Bloomington mosque bombing suspect left trail of trouble

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Federal agents swept into this tiny central Illinois hamlet on Feb. 19 on an anonymous tip about a hidden stash of bombs, but they didn't rush first to the alleged bomb maker's house. They knocked instead on his neighbor's door.

When Jon O'Neill answered, the agents told him they had reason to believe the explosives were on his property but did not believe he was the bomb maker. They suspected O'Neill's neighbor, Michael Hari, and two accomplices planted them in O'Neill's shed and that Hari tipped off the feds.

O'Neill was not shocked to hear his neighbor had tried to frame him. The summer before, he said, Hari had held a gun to his head and tried to stuff him in a car trunk after O'Neill complained about Hari's dogs getting into the garbage. O'Neill's wife said Hari terrorized the couple and their three young daughters for months after they'd called the police.

"He's threatened us and told us if we didn't drop the charges, then something bad was going to happen and we'll regret it at the end," Hope O'Neill said. "So it always played in our heads: Will he really do something?"

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Prosecutors allege that wasn't Hari's only act of violence last summer.

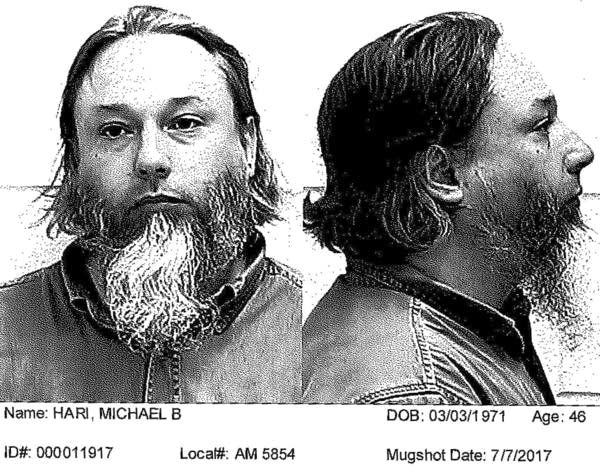

They say Hari, 47, along with 22-year-old Joe Morris and 29-year-old Michael McWhorter, piled into a rented black Nissan pickup, drove eight hours overnight from eastern Illinois to the Twin Cities, smashed a window at Bloomington's Dar Al Farooq Islamic Center and tossed in a pipe bomb.

The Aug. 5 blast heavily damaged the imam's office but none of the five people who'd gathered in the building for early prayers were injured.

Court documents and interviews reveal a past that includes a felony child kidnapping conviction for taking his daughters out of the country, as well as allegations of building bombs and assaulting the O'Neills, his small-town neighbors.

The kidnapping also led him to be featured on TV's "Dr. Phil" show.

Hari was in federal court on Monday. He pleaded not guilty to a firearms charge in a case related to the Dar Al Farooq bombing.

Ski-masked militia man

The O'Neills say they're fortunate it was raining the day the feds came, otherwise their kids, who often play in the shed with neighborhood friends, might have found the bombs before the FBI. O'Neill said agents used a robot to uncover a cache of explosives, including a pipe bomb attached to a small green propane tank, in his backyard shed.

A week later, federal investigators returned to Clarence, Illinois and canvassed the town for information about the explosives. Court documents say a search of a home belonging to Michael McWhorter's brother turned up a cache of guns, including three semi-automatic rifles illegally modified to full auto. McWhorter's family declined to comment.

With the feds closing in, Hari donned a ski mask and set up his video camera. Styling himself as leader of a group he calls the White Rabbit Militia, Hari took to YouTube and asked for help from others who share his disdain for federal law enforcement.

Three other masked men can be seen in the video too. But they don't appear together. With only one balaclava between them, they take turns in front of the camera making similar appeals; each moves out of the frame to hand the mask to the next man.

Hari is well known in rural Ford County and has lived in the area most of his life, said Mark Doran, the local sheriff. "He is an intelligent person. Not much on common sense, apparently," said Doran.

Protests in Waco

Hari spent several years in central Texas when he was in his 20s. In March 1993, just before his second daughter was born, Hari wrote a letter to the editor of the Waco Tribune criticizing the federal response to the siege at the Branch Davidian compound.

In the days to follow, Hari would travel the 90 miles from his home in Lampasas, Texas, to protest at Waco in person.

After getting a bachelor's degree in psychology from what was then the University of Central Texas, Hari returned to Illinois with his wife and two young daughters.

