Dayton's 8 years as governor: sharp elbows, balanced budgets

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

This is the first of a two-part look back at Mark Dayton's life and political career. Part two looked at Dayton's early years, before he made it to the governor's office.

Mark Dayton is trying to figure out what he wants to do with his life.

In January, Dayton and his two German shepherds will move out of their historic home on Summit Avenue in St. Paul and into an apartment in Minneapolis when fellow DFLer Tim Walz takes the oath of office as Minnesota governor.

Dayton, 71, isn't the type to disappear to a warmer climate for months at a time and he laments that he'll probably have to get on social media, like the kids do.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"It's going to be a big shift," he said. "I might have to start tweeting."

Dayton's two terms in office have sometimes been rocky and have taken a toll on his health. But he racked up significant accomplishments during his eight years as governor.

He leaves the state with a projected $1.5 billion budget surplus and more than $2 billion in reserves, a dramatic turnaround from eight years ago, when Minnesota faced a projected $6.2 billion deficit.

He pumped an additional $2 billion into education during his time as governor and guided complex public works projects to fruition, including the Vikings stadium and funding for the Southwest Corridor light rail system.

Dayton signed gay marriage into law. He raised the minimum wage and made good on a campaign promise to raise taxes on the state's top earners. DFL Party activists, who literally shut him out of their 2010 endorsing convention, gave him a standing ovation at this year's gathering.

Dayton tangled with Republicans repeatedly throughout his eight years.

They opposed his tax increases and criticized him for growing state spending. They clashed on substance as well as style, with Republican leaders arguing the governor would change his mind suddenly, or refuse to meet with them, and relations hit rock bottom in 2017 when the Legislature took Dayton to court for eliminating their funding with a veto.

