Across Minnesota, diversion projects drain the fear from flood season

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

This was the first spring in almost 20 years that Roseau Mayor Jeff Pelowski didn't have to think about sandbags.

"I wanted to know where they were," he said. "Just in case."

But those stockpiles were really just a precaution, because Roseau recently finished a $46 million flood diversion system. Pelowski described it as a 4-mile backup riverbed, designed to reroute floodwaters around the city.

The project wasn't tested by an actual flood until this spring, but Pelowski said he never doubted it.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"We didn't have any intention of sandbagging," he said.

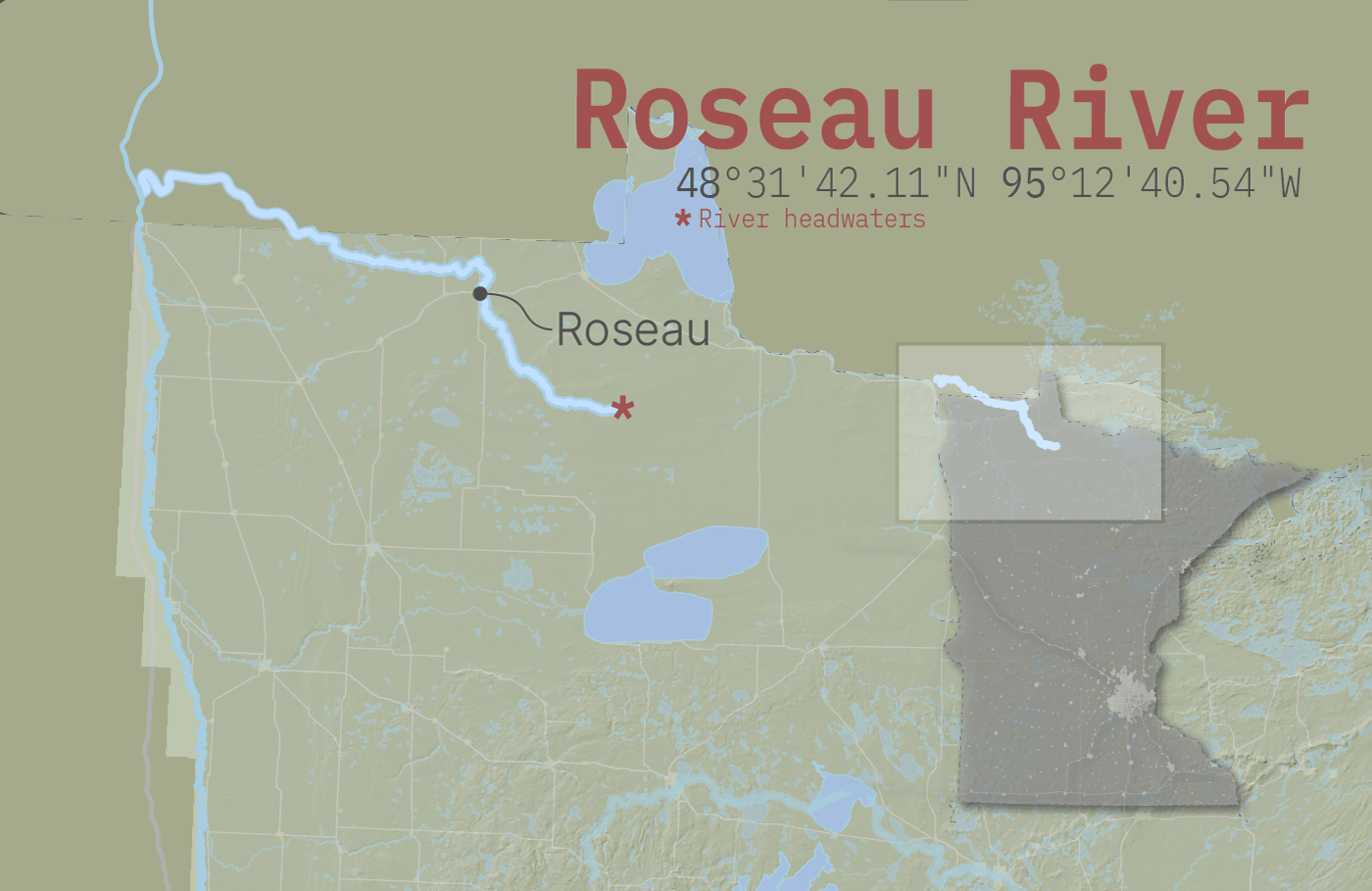

Roseau is just like a lot of historically flood-prone towns and cities in Minnesota. It sits on the banks of a shallow river — the Roseau River — in a place where elevation and topography leave the city especially vulnerable to flooding.

Like many other communities, sandbagging had become an exhausting and terrifying springtime ritual. And just like those other communities, that ritual is becoming a thing of the past.

Pat Lynch, who coordinates flood infrastructure projects for the Minnesota Department of Natural Resources, said his work tends to fly under the radar.

"It's not real newsworthy when a town that used to flood doesn't flood," he said. "It's not real sexy."

He laid out a list of Minnesota cities, like Roseau, that used to flood all the time and are finally protected:

• The small city of Ada, Minn., northeast of Moorhead, was a disaster zone in the historic 1997 floods. It completed a ring dike last year and easily weathered this year's flood season.

• The city of Afton, along the St. Croix River southeast of the Twin Cities, just finished a levee replacement project.

• The city of Crookston, on the Red Lake River in northwestern Minnesota, recently built up its levee system so much that this year's flood crest of just under 25 feet didn't even raise an eyebrow.

• The small city of Oslo, north of Grand Forks along the Red River, was cut off for a few weeks. That's actually pretty common for Oslo. It has been cut off five times in the last 10 years. This year it was especially well prepared, with a recently improved levee system.

All that flood mitigation has cost a lot of state, local and federal money. In the last decade, the state alone spent roughly $500 million on flood projects, according to Lynch. More came in from local communities and the federal government. It was a battle to get that funding, Lynch said. And it took a very long time.

