The unlikely contributor to Minn.'s greenhouse gas emissions: Your favorite lake

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Minnesota's lakes have always released greenhouse gases. But scientists have only recently realized just how significant those carbon dioxide and methane emissions are.

A close look at the state's most recent report on the sources of greenhouse gas emissions reveals a new category: Inland waters, like lakes and streams and rivers and wetlands. And because emissions in that category mostly come from methane — a greenhouse gas much more potent than carbon dioxide — they add up fast.

According to the state's calculations, Minnesota's inland waters release about the same amount of greenhouse gases as burning natural gas to heat Minnesota homes and the coal-fired power Minnesota imports from the Dakotas.

John Downing, who directs the Minnesota Sea Grant program, is among the scientists who have been working to better understand emissions from lakes — and their impact.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"We found, in fact, lakes are really big sources of [greenhouse gases] to the atmosphere worldwide. That surprised a lot of people," he said.

Knowing more about lakes' greenhouse gas emissions gives scientists a much more realistic view of where greenhouse gases are coming from — and which sources we can most easily control in our efforts to combat climate change.

How do lakes release greenhouse gases?

Lakes release greenhouse gases largely thanks to decomposing algae and other organisms.

At the end of their life cycle, the organisms sink to the bottom of the lake. As that organic material decomposes, it naturally increases the amount of carbon in a lake's sediment.

Some of that carbon turns into carbon dioxide and methane gas. Those gases are diffused into the atmosphere by bubbling up toward the surface of the lake, and releasing the gas when they pop.

If you've ever seen bubbles come up from the bottom of a lake, those are likely methane bubbles.

Have humans had anything to do with how much greenhouse gas emissions are coming from lakes?

Yes. It's true that lakes have always cycled carbon and released greenhouse gases, but two things influence how much of those gases they're releasing now.

