Investigation: For some who lived in it, Keillor's world wasn't funny

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: 5:25 p.m. | Posted: 3:39 p.m.

When Minnesota Public Radio abruptly severed ties with Garrison Keillor in November, the sole explanation offered by the company was "inappropriate behavior" with a female colleague.

For his part, the creator and longtime host of A Prairie Home Companion described his offense as nothing more than having placed his hand on a woman's back to console her.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

An investigation by MPR News, however, has learned of a years-long pattern of behavior that left several women who worked for Keillor feeling mistreated, sexualized or belittled. None of those incidents figure in the "inappropriate behavior" cited by MPR when it severed business ties.

Nor do they have anything to do with Keillor's story about putting a hand on a woman's back:

• In 2009, a subordinate who was romantically involved with Keillor received a check for $16,000 from his production company and was asked to sign a confidentiality agreement which, among other things, barred her from ever divulging personal or confidential details about him or his companies. She declined to sign the agreement, and never cashed the check.

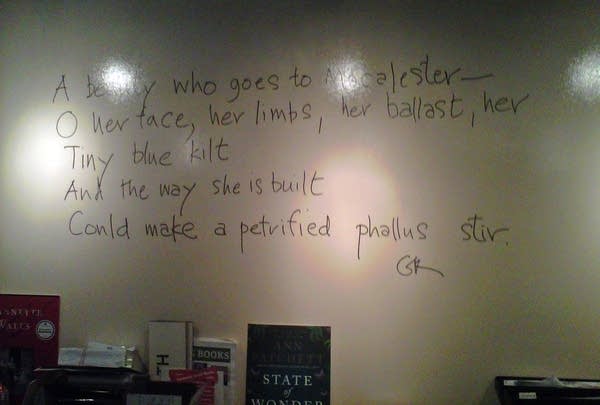

• In 2012, Keillor wrote and publicly posted in his bookstore an off-color limerick about a young woman who worked there and the effect she had on his state of arousal.

• A producer fired from The Writer's Almanac in 1998 sued MPR, alleging age and sex discrimination, saying Keillor habitually bullied and humiliated her and ultimately replaced her with a younger woman.

• A 21-year-old college student received an email in 2001 in which Keillor, then her writing instructor at the University of Minnesota, revealed his "intense attraction" to her.

MPR News has interviewed more than 60 people who worked with or crossed professional paths with Keillor. Most spoke on the condition of anonymity because they still work in the industry or feared repercussions from Keillor or his attorneys.

The revelations create a portrait of Keillor more complicated than that of the folksy, avuncular storyteller whose brand of humor appealed to millions of listeners. They suggest a star who seemed heedless of the power imbalance that gave him an advantage in his relationships with younger women. They also raise questions about whether the company knew enough — or should have known enough — to stop the behavior of the personality who drove much of its success.

In an email to MPR News on Monday, Keillor said he could not comment for this story in part because he was in negotiations with Minnesota Public Radio over their business relationships. "But beyond that," he wrote, "I don't think MPR News can report fairly on MPR management's chaotic and disastrous actions."

He went on: "I think it would be a waste of time to engage in the he said/they said game. There are facts here that need to be respected. I'll be able to tell my side of the story at length, in my own words, in due course, and that's sufficient for me."

For weeks, Minnesota Public Radio refused MPR News' repeated requests to comment on the company's separation from Keillor. But as negotiations with Keillor's company stalled and pressure from news organizations mounted, Jon McTaggart, president and CEO of MPR and American Public Media Group, broke his silence.

In an interview with MPR News Tuesday afternoon, he said the company's separation of business interests from Keillor came after it received allegations of "dozens" of sexually inappropriate incidents involving Keillor and a woman who worked for him on A Prairie Home Companion. He said the allegations included requests for sexual contact and descriptions of unwanted sexual touching.

McTaggart, who after the interview with MPR News sent an email to MPR listeners and members further explaining the separation from Keillor, says cutting Keillor off was the most painful decision he's made as CEO. But in-house and external investigations into the matter bore details he could not ignore.

