As school referendum campaigns become more costly, is enforcement system up to the task?

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

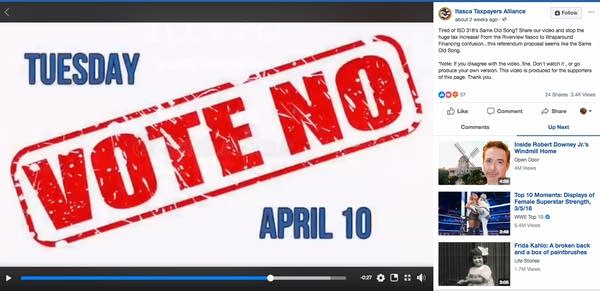

The newspaper insert read "Vote 'NO' April 10th on District 318 bond issue."

The bold, black letters stood out on bright orange paper urging voters to reject the Grand Rapids Public School District's effort to raise money for new elementary schools and upgraded sports facilities.

But it was the smaller type at the bottom of the page that caught Greg Spahn's attention: "Paid for by 'Itasca Taxpayers Alliance.'"

"You can have people throw a lot of money, and a lot of resources at defeating something ... and they can remain anonymous," said Spahn, a Grand Rapids football coach and teacher who worked on a committee trying to pass the district referendum.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Spahn called his opponents "anonymous" because no group called "Itasca Taxpayers Alliance" filed a campaign financial report — the documents that detail donors, contact information and spending for political groups. Reports are required for any organization that spends or raises more than $750 in a calendar year in a local election.

Spahn's complaint is a great example of what a sticky situation local campaign finance can be. It turns out the newspaper insert did top the $750 threshold. Grand Rapids resident and businessperson Anthony Kotula, who placed the ad, said he didn't file a financial report because he paid for the insert with his own money. State law only requires groups to file.

Kotula said he put the line, "Paid for by 'Itasca Taxpayers Alliance,'" at the bottom to drive traffic to the group's Facebook page.

Spending just barely over the limit and rules that are legitimately hard to decipher — it would be easy to dismiss campaign finance in school referendums like this as not worth the worry.

After all, many school referendums attract little or no spending. Most campaign finance advocates have big-money national contests and high-powered lobbyists to occupy their attention.

Still, Minnesota School Boards Association communications director Greg Abbott said increasingly, school tax votes are worth closer scrutiny.

"There are now consultants out there who get paid upwards of $10,000 or more to help "vote no" groups defeat bond referendums," Abbott said.

Abbott said as local businesses leave some communities and tax bases dry up, taxes hit many residents harder. The rise of so-called "vote no" groups means "vote yes" groups spend more to counter.

A school referendum in Worthington this year drew $21,868 spent against the proposal and $5,876 spent to support it. A recent campaign in Minneapolis laid out tens of thousands of dollars in support of that district's referendum.

If campaign finance violations do occur in school district elections, complaints go to the state's Office of Administrative Hearings, which evaluates the case and can issue a penalty or send it to the relevant county attorney. Intentional failure to file required reports is a misdemeanor.

How well that enforcement process works is in dispute. The process puts the burden on someone to report violations. There are no official "campaign finance police" out looking for problems.

"If you pass a law and it has no teeth, then really what good is the law?" Abbott said.

Still, no high profile efforts are underway to change the system. Supporters of the status quo say the enforcement chain provides needed due process.

"There needs to be some type of investigative process," said John Muhar, county attorney for Itasca County, where Grand Rapids is located. "If there's no investigative agency, if there's no process, how does one gather and evaluate that evidence?"

In the end, voters ended up approving the Grand Rapids school district's elementary school proposal and rejected funds for sports facilities.

The Office of Administrative Hearings said as of Wednesday it had not received any campaign complaints about the Grand Rapids referendum. In the past five years, the office has received only a handful of complaints regarding school referendums.