He even worked as a Ford County sheriff's deputy for a few years, though Doran said Hari was forced to resign in 1997 for odd behavior. That included stopping to help a woman whose vehicle broke down, but then handcuffing her and driving her to school.

Hari would soon affiliate himself with the Old German Baptist Brethren, a religious group whose members dress plainly and reject some trappings of modern life.

Hari could often be seen wearing plain clothes and riding around in a horse-drawn buggy, Doran said. But some of his political views seem to be out of sync with the Brethren, who preach non-resistance even in the face of perceived injustice.

"He's what I would call a sovereign citizen," said Doran. "He had a different way of looking at how government was supposed to work, how government was supposed to react to the citizens. Like a lot of sovereign citizens, they want to pick and choose which part of the Constitution they want to follow that day so that it suits their needs, and it's not following what the Constitution is meant to be."

Hari sued the U.S. Department of Agriculture earlier this year, alleging its voluntary produce inspection program unconstitutionally competes with a food safety auditing business he owns. Hari continues to pursue the lawsuit even from behind bars; recently he mailed a handwritten motion from the Kankakee County Jail. MPR News tried to reach him there, but Hari did not respond to a request for comment.

Hari also tried to do business with the federal government. Last year he made a long shot bid to construct President Trump's border wall, claiming he could build it for billions less than a Department of Homeland Security estimate.

The Chicago Tribune wrote a story about Hari's endeavor. A computer rendering in his promotional video shows a grandiose design that looks like a mashup of the Great Wall of China and a Lego castle.

Even as he was alternately suing and wooing federal officials, Hari came to their attention in a way he certainly did not intend.

Two months before federal investigators discovered the explosives in Jon O'Neill's backyard shed, someone sent Doran, the sheriff, pictures of guns and bomb-making materials allegedly belonging to Hari. Doran passed the photos on to the FBI. The anonymous photographer soon became a paid informant for the bureau.

Child abduction, 'Dr. Phil'

This scrutiny from law enforcement and the media is nothing new for Michael Hari. He was in the public eye long before he was charged in connection with bombing Dar Al Farooq.

In 2005, Hari and his ex-wife Michelle Frakes had been in a protracted custody dispute over their two daughters who were by then teenagers. According to court documents, Hari hadn't been taking them to school, so Frakes filed an emergency petition for custody. A day later, Hari took the girls and fled.

The teens were listed with the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. That caught the attention of producers at the "Dr. Phil" show, who offered to help Frakes. The show hired private investigator Harold Copus to track the trio down.

"It turns out that they had left Minnesota, made their way through Mexico, and then entered Belize. And they were in a community in the middle of the jungle way down south in Belize."

When Copus arrived at the Lower Barton Creek Mennonite community, he found immaculate homes and people who abided by a deep religious faith and an agrarian work ethic.

Copus also found Michael Hari, along with his daughters, living in relative squalor. Hari, he said, had been there for the better part of a year, but had done nothing to improve the home he was given. It was dirty, and there were holes in the walls.

"It was a shock to me to contrast between the way I saw the others and how he was living with the girls," Copus said. "It was almost as if he was just living there, expecting someone to take care of him, and that wasn't going to happen. Those are hard-working people. He was not a hard worker; he wasn't pulling his weight."

Copus convinced Hari to return to Illinois, where prosecutors had filed child abduction charges.

Television viewers learned of Hari's odyssey in a series broadcast over three days on the "Dr. Phil Show" in May 2006. The following October, jurors convicted Hari of child abduction, but he avoided jail. A judge sentenced him to two-and-half years of probation.

The road to Dar al Farooq

Hari and his alleged accomplices in the Minnesota mosque bombing are being held now in federal custody without bond in Illinois.

O'Neill, Hari's neighbor and the one who faced Hari's terror a month before the Dar Al Farooq bombing, can't answer those questions. But he's seen Hari's anger well up into violence for something as a minor as a dispute over dogs and trash.

"We tried to talk to the man about his dogs getting in my garbage, and he wasn't there," O'Neill recalled on a recent, windy afternoon. "But when we went back he showed up and when he learned that I had been on his property, he pulled a gun on me and tried to stuff me in the back of his car."

On July 11, a month before the Minnesota mosque bombing, the state's attorney in Ford County, Ill., charged Hari with battery and felony unlawful restraint.

According to the complaint in that case, Hari pushed O'Neill face down into the trunk and held a pellet gun to his head. O'Neill says it was far more serious than police and prosecutors allege; Hari's weapon was no toy.

"I didn't see the gun, but I felt it and it was steel and it was cold, "O'Neill recalled. "And I got two circles on my back from the barrel."