"When we reached a point that from all sources we had sufficient confidence in facts that really required us to act, we took the action we did," he said. "It was the right thing to do. It was the necessary thing to do, and we stand by it."

'She recoiled. I apologized.'

Although Keillor and MPR were instrumental to each other's success, Keillor hasn't been an MPR employee since 2002. That's when MPR entered into a contract with Keillor's company, Prairie Grand, to produce his shows. An MPR spokesperson said that until the recent separation, "MPR had financial and legal obligations to Prairie Grand related to licensing and production."

Keillor's abrupt departure from MPR's airwaves, announced by McTaggart about eight weeks ago, came as a shock to his legions of fans and listeners. Reactions ranged from dismay to outrage and perplexity.

When he made the announcement, McTaggart declined to offer details of the inappropriate behavior Keillor had supposedly engaged in, and reportedly told employees at an off-the-record meeting in December that he alone, among staff of American Public Media Group, MPR's parent company, knew the content of the allegations against Keillor.

McTaggart said specifics had been shared only with lawyers — "MPR retained an outside law firm to conduct an independent investigation of the allegations," the company said in its Nov. 29 statement — and a committee of APMG Board members. The company added that "there are no similar allegations involving other staff," and McTaggart said Tuesday the external investigation is "substantially complete."

On the day the news broke, Nov. 29, 2017, Keillor told the Star Tribune that he had placed a consoling hand on a colleague's bare back. "I meant to pat her back after she told me about her unhappiness and her shirt was open and my hand went up it about six inches. She recoiled. I apologized," Keillor wrote.

In emails to MPR News, Keillor also claimed that Minnesota Public Radio's decision to sever ties with his companies resulted from an extortion scheme by an ex-employee. He suggested that the person had been fired and rebuffed in his demand for a generous severance payment, then solicited a former Prairie Home colleague to allege inappropriate behavior.

"This is an extortion scheme and McTaggart gave in to it," Keillor wrote. "It's just about that simple."

McTaggart said Tuesday he rejects that idea. "I certainly don't accept the premise of extortion or blackmail," he said. "That has nothing to do with this."

What it has everything to do with, McTaggart said, is power.

"We hold our leaders and people in power to a really high standard," he said. "Leaders and people in power determine livelihood. We determine your career, whether you have a job or don't have a job, what your compensation is going to be. And there's a pretty clear set of policies that have guided our decision-making about what's appropriate."

The revelations add context to an MPR News investigation into Keillor and his pattern of troubling incidents and workplace relationships.

In scores of interviews with former staff members of The Writer's Almanac, Prairie Home and at Keillor's St. Paul bookstore, MPR News reporters were unable to verify the story of Keillor putting his hand on a woman's back, or his claim of extortion. But there are many who describe other troubling incidents or relationships.

MPR News has learned in its reporting that over roughly the past decade, Keillor had at least two romantic relationships with women in workplaces that he led, according to three people with direct knowledge of the encounters and four former colleagues who said Keillor's affairs were open secrets in the office.

Those relationships were consensual, colleagues say, but not without harm due to the power dynamic.

One of those women in 2009 was offered a $16,000 check from Keillor's Prairie Home Productions, along with a proposed confidentiality agreement and a new work contract. The woman never cashed the check, and she didn't sign the non-disclosure agreement or the contract.

A friend in whom the woman confided at the time of the affair told MPR News that Keillor seemed to punish and reward her at work based on how they were getting along in private. The friend said the woman suffered financial and professional consequences from her relationship with Keillor.

"The minutiae of whether he had affairs — that's none of my business," said the friend, who asked that her name be withheld because publishing it could expose the subordinate's identity.

"The business that is mine is how it affected these women in their careers. With my friend, it took out a big chunk of her drive. The thing that's horrible is the impediment it became to her as she was trying to do her job and make a living."

