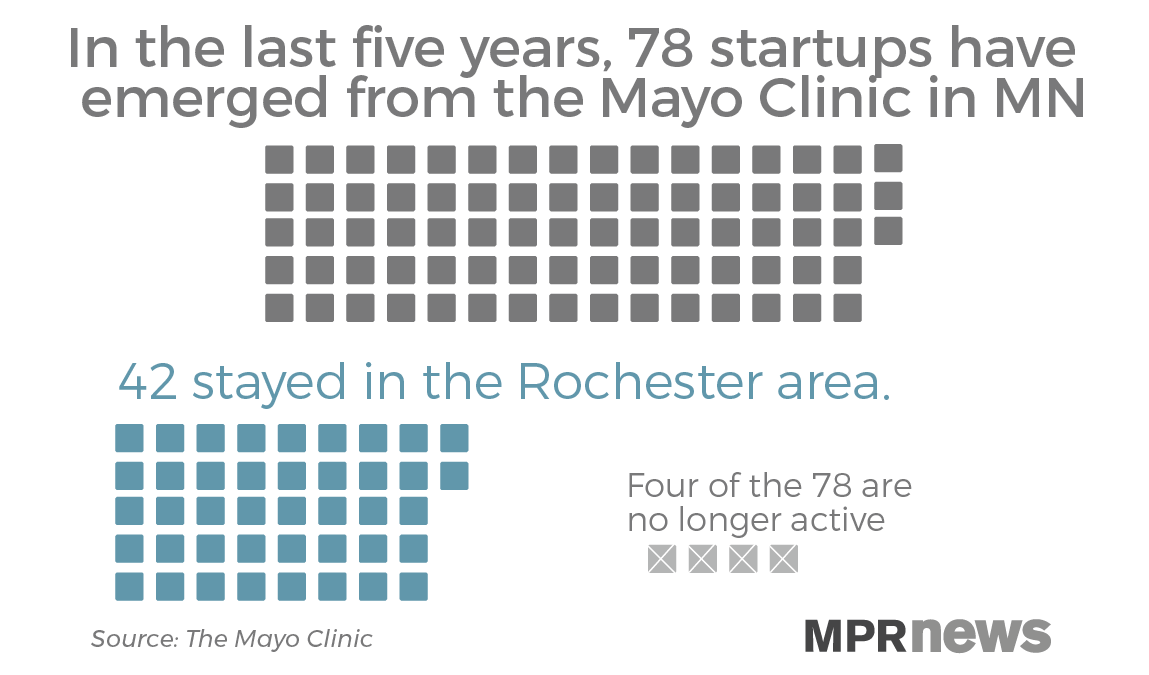

And Rochester is making progress now, said Jim Rogers, Mayo Clinic's business development chief. He points to a downtown business accelerator Mayo launched with the city, and a new $1 million local investment fund; investment in startups this year is already more than double last year's total.

"I've always felt that you need a critical mass," said Rogers. "We're starting to see that here."

Editor's Note: (Nov. 9, 2017): A graphic in an earlier version of the story indicated that 78 startups emerged from the Rochester area in the last 5 years. To clarify, 78 startups emerged directly from Mayo Clinic in Minnesota. (Nov. 10, 2017) Due to an editing error, the original audio version of this story overstated the size difference between Cleveland and Rochester. The Cleveland metro area has about 10 times more residents than Rochester's.

Correction: (Nov. 10, 2017) A previous version of this story misstated the location of the Cleveland Clinic. The story has been updated.