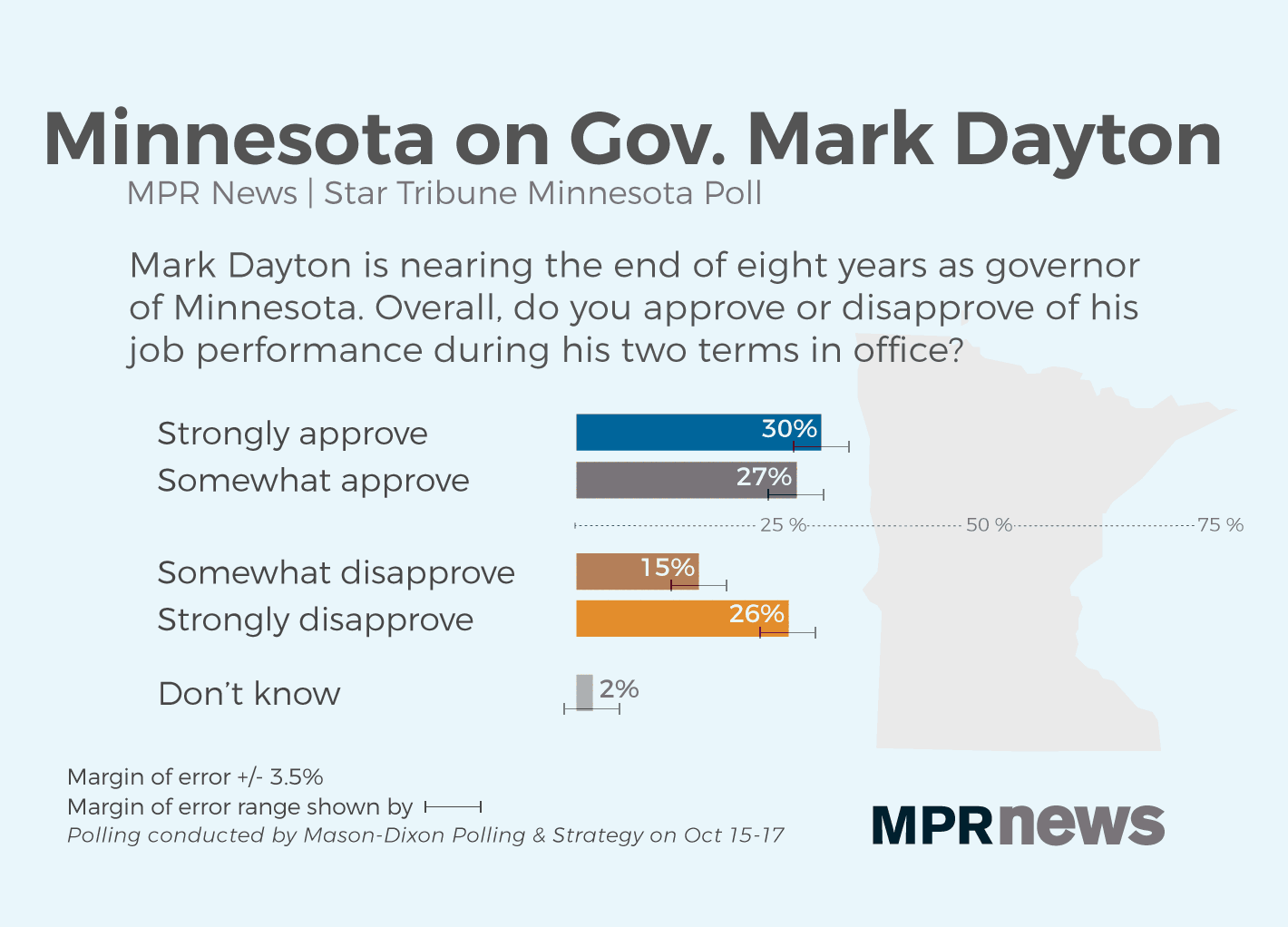

Still, as Dayton leaves office, the latest MPR News/Star Tribune Minnesota poll found 57 percent of Minnesotans say they are satisfied with the job he's done as governor, an above-average approval rating for any politician, even if only 39 percent said they viewed him favorably.

"He is someone who says what he believes, believes what he says," Jeff Blodgett, a longtime DFL organizer, said. "While people don't always agree with him, they like that quality in their leaders and it leads to people trusting him."

The shutdown

Dayton faced his biggest challenge in his first year in office in 2011 — erasing a projected $6.2 billion budget deficit with a Republican-controlled Legislature. The governor insisted the state needed to raise taxes to close the budget gap, but Republicans wanted deeper spending cuts.

Their disagreements stretched well beyond the allotted time for session and eventually led to a government shutdown.

Eventually, Dayton gave in.

He told DFL Party Chair Ken Martin at the time that he needed to fold because thousands of state government workers were out of jobs and there was no movement in sight from Republicans.

Martin, who recognized how politically powerful it would be to bludgeon vulnerable Republicans over the shutdown, urged Dayton to hold out just a bit longer.

Dayton snapped, Martin recalled, and slammed his fists on the table. "He said, 'Gosh darn it, Ken, this is not about scoring political points!'"

At a somber press conference the next day, Republican leaders of the House and Senate flanked Dayton as he announced that he'd dropped his campaign promise to tax the rich, and instead would agree to delay payments to school districts and borrow against future tobacco settlement payments to help close the deficit.

Democrats were disappointed, but Martin says he learned something about Dayton.

"I walked out of there with my tail between my legs," Martin said. "He's not willing to play politics that way."

Some wins, some losses

In 2012, Dayton signed a bill for a new Minnesota Vikings stadium in Minneapolis, after alienating some of his progressive allies to get it passed.

Some criticized him for not pushing harder for the Vikings to pay more and for accepting a deal which left taxpayers footing more than a third of the bill for the $1 billion project.

Judy Cook, a lobbyist who worked on the deal, said his push for the stadium "came from a real genuine understanding that Minnesotans love the Vikings, even if it was a little inconsistent in where you might think he would land on things."

In the next election, Dayton's luck turned around. Democrats regained control of the Legislature. Dayton was able to enact a slew of progressive bills: legalizing gay marriage, raising the minimum wage, and raising income taxes on the state's wealthiest residents, as he promised in his campaign.