Many individuals, including female collaborators spanning a range of ages, said they admired and respected Keillor.

They also were baffled by the notion that Keillor, whose social awkwardness is legendary, could have crossed professional bounds with women.

Francesca Caviglia, who worked as an assistant for Prairie Home Productions after graduating from St. Olaf College, remembers interviewing for the job at Keillor's St. Paul home, where Keillor's wife and daughter also welcomed her. Caviglia said Keillor answered the door in a dress shirt, pair of slacks and red socks.

"My initial impression was that his persona matched the character I had heard on the radio," said Caviglia, who grew up in New England listening to Prairie Home in her kitchen with her parents. "He's sort of a little aloof and detached. He doesn't make a lot of eye contact or exchange small talk."

When Keillor was in the office, she remembers him roaming the halls, singing under his breath and stopping in the doorways of his staff to drop his next big idea.

"I always thought maybe he was writing in his head," Caviglia said. "There are times when he can come off as rude or brisk. He says what he needs to say, asks what he needs to ask you, and then moves on his way."

But she's unsettled by the notion that Keillor may have acted in a way that would have justified what she considers MPR's quick dismissal of him.

"It's confusing to me that there's anything that happened that would warrant that type of response. I never got that impression from him or anyone else on the staff," Caviglia said. "It was an odd time in my life, it was my first job out of school, and I have mixed memories about the stress of that time. But overall, the people — and Garrison included — I only have positive memories of."

When Amanda Stanton handled marketing for Prairie Home Productions from 2003 to 2006, she said, Keillor was usually holed up in the office, lost in thought with a notepad or book in hand. And despite his shyness, the boss she knew showed concern for all his staff.

"He was wonderful in the sense that he treated men and women very much the same," Stanton said. "There was so much respect in the way he worked with his male and female producers."

When Stanton wanted to return to work from maternity leave after giving birth to twins, Keillor insisted she bring the babies and their nanny with her to the office. He allowed her to set up a room next to his office, replete with a baby gate at the door, where the infants could play and be close to their mother over the next several months.

Stanton describes the work culture as a "respectful family atmosphere." She can't reconcile the allegations of inappropriate behavior with the man she calls the "most reserved boss I have ever worked for."

On the show, Keillor often sang duets with younger female musicians, including Andra Suchy. On the day MPR's split with Keillor was announced, she shared her impressions of Keillor on her Facebook page:

"Please don't ask me anything about that. You know what I mean," she wrote. "I know him to be a genius with a kind and tender heart who genuinely cares for a great many people (his family first and foremost)...and very, very funny."

Sue Scott, a core member of the cast of actors who worked on Prairie Home, said MPR needs to be more forthcoming about its reasons for cutting Keillor off. She questions how McTaggart could have arrived at that decision before the company's investigation had even concluded.

And because he was implicated on the same day as Matt Lauer, who was fired by NBC after accusations of severe sexual misconduct, the question of what Keillor did was left to the worst of the public's imagination, said Scott, who worked on the show for 24 years. She says people are wrongly conflating "inappropriate behavior" with "sexual predator."

"Everybody needs their day in court, and Garrison needs his day in court," said Scott, who added she has pressed MPR leadership for more answers. "Of course, people are thinking of the worst. That's why we need perspective here."

A lawsuit

No one who spoke to MPR News, not even those who found Keillor's behavior to be improper over the years, likened it to that of Lauer or Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein.

But concerns about Keillor's interactions with women and claims that he had abused his power surfaced nearly two decades ago. These early allegations stemmed not from unwelcome advances, but from accusations that he treated women unfairly.

In 1999, a woman fired from Minnesota Public Radio after three years working on The Writer's Almanac sued MPR in federal court, claiming age, sex and retaliation discrimination.

Patricia McFadden, then 41, alleged that MPR terminated her at Keillor's request, falsely stated that her firing was due to "restructuring," and replaced her with a younger woman.