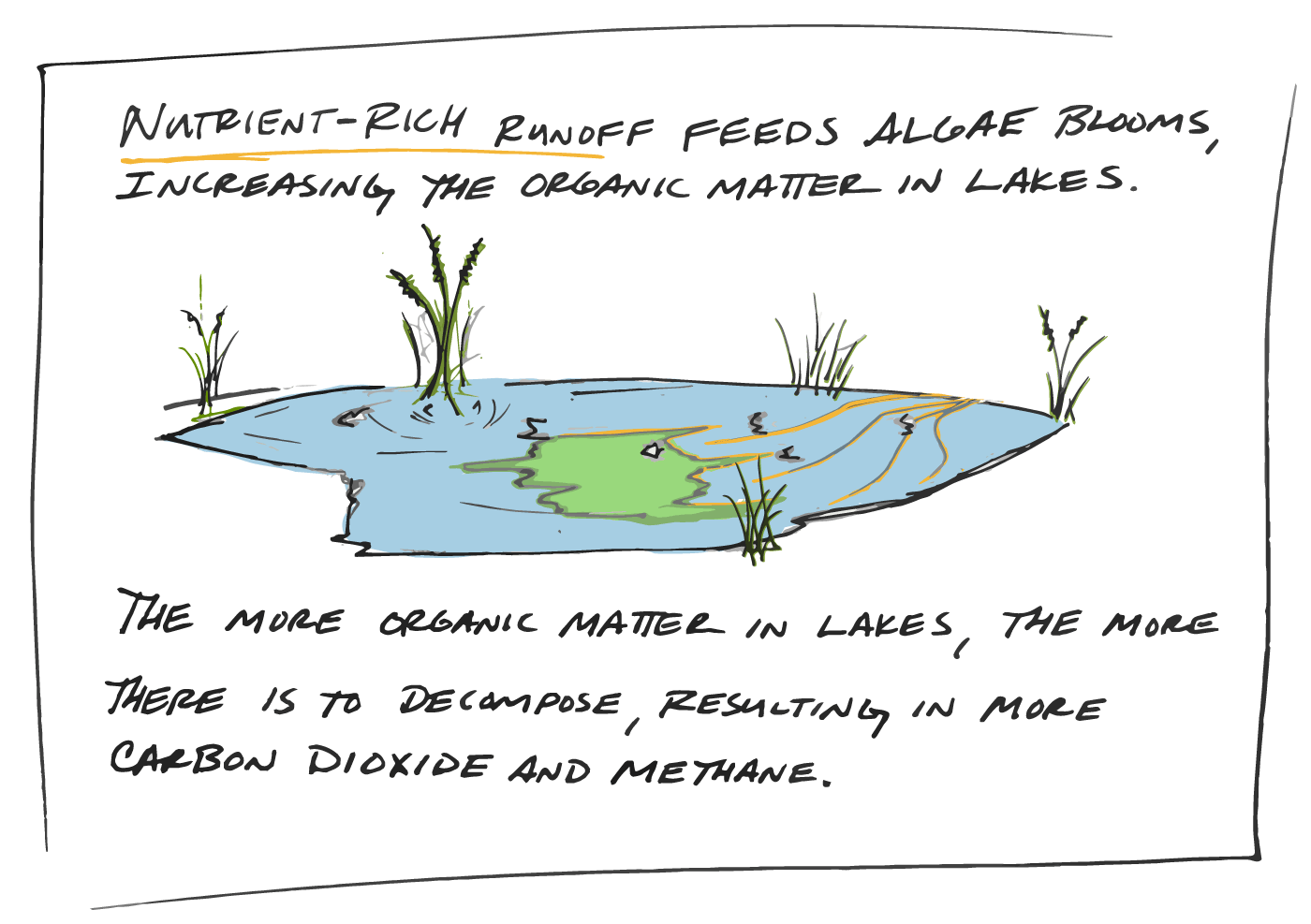

One of those factors is land use. As cities and farms expand, they create more opportunities for runoff.

Increased runoff from cities and farmland tends to make lakes greener, because it gives algae more nutrients to feed on. And that kicks off the cycle of algae growth to decomposition that leads to gases coming off the surface of the lakes.

The other factor that affects algae growth in a lake is temperature. Higher temperatures speed up algae reproduction. And the more algae on a lake, the more greenhouse gas emissions come from the lake. The warming trend happening across the globe can be traced back to the burning of fossil fuels, which release gases that trap more of the sun's heat in the atmosphere.

"Unless we keep lakes from getting greener, the actual effect of lakes and ponds on greenhouse gas emissions will increase," Downing said.

"It just gives us another reason, other than recreation and good drinking water and stuff like that to protect water quality in our surface waters because it can also affect the climate."

How do scientists know how much carbon dioxide and methane are being released from lakes in Minnesota?

Scientists estimate greenhouse gas emissions based on lakes' and ponds' surface area. They pair those calculations with data on emissions from lakes with similar characteristics and come up with an estimate for how much gas Minnesota's lakes are emitting.

Traditionally, scientists have estimated lakes' emissions by taking a water sample, then determining the amount of carbon dioxide in the sample through a series of calculations involving things like temperature, acidity and alkalinity, said Adam Heathcote, who studies lakes at the Science Museum of Minnesota's St. Croix Watershed Research Station.

But the latest scientific instruments, Heathcote said, make it possible for scientists to conduct real-time, continuous measurements of lake emissions.

The problem is that those instruments are expensive and can't be deployed on every lake everywhere. So scientists combine what they know about the methane and carbon dioxide coming off lakes with other lake data, such as size and location, of individual lakes. Then they combine that information to reach a global estimate.

"When you add up the entire area of lakes in the world, it's not insignificant," Heathcote said.

How has scientists' understanding of lake emissions evolved?

Scientists used to think lakes were part of a closed system in which carbon was deposited in lake beds and then eventually moved into underground aquifers, streams and rivers — and then on to the oceans.

"Inland waters were treated as what we might call a neutral pipe," Downing said. "Then we started doing the calculations. We figured out that it's an active pipe — a pipe that's leaky for carbon and methane."

And because that's a fairly new development in scientists' understanding of water bodies, Heathcote said that even at scientific conferences, he often has to explain the latest science on lakes' roles in the carbon cycle.

Now that the cycle is better understood, it's showing up in big reports that detail all the significant sources of greenhouse gases on the planet. That includes the most recent reports from the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and this year's greenhouse gas inventory for Minnesota.