Many of these new levees and diversions were prompted by huge floods in 1997 and 2009, but were completed only recently.

Roseau's new diversion was among them.

The city has flooded a few times, but the worst in recent memory happened in the summer of 2002, early into Pelowski's tenure as mayor. Twenty inches of rain fell in two days, swelling the Roseau River and flooding the city.

About half of Roseau's population was inundated. Pelowski's house was, too. Then, when the city's water treatment system failed, the rest of Roseau got 5 feet of raw sewage in their basements. Nearly the entire city had to evacuate.

For the next 15 years, Pelowski and Roseau's community development coordinator, Todd Peterson, worked with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build their flood diversion system.

They thought it would be done in just a few years, but Peterson said getting the funding turned out to be incredibly complex.

"Congressional authorizations, congressional appropriations," he said. "Just haggling over funding. That slowed things down."

They had to build the diversion a little at a time, while begging federal and state lawmakers for cash.

Pelowski said he spent every spring worrying that his city would flood again. And there were some close calls: in 2004, 2006 and again in 2009.

"People got pretty sick of sandbagging," he said.

The project was finally finished in 2016. Last year, FEMA gave the diversion its final approval: removing Roseau from the 100-year floodplain.

At the start of this year's spring flood season, Pelowski and Peterson drove the muddy dirt roads along the edge of their new diversion. They parked 100 yards from the eastern levee and hiked the rest of the way. They squinted out over the land.

The Roseau diversion is basically just a very wide, shallow ditch, looping around the eastern side of the city. There are cattails at the bottom. It's not especially impressive, from a visual standpoint.

"When I stand up here," Peterson said, "it looks like we didn't do anything at all."

Pelowski nodded. "It looks like a field," he said.

Maybe it doesn't look like much, but that $46 million ditch meant that Roseau didn't flood this year. The Roseau River crested just high enough to send water into the diversion for the very first time.

It wasn't much water — it was a trickle, really. But if the diversion hadn't been there to catch it, Peterson said a few neighborhoods would have had to sandbag, and nobody wanted to do that.