In her lawsuit, McFadden claimed she and other women who worked on the show were subject to a "pattern and practice of abusive conduct" by Keillor that included "hostile and demeaning" emails and memos. McFadden also claimed that she performed the work of a producer, but her position was titled "coordinator," and she was paid only for a coordinator's work. She said male employees at MPR were "not subjected to such disparities in pay and position title."

In a recent interview with MPR News at her St. Paul home, McFadden, 60, said her job involved researching literary history to find notable events about writers to feature on the daily program, writing radio scripts for Keillor and finding new poetry.

She found the task interesting and rewarding, but said Keillor seemed to take delight in disparaging her work, often crumpling up scripts in a dramatic fashion to humiliate her.

"He would complain that there were too many women," McFadden said. "He didn't want too many female poets or authors to be highlighted. He wanted to know if I was using some kind of 'women's calendar' because there seemed to be too many women in this week's Writer's Almanac."

McFadden said she was not the victim of any overt sexual harassment by Keillor, but she and her female colleagues bore the brunt of his bullying and suffered the most from his mercurial management style.

Keillor often refused to inform McFadden and her female co-workers of his schedule and would show up hours late for his weekly recording sessions, she said, making an intense production schedule even more challenging. In these instances, McFadden said, Keillor would typically apologize to the men on the crew while ignoring the women.

Eventually, she'd had enough, and complained to MPR management. In 1998, after McFadden had worked at The Writer's Almanac for nearly three years, her supervisor abruptly informed her that her job was being eliminated because of restructuring. But McFadden said in her lawsuit that MPR actually replaced her with a younger woman. MPR denied the allegation in court filings.

Angered by her treatment and without recourse inside the company, McFadden sued MPR in federal court. McFadden's attorney said the case was resolved before trial in 1999, but did not go into further detail. Typically, such cases are settled out of court. For her part, McFadden said that suing MPR was never about the money.

"I really didn't want a settlement of any financial sum," McFadden said. "All I wanted was to continue working as a producer at MPR. All I was looking for was a position in another area as a producer, and that they were unwilling to do."

But since the revelation last October of sexual assault allegations against film producer Weinstein and the #metoo movement it reignited, McFadden said, it's important for men in positions of power to be held accountable for their actions.

"I think people who have power and influence and good fortune have more responsibility to behave well than anybody," she said. "And it should not be an excuse to behave badly and to treat others so poorly, especially women."

A judge sealed the documents related to McFadden's case soon after she filed it. Her allegations about Keillor remained hidden from public view until 2010, when then-Chief U.S. District Judge Michael Davis ordered them unsealed as part of a routine review of old cases.

'A catch-22'

When Liz Fleischman was in her mid-20s, she, too, worked as a producer for The Writer's Almanac. She tells an almost identical account of how Keillor "kind of violently" crumpled up papers and slammed them into the garbage can to show his dissatisfaction with her work.

"I didn't take it that personally," she recalled. "But I remember telling my roommates what had happened, and they said, 'He did what? You shouldn't be treated like that.'"

As he did with other staffers over the years, Keillor eventually started giving Fleischman the silent treatment, she said. One day she learned she would lose her job to someone even younger.

Fleischman had the option of finding another position with Prairie Home but decided it was time to move on.

She agrees with the crux of McFadden's lawsuit: Keillor treated the women writers and producers who worked for him poorly.

Fleischman also describes a paradox: Keillor made it a point to hire young, inexperienced staffers, perhaps out of a desire to give fresh talent a chance, but underestimated what the jobs required. Then he lost patience and cast them aside when he discovered their incompetence, she said.

"So it was a catch-22," she said. "He would hire young people, he would get disappointed, he would freeze them out, and he would start all over again."

Still, her feelings about her old boss are complex. Many years later, after Fleischman moved to New York, she was at her job with Morgan Stanley in the World Trade Center when terrorists attacked in 2001. The towers fell, some of her colleagues were killed, and she escaped.

Keillor later reached out to Fleischman in what struck her as a sincere email.

