ALS is robbing these Minnesotans of speech, but they won't be silenced

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Judy Bernhardt loves to be involved in the lives of her family, her three daughters and her husband. She likes to be in control, they say. Especially around the kitchen.

So the Duluth resident's firm manner of speaking, her unique voice that is so much a part of her personality, is something the family wanted to preserve after Judy was diagnosed with Lou Gehrig's disease, also called amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or ALS, in November 2017.

Since then the disease has progressed rapidly for the retired nurse, now 64. She can't walk and she relies on an oxygen tank to help her breathe. But her voice is still strong, authoritative.

So recently she's been recording sentences in a small audiology booth at the University of Minnesota Duluth.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Some are practical, like, "Can you help me reposition?"

Others are personal. For her husband: "You're driving me nuts."

And her daughters: "Can I have another glass of wine? Don't tell your dad."

But she's also recording 1,600 sentences pulled from books like "Little Women" and "A Velveteen Rabbit" that will form the backbone of a new synthetic voice, through a process called "voice banking."

"The reason I'm here for the voice banking is to try to preserve my voice, so when I am unable to verbalize that, my family and loved ones can basically hear me speak rather than the synthesis of the voice that sounds like a robot," Bernhardt said.

After Bernhart reads all those sentences, the recordings are sent to a speech research lab at the Nemours/Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children in Wilmington, Del., which developed the voice banking technology about a decade ago.

The sentences are broken down into tiny snippets of speech much smaller than a syllable. Each sound is then indexed by its unique features to basically build a database of each person's voice.

"And then we can use the the linguistic features to locate the specific little snippets of speech that we've stored to reproduce a sentence that sounds natural even though it wasn't one of the sentences that was actually recorded originally," explained Tim Bunnell, who directs the lab.

Talking computers have been in use for several decades, most famously by scientist Stephen Hawking, who had ALS and who died earlier this year. But his voice was robotic sounding.

Experts say it's a critical advancement for people's quality of life to create an artificial voice that sounds much more natural.

"If you don't sound like you, or you don't sound like somebody from your geographic area or your ethnic background or your age, it has an effect on your ability to socialize. There's a part of you that you've lost," said Jolene Hyppa-Martin, a speech-language pathologist at the University of Minnesota Duluth who helped Bernhardt record her voice.

About 50 people have banked their voices across Minnesota since 2016, mostly at the University of Minnesota's Twin Cities and Duluth campuses. The service is also now offered at St. Cloud State University and Minnesota State University Mankato.

Insurance doesn't cover voice banking. The universities do the recordings pro bono. At UMD, Hyppa-Martin donates her time. A nonprofit called Team Gleason pays for the voice synthesis.

"With the way the technology's evolved, people feel like they're getting a piece of their identity back, and that just makes them feel like more of who they are, or who they were before the disease took that from them," said Mike Stephenson, spokesperson for the ALS Association in Minnesota and the Dakotas.

But how realistic does voice banking sound?

Richard Harri of Duluth recently visited Hyppa-Martin to hear his synthesized voice for the first time.

Harri is 67. He uses an oxygen tank to help him breathe, and his voice has gotten weaker.

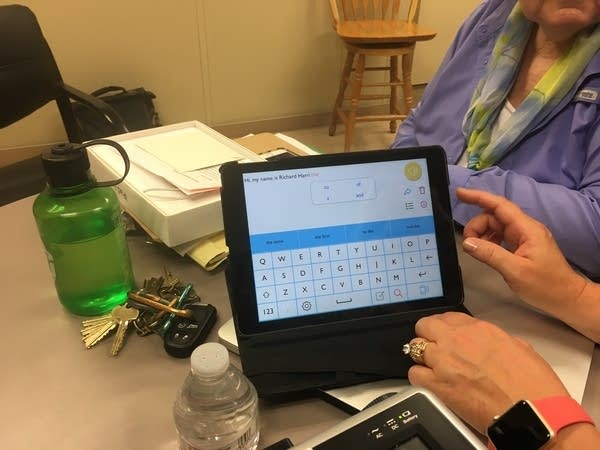

Hyppa-Martin showed him and his wife Peggy an iPad with his synthesized voice loaded onto it. She typed in a message — something that Harri might say to his beloved cat.

"It's time to come to bed, Tuxi."

First, the iPad speaks it. Then Hyppa-Martin asked Harri to say it. And they sound similar, although the iPad version definitely has a computerized quality.

Richard and Peggy Harri are happy with how his new voice sounds. Still, for Peggy Harri, it's bittersweet.

"Yeah it's his [voice], but it's his now," she said. "It isn't his that was. I want him what he was before."

Researchers are developing a way to reconstruct voices using a much smaller sample of old recordings and videos, from before a person got sick.

But right now the technology doesn't sound as natural as voice banking. And of course, what Peggy Harri and others want more than anything is a cure that will make voice banking obsolete.

"I have this love-hate relationship with [voice banking]," said Hyppa-Martin. "I love to work with Rich. And yet I hate voice banking because I never want to have to do it again. I want there to be a cure for ALS."