Still Dayton often struggled with navigating the 201-member Legislature, even with members of his own party. He famously called a press conference in 2015 to say that Senate Majority Leader Tom Bakk, DFL-Cook, a putative ally, had "stabbed me in the back" when he suspended pay raises approved by Dayton for the top members of his administration.

"I'm not sure how much he liked dealing with other lawmakers," said Bill Blazar, who's known Dayton since the 1980s and worked for the Minnesota Chamber of Commerce during Dayton's time as governor.

"He is very difficult to work with. I'll point to the fact in this last session, we just bent over backward to get bills into the shape that he wanted," House Speaker Kurt Daudt, R-Zimmerman, told MPR News last month.

"In the last week of session, he canceled meetings with us, or refused to meet with us, six times in seven days," Daudt said. "To me, that's just not Minnesotan."

Regrets

Dayton anguishes over two areas where he feels his administration provided bad customer service to Minnesotans: the MNsure health insurance exchange website and the MNLARS system for vehicle registration. Both became yearslong debacles.

Reflecting on his biggest regrets, Dayton says he wished both would have been rolled out differently.

"I believe in good government and I believe in government providing quality service to people in a tax-efficient way, and both of those fell short of that standard," Dayton said.

He also knew part of the job of governor was to sell his ideas to constituents, and he regrets that he couldn't sell Minnesotans on his push to clean up lakes and streams that have been polluted by agricultural runoff. His attempts to create buffers between farmland and waterways were met with a huge backlash.

"I thought if I dramatized it as an issue, people would rise up and say 'we're not going to stand for this. We want our water to be clean, we insist on it,'" Dayton said. "I wasn't able to mobilize the public to see their legitimate self-interest."

As state improved, Dayton deteriorated

In 2017, more than three-quarters of the way through his annual State of the State Address, Dayton paused to take a drink of water.

His words slurred and his head slowly slumped down. It banged once loudly on the House Speaker's rostrum before he collapsed.

He was taken home to recover that evening, but at a press conference the next day, he casually disclosed that he'd been diagnosed with prostate cancer.

It was a startling series of events, but not exactly surprising. Dayton was dogged by back and leg pain. As the years went on, he used a cane to keep his balance. His family worried he poured too much of himself into his job, sometimes at the expense of his own health.

Dayton underwent two spinal surgeries during his early years as governor, but the pain persisted. In October of 2018, he had two more surgeries at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn.

There were complications, which Dayton hasn't described in much detail, and the outcome was dire. He was in the intensive care unit with his kidneys failing and his lungs filling up with liquid. He ended up spending more than 40 days at Mayo, "wired to an oxygen tank," he said.

Dayton had intended to travel the state in his final weeks in office. Instead, he returned to St. Paul just before Thanksgiving and has barely appeared in public since. While frustrated by his health, he's still able to dispatch the situation with a self-deprecating joke.

"When I took office, I was the oldest person to ever become governor in Minnesota, and the previous oldest person died in office," Dayton said. "I'm four weeks away from surpassing that."

Legacy

Sitting at the end of a long, wood dining room table in the governor's residence recently, Dayton was more comfortable talking about his regrets than what he considers his accomplishments as governor.

When pressed, he cites his successful push to increase funding for public education every year he was governor and the passage of all-day kindergarten. He said he's excited to see the University of Minnesota medical school become a top research institution once again, after an infusion of state dollars.

He signed billions of dollars of public infrastructure projects, and he's proud of the jobs that were created and the businesses that came to Minnesota or expanded while he was governor. And he's quick to mention the financial situation of the state, though surpluses and budget reserves are largely unseen by the public.

In fact, he doesn't expect the public to dwell on most of what he's done as governor.

"I don't think people spend a lot of time thinking about governors' legacies," Dayton said. "You don't do it for the political or life obituaries you're going to get or not get. I hope people can come to see a lot of what I did was driven by what I believed was right for Minnesota."