"When I got the letter, it kind of changed how I thought about him. ... I appreciated his kindness," she said. "Like a lot of men of that generation, he has a lot of sexist patterns that keep him from working well with women. He has a communication problem where he doesn't communicate with people face to face."

"I felt bad that he has that," she said. "But in his heart, I think, he is a kind person."

How much did MPR know?

Jon McTaggart, who first joined the company in 1983, said that when he made the decision to sever ties with Keillor, he knew of no other allegations against him.

But McTaggart's predecessor, MPR founding president Bill Kling, did know of other allegations. Both Kling's and Keillor's alleged behavior was cited in McFadden's lawsuit against MPR. Kling declined MPR News' request for comment on this story.

Fleischman, the former producer, said just as she was leaving MPR, she wrote Kling alerting him to Keillor's treatment of his employees. At first, she said, he expressed his interest in meeting with her to hear more. But Fleischman said he never followed up.

She learned the details of McFadden's 1999 lawsuit only recently, when a reporter read portions of the publicly available complaint to her. She backed up many of McFadden's claims.

"Over the years, I've wondered, 'Was I too wimpy? Was I not good at my job? Was I too sensitive?'" Fleischman said. "I've always gone back and forth as to whether I was in the right or wrong to send that message to Kling."

Looking back, though, she said Kling should have taken the time to listen to her thoughts about Keillor.

"He really should have, because he could have prevented what happened going forward," Fleischman said. "It didn't have to be that way. A talent could change their behavior and continue to be a talent and continue to do well. You don't have to be one or the other, you could be both. You could be a kind manager and a very talented manager at the same time."

Aggressive silences

People who worked with him across the decades say Keillor could be funny, charming, compassionate and gracious.

By other accounts, he could be cruel and dismissive. The office was driven by his moods, former colleagues say. A common complaint is he would punish his staff with prolonged aggressive silence, as Fleischman described.

He also grew tired of and discarded musicians, writers and staff, many of whom had been loyal to Keillor for years. Some employees were terminated without warning.

The relationship between MPR and Prairie Home is confusing even to people who work at both organizations.There's physical distance: Members of Keillor's staff worked away from MPR headquarters. Prairie Home Productions is nestled in a squat commercial building, which workers called "The Fort" and was long used as a radio station in a residential neighborhood of St. Paul.

There's an organizational distance, too: Several people associated with Keillor's shows said that even though they received paychecks, benefits and other services from MPR, they were unclear on where to report workplace concerns about Keillor or the environment he cultivated.

"We were all in this weird bubble of protecting him and keeping him happy," said one former employee who worked on Keillor's shows. "He clearly impacted the dynamics of everyone around him."

Several staffers engaged in backbiting and finger-pointing in order to preserve their jobs. Some described the office as gossipy, bordering on hostile. Others noted Keillor's penchant for hiring his family members, former nannies and others in his personal life, leaving them to wonder if their own jobs were safe.

But was he sexist? Some former colleagues say he was as dismissive with men as he was with women. A typical grievance was that Keillor was the sole arbiter of what worked or what didn't work for the shows. He had problems articulating why staffers were not hitting the mark.

"It was sometimes exhilarating, sometimes frustrating, sometimes terrifying," said a former staff member, speaking generally about his time working for Prairie Home. "I'm glad I had the experience, but it's not something I would want to repeat."

'So wildly inappropriate'

The latest allegations about Garrison Keillor's treatment of women run contrary to the clean-cut, wholesome reputation of A Prairie Home Companion.

Yet there has always been a dark side to some of Keillor's characters. One person who worked on the show said you only have to look at the popular segments such as "Guy Noir" and "Lives of the Cowboys" to see recurring portrayals of women as saloon floozies or femmes fatales, side characters in cowboy and hard-boiled detective dramas.

They are throwbacks to another time, but they have delighted audiences for years. It all seemed in good fun, but for some of the women who worked in Keillor's world, the reality was no laughing matter.

Two former employees of Common Good Books, the St. Paul bookstore Keillor owns, learned that one awkward day in May 2012.

Molly Hilgenberg, now 31, said Keillor visited the shop only occasionally and left its day-to-day operation to employees. But he did stop by shortly after the bookstore moved from a basement in the Cathedral Hill neighborhood to a larger building near Macalester College.

Hilgenberg, who now lives in northern California, said Keillor wrote a sexually suggestive limerick on a whiteboard behind the cash register. In the five lines, photos of which Hilgenberg shared with MPR News, Keillor wrote about another young female employee, whose physique he found arousing. Hilgenberg said she is certain that her co-worker was the subject of the poem.

A beauty who goes to Macalester —

O, her face, her limbs, her ballast, her

Tiny blue kilt

And the way she is built

Could make a petrified phallus stir.

Hilgenberg's co-worker was a Macalester student at the time. She did not want to be named, but confirmed the details of the incident to MPR News.

Hilgenberg said they both found the verse offensive and demeaning, but felt powerless to do anything about it.

"I'm pretty sure I didn't say anything other than 'Oh my gosh!'" Hilgenberg said. "I don't even really remember my reaction. I was just in shock. I was like, 'That is so wildly inappropriate' in my mind. But I didn't say anything, which I still regret to this day."

Hilgenberg said the store staff feared Keillor's reaction if they were to erase the limerick, so they temporarily covered it with books and a portrait of F. Scott Fitzgerald.

But after consulting with their manager, who Hilgenberg said was "a great boss," she and a second coworker erased the verse. Their concern about Keillor's reaction was prescient, Hilgenberg said. He became angry upon seeing the blank whiteboard at his store.

Keillor would eventually apologize in a handwritten note to the employee who was the subject of the limerick. She no longer works at the store, and said she did not hang onto Keillor's letter. But nearly six years later she recalls that it rang hollow, and that she thought it was patronizing and demeaning.

"The opening line, I do remember, was, 'I'm sorry my limerick made you feel bad,'" she said. "It actually wasn't an apology at all. Then he went on to explain what limericks were."

Neither Hilgenberg nor her coworker quit over the incident; each says she never experienced or saw any other inappropriate behavior in their remaining time at the store.

Several years later, Keillor would describe on Facebook a fictional episode with a similar theme. On Dec. 19, 2017, weeks after the MPR breakup, he posted that he was making progress on a screenplay about Lake Wobegon.

"I have finally decided not to kill off the dad," he wrote. "Instead of coming home for his dad's funeral, John now comes home because he's been fired for a limerick with sexual innuendo in it and sending it to a number of fellow employees including one who considered it an assaultive act."

The bookstore poem may not have been an assaultive act, but it's not harmless fun, said Steven Andrew Smith, an employment attorney who represents plaintiffs in sexual harassment cases.

"A limerick about an erection is probably not a limerick you want to be telling in the workplace," said Smith, who is not involved in any cases related to Keillor. "I can't imagine how humiliated this person must have felt when they saw this up publicly at work."

An 'intense attraction'

In early 2001 Keillor returned to his alma mater, the University of Minnesota, to teach a comedy-writing class. Student Lora Den Otter eagerly enrolled. At the time, Den Otter, then known as Lora Barstad, had aspired to be a professional writer.

She remembers leaping at the opportunity to learn from a man whose monologues she first heard while growing up in Sioux Falls, S.D. Her grandmother's cassette tapes of "News from Lake Wobegon" were part of the soundtrack to Den Otter's childhood.

For one writing assignment, Keillor asked his students to write a letter that started as a minor complaint but grew increasingly hostile. Den Otter directed her letter to the makers of "Days of Our Lives" to lament the imbecility of the soap opera's latest plot lines.

That exercise caught Keillor's eye. With her permission, he wove it into a ketchup commercial on "Prairie Home," and the show paid her $50, recalled Den Otter, who was then 21. And she was ecstatic.

"I loved writing and I wanted to do it for a career, and so I felt like, 'Oh my gosh, this is my shot — someone has taken notice of me,'" Den Otter said.

But everything changed after she emailed Keillor about the possibility of an internship, which was required for her journalism major. Keillor emailed her back, saying she could intern for the show. He also provided Den Otter with a contact.

According to Den Otter, he then wrote something unexpected, to the effect of: I'll have to suppress my intense attraction to you, but that can be done.

Den Otter recalls brushing off the remark and trying to make light of it in her reply. But the self-assurance she initially felt after Keillor took a shine to her work deflated. She concluded that the only reason Keillor noticed her work was that he was attracted to her.

"Looking back, I can say that I think it was a bigger blow to my confidence than I realized at the time," said Den Otter, who is now 38 and teaches high school English. "It made me sort of more easily give up on wanting to be a writer because that self-doubt became a lot stronger."

She no longer has the email; it was sent to her university address, and the university has switched systems. But her brother distinctly remembers her telling him the story shortly after it happened.

Her mother, Donna Barstad, vouches for Den Otter's story and said she saw the email from Keillor. "I just thought, 'Another celebrity who is attracted to women a whole lot younger than him,'" Barstad recalled.

Den Otter completed the the Prairie Home internship — a position that had her researching towns that Keillor's show visited on tours — that same school year. She worked remotely and never heard him say anything inappropriate again.

Den Otter said she couldn't bring herself to share the incident widely. One factor, she said, was worry about the wrath of people who would choose to believe their trusted bard over her.

"He's so beloved in this state," she said. "A big fear was people coming out with the pitchforks and like, 'How dare you say this thing about him?'"

But this fall, as she observed other women sharing their stories of harassment as part of the #MeToo movement, Den Otter felt compelled to speak. After the news broke of MPR's disentangling with Keillor, she took to Twitter, where many of her followers are her own students. She recounted her experience with Keillor and closed the thread with this tweet:

"So I wanted to share this now because I'm thinking of all the amazing young women I have the privilege of teaching and I hate the idea that a man might say something to them that makes them question their talents and worth."

'Nothing to apologize for'

In posts to his Facebook page, Keillor describes himself as hard at work on a novella entitled "Inappropriate Behavior" and on a memoir that deletes MPR from his life's story.

He has revealed that he and MPR are in mediated negotiations over their business relationship, which MPR has confirmed.

MPR said it does not fully own the rights to continue providing archived content for some past Prairie Home and Writer's Almanac programs; Keillor and his companies own many of the rights to the shows' artistic content. Both features disappeared from MPR's website and airwaves when the company announced it was severing business ties with Keillor in November 2017. The show hosted by Keillor's successor, Chris Thile, was hastily renamed Live from Here.

For his part, Keillor seems confident that he's done nothing to merit his treatment at the hands of his former employer.

"I have worked happily with women for my entire life, have nothing to apologize for," he wrote in an email to MPR News. "I have harmed nobody, except perhaps my wife who is a staunch defender and is livid at Jon McTaggart for expunging me from the airwaves and the Internet."

His emails to MPR News frequently point to his age and to his satisfaction in being able to concentrate on his writing.

"My story is interesting," he wrote, "because it's about a privileged person suffering disaster, a hero whose patron has portrayed him as a predator, but in the greater scheme of things it is minor stuff, and the person can easily solve this problem by selling his house and moving to New York. No problem."

He echoed those themes in a Facebook post earlier this month:

A writer who lives in St. Paul

Was seduced by the siren's call

Then took a nosedive

At seventy-five

And survived, and God help us all.

MPR News editors Eric Ringham and Meg Martin contributed to this report.

Editor's note: It is MPR News' policy to use anonymous sources only when the information that they provide can be gained in no other way; when identities of the speakers are known and confirmed by MPR News; and when their accounts have been verified by other sources. Any such use must be approved by senior newsroom management. | More on how we reported this story